(Press-News.org) As tectonic plates slip past each other, the rivers that cross fault lines change shape. The shifting ground stretches the river channels until the water breaks its course and flows onto new paths.

In a study published July 9 in Science, researchers at UC Santa Cruz created a model that helps predict this process. It provides broad context to how rivers and faults interact to shape the nearby topography.

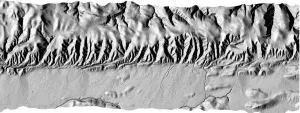

The group originally planned to use the San Andreas fault in the Carrizo Plain of California to study how fault movement shapes the landscapes near rivers. But after spending hours pouring over aerial imagery and remote topographic data, their understanding of how the terrain evolves began to change. They realized that rivers play a more active role in shaping the area than once thought.

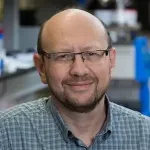

"The rivers are their own little beasts, and they interact in really interesting ways with the kinematics and the motion along these faults," said Kelian Dascher-Cousineau, seismology Ph.D. student at UC Santa Cruz and lead author on the study.

As the offset of a fault grows, it elongates river channels and slows the flow of water. With lower speeds, the river carries less sediment. The material builds up and eventually blocks the path, forcing the water to change course in a process known as avulsion.

This diversion happens rapidly, and the unexpected flooding can easily become destructive for nearby communities.

Over the last few years, geomorphologists have gained a clearer idea of how these avulsions happen in different types of rivers. But identifying long-term patterns in the way that rivers respond to fault movement still proves challenging.

"You can't really observe channels for thousands of years at a time," said Dascher-Cousineau. To make up for that inability, the researchers used the well-studied past of the San Andreas Fault at the Carrizo Plain to test their model.

"We have a history that we actually know really well from the earthquakes, and we can use that as a natural experiment to see what the channels are doing over these geomorphologically relevant timescales," said Dascher-Cousineau.

The group closely examined images and maps of the Carrizo Plain and began testing complex models of river flow and sediment transport. They slowly removed variables, eventually identifying the most important elements in the system. The resulting model introduces a new framework for thinking about how rivers and active fault-lines interact.

"Most seismologists typically have a view that the surface of the Earth is a passive thing that just responds to the faulting," said Noah Finnegan, professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz and co-author on the study.

"This paper embraced the fact that rivers are constantly changing and was able to show that the coevolution of the fault-offset and the river provides us with information that we weren't able to get previously," he said. "You get a richer understanding of how the system works by recognizing that there's an interesting coupling going on there."

In addition to predicting when fault-crossing rivers will abandon their original channels, the model can also help scientists estimate how quickly the sides of a fault are moving past one another--an important question to many seismologists that can be difficult to measure accurately.

"If you know something about how the river works, you can get quantitative constraints on the rate of slip on the fault, which is something that is a common goal of studies of faults," said Finnegan. "Alternatively, if you know something about the rate at which the fault is slipping, you can learn something about how efficient the river is at moving sediment, which is a basic question in almost every study of rivers and is almost impossible to know in a really accurate way."

Although it addresses complex questions, the model itself is surprisingly straightforward.

"Like with a lot of discoveries, once you see it in the right way, there's incredible simplicity," said Finnegan. "I'll never look at these landscapes in the same way again."

The group created the model while working entirely virtually--a challenge that Finnegan said inspired creativity.

"We were forced to look at remote topographic data and aerial imagery that made us think in a more synoptic way about this," he said.

How the model will fit different regions and the fault at a larger scale remains to be seen.

"We've outlined the set of physics that should operate in one range of conditions," said Dascher-Cousineau. Next, they will turn their focus to new types of topography.

INFORMATION:

Emily Brodsky, professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UCSC, is also a coauthor of the paper, in addition to Dascher-Cousineau and Finnegan. This research was supported by the NASA FINESST fellowship and the Southern California Earthquake Center.

For the first time, Princess Margaret researchers have mapped out where and how leukemia begins and develops in infants with Down syndrome in preclinical models, paving the way to potentially prevent this cancer in the future.

Children with Down syndrome have a 150-fold increased risk of developing myeloid leukemia within the first five years of their life. Yet the mechanism by which the extra copy of chromosome 21 predisposes to leukemia remains unclear.

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by a random error in cell division in early human development that results in an extra copy of chromosome 21. This extra copy is what causes the developmental changes and physical ...

Proactive, frequent rapid testing of all students for COVID-19 is more effective at preventing large transmission clusters in schools than measures that are only initiated when someone develops symptoms and then tests positive, Simon Fraser University researchers have found. Professors Caroline Colijn and Paul Tupper used a mathematical model to simulate COVID-19's spread in the classroom and published their research results today in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

The simulations showed that, in a classroom with 25 students, anywhere from zero to 20 students might be infected after exposure, depending on even small adjustments ...

(BOSTON) -- Current clinical interventions for infectious diseases are facing increasing challenges due to the ever-rising number of drug-resistant microbial infections, epidemic outbreaks of pathogenic bacteria, and the continued possibility of new biothreats that might emerge in the future. Effective vaccines could act as a bulwark to prevent many bacterial infections and some of their most severe consequences, including sepsis. According to the END ...

Feeling anxious about health, family or money is normal for most people--especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. But for those with anxiety disorders, these everyday worries tend to heighten even when there is little or no reason to be concerned.

Researchers from Indiana University School of Medicine recently studied the behaviors associated with anxiety--published in Psychopharmacology--examining how biological factors impact anxiety disorders, specifically in females. They found that anxiety in females intensifies when there's a specific, life-relevant condition.

The team, led by Thatiane De Oliveira Sergio, PhD, postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Woody Hopf, PhD, professor of ...

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual Veterans from the Vietnam era report PTSD and poorer mental health more often than their heterosexual counterparts, according to an analysis of data from the Vietnam Era Health Retrospective Observational Study (VE-HEROeS).

A greater burden of potentially traumatic events among LGB Veterans, such as childhood physical abuse, adult physical assault, and sexual assault, was associated with the differences.

"This study is the first to document sexual orientation differences in trauma experiences, probable PTSD, and health-related quality of life in LGB Veterans using a nationally representative sample," said Dr. John Blosnich, ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Placing rodent traps and bait stations based on rat and mouse behavior could protect the food supply more effectively than the current standard of placing them set distances apart, according to new research from Cornell University.

Rodents cause billions of dollars in losses to the food supply each year, and carry pathogens that can sicken and kill humans, including salmonella, E. coli and Leptospira.

In the 1940s and 50s, scientists recommended that farmers, food manufacturers and distributors evenly space rodent traps or bait boxes in their facilities. But in fact, a new study finds placement based on rat and mouse behavior is more effective.

"From there, it just became a mantra without anybody scientifically evaluating it to see whether this ...

The new study, titled "Liposomal Extravasation and Accumulation in Tumors as Studied by Fluorescence Microscopy and Imaging Depend on the Fluorescent Label," was published on July 1, 2021, in the prestigious journal of the American Chemical Society, ACS Nano.

Liposomes, a type of nanoparticle, are tiny, fat-soluble vesicles (small, fluid-filled sacs) made from lipids, or fats. They are mainly used to deliver cancer-fighting drugs to tumors, since liposomes are not water soluble and can protect some drugs against breaking down in the body.

Comparing fluorescent labels on liposomes ...

The recent extreme heat in the Western United States and Canada may seem remarkable now, but events like these are made more likely, and more severe, under climate change. The consequences are likely to be far-reaching, with overwhelmingly negative impacts on land and ocean ecosystems, biodiversity, food production and the built environment.

"The main lever we have to slow global warming is the rate at which CO2 is added to the atmosphere," said Marcus Thomson, a postdoctoral scholar at the National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis at UC Santa Barbara. Thomson is a co-author of a research article just published in Nature ...

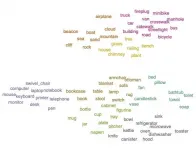

When people see a toothbrush, a car, a tree -- any individual object -- their brain automatically associates it with other things it naturally occurs with, allowing humans to build context for their surroundings and set expectations for the world.

By using machine-learning and brain imaging, researchers measured the extent of the "co-occurrence" phenomenon and identified the brain region involved. The findings appear in Nature Communications.

"When we see a refrigerator, we think we're just looking at a refrigerator, but in our mind, we're also calling up all the other things in a kitchen that we associate with a refrigerator," said corresponding author Mick Bonner, a Johns Hopkins University cognitive scientist. "This is the first time anyone has quantified this and identified ...

A team of the University of Barcelona has analysed for the first time what the dry and hot periods could be like in the area of the Pyrenees depending on different greenhouse emission scenarios. The results, published in the journal Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, show that under an intermediate scenario, where these emissions that accelerate the climate change could be limited, there would not be a rise in long-lasting dry episodes, but temperatures would rise during these periods. On the other hand, if those emissions were not reduced during the 21st century, the summer no-rain periods would last an average ...