Scientists risk overestimating numbers of wild bonobos

Study warns that changing climate in the Congo Basin is impacting assessment of the endangered apes

2021-07-01

(Press-News.org) There might be fewer bonobos left in the wild than we thought. For the last 40 years, scientists have estimated the abundance of endangered bonobos by counting the numbers of sleeping nests left by the apes in forests of the Congo Basin. Now, researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior report that the rate of sleeping nest "decay" has lengthened by 17 days over the last 15 years as a result of declining rainfall in the Congo Basin. The study warns that longer nest decay times have serious implications for ape conservation: failure to account for these changes would lead to overestimating population density by up to 60 percent, subsequently jeopardizing conservation of these endangered great apes in the wild.

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are a species of great ape similar to chimpanzees that are found only in the rainforests of the Congo Basin--the second largest forest area of the planet and known as one of Earth's "green lungs."

The study of the LuiKotale Bonobo Project, which is part of an ongoing collaboration with scientists at Liverpool John Moores University, the Centre for Research and Conservation, and the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, aimed to assess the influence of weather on the decomposition of bonobo sleeping platforms, also called nests. In the LuiKotale research site in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the scientists studied 15 years of climate data, including rainfall, and 1,511 bonobo nests observed from construction to disappearance. "While climate change is known to be impacting Central African rainforests, a lack of real data from the Congo Basin meant that we didn't know how this was affecting the region and bonobos," says Barbara Fruth, Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Konstanz, Germany, who is senior author on the study. "Our study provides evidence that the world's largest freshwater reservoir is suffering from climate change," she says.

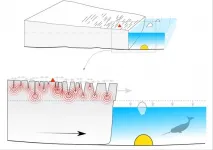

How to convert nest counts into ape counts

This troubling trend has added importance for bonobos, and great apes in general, because their populations are estimated not by counting actual apes, but rather the nests left by the primates each night. Knowing how fast these nests disappear is essential for converting nest counts to ape counts. The study's results showed a steady decline of rainfall across years and the impact of this on bonobo nest decay times. Less rain meant that nests persisted for longer in the forest. Further, the scientists observed bonobos using more solid construction types in response to more unpredictable storms.

The connection between nest decay and climate change is relevant to conservation of all great apes because nest counts are used as the "gold standard for estimating their populations," says first author Mattia Bessone, a PhD student at Liverpool John Moores University who is working on validating cutting-edge methods for assessing threatened species. "As climate change continues to affect both the process of nest decay and ape nest building behaviour, great ape nest decomposition times are likely only to increase further in future years. "We stress the absolute necessity to take into account the specific impact of climate on nests in areas where these are being used to surveying great apes. Failure to do so will invalidate biomonitoring estimates of global significance and subsequently jeopardize the conservation of great apes in the wild."

INFORMATION:

Original publication

Mattia Bessone, Lambert Booto, Antonio R. Santos, Hjalmar S. Kühl, Barbara Fruth

No time to rest: how the effects of climate change on nest decay threaten the conservation of apes in the wild

PLOS ONE

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-01

DALLAS - June 30, 2021 - A relative decline in wealth during midlife increases the likelihood of a cardiac event or heart disease after age 65 while an increase in wealth between ages 50 and 64 is associated with lower cardiovascular risk, according to a new END ...

2021-07-01

The cells that make up our bodies are constantly exposed to a wide variety of mechanical stresses. For example, the heart and lungs have to withstand lifelong expansion and contraction, our skin has to be as resistant to tearing as possible whilst retaining its elasticity, and immune cells are very squashy so that they can move through the body. Special protein structures, known as "intermediate filaments", play an important role in these characteristics. Researchers at Göttingen University have now succeeded for the first time in precisely measuring which physical effects determine the properties of the individual filaments, and which specific features only occur through the interaction ...

2021-07-01

Melbourne researchers have found that liquid chalk, commonly used in gyms to improve grip, acts as an antiseptic against highly infectious human viruses, completely killing both SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) and influenza A viruses.

University of Melbourne Professor Jason Mackenzie, a laboratory head at the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) wanted to investigate whether liquid chalk stopped SARS-CoV-2 transmission after conversations with his daughter - an elite rock climber heading to the Tokyo Olympics.

"Both of my daughters were lamenting the closure of gyms at the beginning of the pandemic, particularly my daughter Oceania who was trying to train ...

2021-07-01

There are certain rules that even the most extreme objects in the universe must obey. A central law for black holes predicts that the area of their event horizons -- the boundary beyond which nothing can ever escape -- should never shrink. This law is Hawking's area theorem, named after physicist Stephen Hawking, who derived the theorem in 1971.

Fifty years later, physicists at MIT and elsewhere have now confirmed Hawking's area theorem for the first time, using observations of gravitational waves. Their results appear in Physical Review Letters.

In the study, the researchers take a closer look at GW150914, ...

2021-07-01

Exercise training can help support management of overweight and obesity in adults, and can contribute to health benefits beyond "scale victories". The supplement published today in Obesity Reviews, based on the work of an expert group convened under the auspices of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), provides scientific evidence on health and wellbeing benefits of exercise training for people living with overweight and obesity. Supplement highlights include a summary of key recommendations; additional developed materials provide infographic tools for health care practitioners (HCPs) and people ...

2021-07-01

Economists at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, economists found passers-by often donated more when paying via a digital platforms like apps, QR codes, PayPal and even Bitcoin, compared to the centuries' old payment method of loose coins.

Using data from the online platform The Busking Project, the study analysed individual payments to over three and half thousand active buskers from 121 countries to predict the characteristics of performers who were more likely to receive online donations.

The study found North America and Europe were home to the most active buskers and audiences on the platform, with buskers registered ...

2021-07-01

Scientists show that an ocean-bottom seismometer deployed close to the calving front of a glacier in Greenland can detect continuous seismic radiation from a glacier sliding, reminiscent of a slow earthquake.

Basal slip of marine-terminating glaciers controls how fast they discharge ice into the ocean. However, to directly observe such basal motion and determine what controls it is challenging: the calving-front environment is one of the most difficult-to-access environments and seismically noisy -- especially on the glacier surface -- due to heavily crevassed ice and harsh weather conditions.

A team of scientists from Hokkaido University, ...

2021-07-01

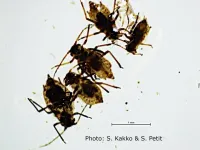

An invasive species of aphid could put some threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island at risk as researchers from the University of South Australia confirm Australia's first sighting of Aphis lugentis on the Island's Dudley Peninsula.

It is another blow for Kangaroo Island's environment, especially following the Black Summer bushfires that decimated more than half the island and 96 per cent of Flinders Chase National Park.

Collected by wildlife ecologist Associate Professor Topa Petit and identified by colleagues from the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, the black aphids were found feeding on seedlings of Senecio odoratus, a native species of daisy, commonly known as the scented groundsel.

Of ...

2021-07-01

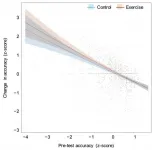

Over the past 20 years, many studies have investigated the effects of acute aerobic exercise on cognitive performance. In recent years, meta-analyses*1 of data from these previous research studies have demonstrated that these a single bout of moderate aerobic exercise temporarily improves cognitive performance. However, close examination of the individual research studies on this topic revealed that in approximately 50% of studies, no beneficial link between acute aerobic exercise and cognitive function was found.

An international research collaboration, including Associate ...

2021-07-01

Ibaraki, Japan - Flowers come in a multitude of shapes and colors. Now, an international research team led by a researcher from Japan has proposed the novel hypothesis that trade-offs caused by different visitors may play an important role in shaping this floral diversity.

In a study published last month, the team explored how the close associations between flowers and the animals that visit them influence flower evolution.

Visitors to flowers may be beneficial, like pollinators, or detrimental, like pollen thieves. All of these visitors interact with flowers in different ways and exert different selection pressures on flower traits such as color and scent. For example, a scent that attracts one pollinator may deter other potential pollinators. In this case, the flower would be expected ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists risk overestimating numbers of wild bonobos

Study warns that changing climate in the Congo Basin is impacting assessment of the endangered apes