(Press-News.org) Scientists have long searched in vain for a class of brain cells that could explain the visceral flash of recognition that we feel when we see a very familiar face, like that of our grandmothers. But the proposed "grandmother neuron"--a single cell at the crossroads of sensory perception and memory, capable of prioritizing an important face over the rabble--remained elusive.

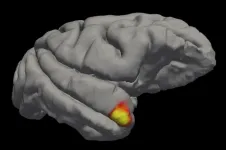

Now, new research reveals a class of neurons in the brain's temporal pole region that links face perception to long-term memory. It's not quite the apocryphal grandmother neuron--rather than a single cell, it's a population of cells that collectively remembers grandma's face. The findings, published in Science, are the first to explain how our brains inculcate the faces of those we hold dear.

"When I was coming up in neuroscience, if you wanted to ridicule someone's argument you would dismiss it as 'just another grandmother neuron'--a hypothetical that could not exist," says Winrich Freiwald, professor of neurosciences and behavior at The Rockefeller University.

"Now, in an obscure and understudied corner of the brain, we have found the closest thing to a grandmother neuron: cells capable of linking face perception to memory."

Have I seen that face before?

The idea of a grandmother neuron first showed up in the 1960s as a theoretical brain cell that would code for a specific, complex concept, all by itself. One neuron for the memory of one's grandmother, another to recall one's mother, and so on. At its heart, the notion of a one-to-one ratio between brain cells and objects or concepts was an attempt to tackle the mystery of how the brain combines what we see with our long-term memories.

Scientists have since discovered plenty of sensory neurons that specialize in processing facial information, and as many memory cells dedicated to storing data from personal encounters. But a grandmother neuron--or even a hybrid cell capable of linking vision to memory--never emerged. "The expectation is that we would have had this down by now," Freiwald says. "Far from it! We had no clear knowledge of where and how the brain processes familiar faces."

Recently, Freiwald and colleagues discovered that a small area in the brain's temporal pole region may be involved in facial recognition. So the team used functional magnetic resonance imaging as a guide to zoom in on the TP regions of two rhesus monkeys, and recorded the electrical signals of TP neurons as the macaques watched images of familiar faces (which they had seen in-person) and unfamiliar faces that they had only seen virtually, on a screen.

The team found that neurons in the TP region were highly selective, responding to faces that the subjects had seen before more strongly than unfamiliar ones. And the neurons were fast--discriminating between known and unknown faces immediately upon processing the image.

Interestingly, these cells responded threefold more strongly to familiar over unfamiliar faces even though the subjects had in fact seen the unfamiliar faces many times virtually, on screens. "This may point to the importance of knowing someone in person," says neuroscientist Sofia Landi, first author on the paper. "Given the tendency nowadays to go virtual, it is important to note that faces that we have seen on a screen may not evoke the same neuronal activity as faces that we meet in-person."

A tapestry of grandmothers

The findings constitute the first evidence of a hybrid brain cell, not unlike the fabled grandmother neuron. The cells of the TP region behave like sensory cells, with reliable and fast responses to visual stimuli. But they also act like memory cells which respond only to stimuli that the brain has seen before--in this case, familiar individuals--reflecting a change in the brain as a result of past encounters. "They're these very visual, very sensory cells--but like memory cells," Freiwald says. "We have discovered a connection between the sensory and memory domains."

But the cells are not, strictly speaking, grandmother neurons. Instead of one cell coding for a single familiar face, the cells of the TP region appear to work in concert, as a collective.

"It's a 'grandmother face area' of the brain," Freiwald says.

The discovery of the TP region at the heart of facial recognition means that researchers can soon start investigating how those cells encode familiar faces. "We can now ask how this region is connected to the other parts of the brain and what happens when a new face appears," Freiwald asks. "And of course, we can begin exploring how it works in the human brain."

In the future, the findings may also have clinical implications for people suffering from prosopagnosia, or face blindness, a socially isolating condition that affects about one percent of the population. "Face-blind people often suffer from depression. It can be debilitating, because in the worst cases they cannot even recognize close relatives," Freiwald says.

"This discovery could one day help us devise strategies to help them."

INFORMATION:

The COVID-19 catastrophe in India has resulted in more than 30 million people infected with the virus and nearly 400,000 deaths, though experts are concerned that the figures most likely are much higher. Meanwhile, another public health crisis has emerged along with COVID-19: the widespread misuse of antibiotics.

During India's first surge of COVID-19, antibiotic sales soared, suggesting the drugs were used to treat mild and moderate cases of COVID-19, according to research led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Such use is considered inappropriate because antibiotics are only effective against bacterial infections, not viral infections such as COVID-19, and overuse increases the risk ...

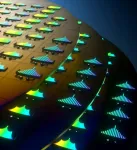

Fifteen years ago, UC Santa Barbara electrical and materials professor John Bowers pioneered a method for integrating a laser onto a silicon wafer. The technology has since been widely deployed in combination with other silicon photonics devices to replace the copper-wire interconnects that formerly linked servers at data centers, dramatically increasing energy efficiency -- an important endeavor at a time when data traffic is growing by roughly 25% per year.

For several years, the Bowers group has collaborated with the group of Tobias J. Kippenberg at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL), within the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Direct On-Chip Digital Optical ...

Optical frequency combs consist of light frequencies made of equidistant laser lines. They have already revolutionized the fields of frequency metrology, timing and spectroscopy. The discovery of ''soliton microcombs'' by Professor Tobias Kippenberg's lab at EPFL in the past decade has enabled frequency combs to be generated on chip. In this scheme, a single-frequency laser is converted into ultra-short pulses called dissipative Kerr solitons.

Soliton microcombs are chip-scale frequency combs that are compact, consume low power, and exhibit broad bandwidth. Combined with large spacing of comb "teeth", microcombs are uniquely ...

Conversations between seriously ill people, their families and palliative care specialists lead to better quality-of-life. Understanding what happens during these conversations - and particularly how they vary by cultural, clinical, and situational contexts - is essential to guide healthcare communication improvement efforts. To gain true understanding, new methods to study conversations in large, inclusive, and multi-site epidemiological studies are required. A new computer model offers an automated and valid tool for such large-scale scientific analyses.

Research results on this model were published today in PLOS ONE.

Developed by a team of computer scientists, clinicians and engineers at the University of Vermont, the approach - called CODYM ...

A study by Stanford University School of Medicine investigators hints that people with COVID-19 may experience milder symptoms if certain cells of their immune systems "remember" previous encounters with seasonal coronaviruses -- the ones that cause about a quarter of the common colds kids get.

These immune cells are better equipped to mobilize quickly against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19, if they've already met its gentler cousins, the scientists concluded.

The findings may help explain why some people, particularly children, seem much more resilient than others to infection by SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. They also might make it possible ...

Scientists have developed a new technology to detect a wider variety of T cells that recognize coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2. The technology revealed that killer T cells capable of recognizing epitopes conserved across all coronaviruses are much more abundant in COVID-19 patients with mild disease versus those with more severe illness, suggesting a protective role for these broad-affinity T cells. The ability to distinguish T cells based on their affinities to SARS-CoV-2 could help scientists elucidate the disparity in COVID-19 outcomes and determine which COVID-19 patients will or will not exhibit a successful immune response ...

In a new Editorial, Peter Heeger, Christian Larsen, and Dorry Segev discuss recent evidence - including a recent Science Immunology study by Hector Rincon-Arevalo and colleagues - that points to a diminished immune response to COVID-19 vaccines among organ transplant recipients and others on immunosuppressive drug regimens. The authors note that this presents challenges at both the individual and population levels, since current vaccine protocols may not provide adequate protection to immunosuppressed patients - who could, in turn, become reservoirs for new and dangerous variants of the virus. As such, Heeger, Larsen, and Segev argue that developing vaccination strategies for transplant recipients should be a high priority in the next wave of research focused on fighting COVID-19. ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Research by investigators at Mayo Clinic Cancer Center suggests that physicians should screen patients with lung cancer for MET amplification/overexpression before determining a treatment strategy. Their findings are published Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"In our research we found several lung cancer cases that were not responsive to standard chemotherapy," says Zhenkun Lou, Ph.D., a cancer researcher at Mayo Clinic. "Because these lung cancers were positive for PD-L1, a protein that allows some cells ...

A key factor in America's prodigious agricultural output turns out to be something farmers can do little to control: clean air. A new Stanford-led study estimates pollution reductions between 1999 and 2019 contributed to about 20 percent of the increase in corn and soybean yield gains during that period - an amount worth about $5 billion per year.

The analysis, published this week in Environmental Research Letters, reveals that four key air pollutants are particularly damaging to crops, and accounted for an average loss of about 5 percent of corn and soybean production over the study period. The findings could help inform technology and policy changes to benefit American agriculture, and underscore the ...

The number of people who live past the age of 100 has been on the rise for decades, up to nearly half a million people worldwide.

There are, however, far fewer "supercentenarians," people who live to age 110 or even longer. The oldest living person, Jeanne Calment of France, was 122 when she died in 1997; currently, the world's oldest person is 118-year-old Kane Tanaka of Japan.

Such extreme longevity, according to new research by the University of Washington, likely will continue to rise slowly by the end of this century, and estimates show that a lifespan of 125 years, or even 130 years, is possible.

"People are fascinated by the extremes of humanity, whether it's going to the moon, how fast someone can run in the Olympics, or even how long someone ...