(Press-News.org) A new USC study of a common, yet poorly understood type of white blood cell reveals the immune cell's response to pathogens differs greatly by sex and by age.

In this mouse study, males proved much more susceptible to a condition called sepsis than females. However, the scientists also found that the female disease-defense system is hardly perfect; their system changes with age to become nearly as harmful as the males'.

Those are the key findings in a study that appears today in Nature Aging.

The study has important implications for studying disease and cures, especially for sepsis, a condition in which the body's defense system turns harmful to itself. It also suggests that the quest for precision medicine may be overlooking more obvious disease determinants: age and sex.

"A big take-home message is that with the push for personalized medicine, people focus on minute genetic differences, but we find that biological sex - the biggest genetic difference of all - is actually a great predictor for immune response seldom taken into account," said Bérénice Benayoun, assistant professor at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology and principal investigator of the study.

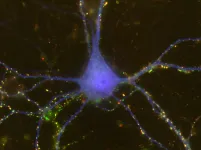

Benayoun and her team focused on cells called "neutrophils," which make up about 50% to 70% of our white blood cells and are critical to fighting off infections. Understanding sex- and age-based differences in how neutrophils function could help us understand similar disparities in human illnesses, such as why older people -- and men in particular-- are more likely to get severe symptoms with COVID-19 or why women are more likely to have autoimmune disorders, she added.

Different defensive tactics

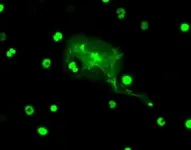

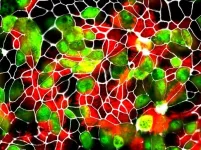

Neutrophils respond to infections in a few different ways, such as by engulfing and digesting an invading pathogen--or by degranulation in which they secrete proteins that destroy the invader.

Another method discovered in 2004 is "NETosis," in which neutrophils expel strands of their own coagulated DNA, called chromatin, which act as a trap outside of the cell. These neutrophil extracellular traps, or so-called "NETs," ensnare and destroy pathogens.

Benayoun and colleagues discovered differences in neutrophil activity between young and old mice, as well as between male and female mice. Males appeared to have more degranulation activity, as evidenced by higher levels of a protein, neutrophil elastase. Meanwhile females exhibited more NETosis on average.

High degranulation activity can cause damage to surrounding tissues, and these findings could illustrate why sepsis affects men more than women, Benayoun said.

"With sepsis, what kills you is not actually the bacteria; it's your response to the bacteria," she noted. "And we know that males in general have much worse odds during sepsis than females, and neutrophil elastase, which is one of the main components of degranulation, is one of the big things that can be produced at very high level during sepsis."

On the other hand, higher NETosis activity could contribute to the body's immune system attacking healthy cells, Benayoun added. Antibodies targeting the body's own DNA have been found in many autoimmune disorders, which could have been developed after neutrophils produced too many NETs. Thus, higher NET activity in females could be related to higher rates of autoimmune disorders in women.

"If you make NETs for no good reason, it can promote autoimmunity," Benayoun said. "It's a known fact that women are more prone to autoimmune disease, like a 9:1 ratio compared to men."

With age, female neutrophils became more reactive, in contrast to male neutrophils. "In general, genetic programs seem to 'age' at a faster rate in male neutrophils," she said. "These findings suggest that sex differences can become amplified with aging, at least for neutrophils."

A new resource for immune system study

Neutrophils have historically been difficult to study because they are so short-lived, lasting less than a day. The cells' short lifespans are spent as the immune system's first responders, working quickly to trap and destroy pathogens at the first sign of an infection and sacrificing themselves in the process.

Applying machine learning techniques to the data, the team has begun to identify genetic pathways involved in the regulation of immune response that could explain why there are such dramatic differences between the sexes, also called sex dimorphism, in immune system activity.

Sex dimorphism in immunity has played out in the current pandemic: Most of the severe COVID-19 cases and deaths were men, Benayoun noted. With other literature indicating a possible role of sex hormones in immunity, studying these interactions could lead scientists to discover new techniques to fight severe illness.

"If these differences are driven by the hormonal effects on immune cells, then in theory, you could try to intervene in early sepsis, maybe with anti-androgens in the short term, to bring down the response," Benayoun mused. "You could tailor medicine just by using the fact that this patient has more androgens or this person has more estrogen."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Benayoun, study co-authors include Ryan J. Lu, Minhoo Kim and Juan Bravo of the USC Leonard Davis School; Shalina Taylor, Kévin Contrepois, and Mathew Ellenberger of Stanford University; and Nirmal K. Sampathkumar of King's College London, U.K.

The work was supported by a Diana Jacobs Kalman/AFAR Scholarships for Research in the Biology of Aging to Lu; GCRLE-2020 post-doctoral fellowship from the Global Consortium for Reproductive Longevity and Equality at the Buck Institute, made possible by the Bia-Echo Foundation, to Kim; NIA T32 AG052374 and NSF graduate research fellowship DGE-1842487 to Bravo; and NIA R00 AG049934, Pew Biomedical Scholar award #00034120, an innovator grant from the Rose Hills Foundation, and the Kathleen Gilmore Biology of Aging research award to Benayoun. This work was also partially supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014089 through the use of shared resources.

WHAT:

A new study published in JAMA Neurology suggests that certain features that appear on CT scans help predict outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury (TBI). Patterns detected on the scans may help guide follow up treatment as well as improve recruitment and research study design for head injury clinical trials.

Researchers led by Geoffrey Manley, M.D., Ph.D., professor of neurological surgery at the University of California San Francisco, conducted CT scans in 1,935 subjects with mild TBI and followed their outcomes up to 12 months after injury.

This research was part of the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) study, a large research effort funded by the National Institutes of ...

Michigan State University ecologists led an international research partnership of professional and volunteer scientists to reveal new insights into what's driving the already-dwindling population of eastern monarch butterflies even lower.

Between 2004 and 2018, changing climate at the monarch's spring and summer breeding grounds has had the most significant impact on this declining population. In fact, the effects of climate change have been nearly seven times more significant than other contributors, such as habitat loss. The team published its report July 19 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

"What we do is develop models to understand why monarchs are declining ...

Determining the major drivers of species diversification and phenotypic innovation across the Tree of Life is one of the grand challeges in evolutionary biology.

Facilitated by the Germplasm Bank of Wild Species of the Kunming Institute of Botany (KIB) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Prof. YI Tingshuang and Prof. LI Dezhu of KIB led a novel study on gymnosperm diversification with a team of international researchers.

This study provides critical insight on the processes underlying diversification and phenotypic evolution in gymnosperms, with important broader implications for the major drivers of both micro- and macroevolution in plants.

The results were published today online in Nature ...

HUNTINGTON, W.Va. - During development, brain cells may find different ways to connect with each other based on sex, according to researchers at the Marshall University Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine.

The study, recently published in eNeuro, an open access journal for the Society of Neuroscience, showed a significantly more robust synaptogenic response in male-derived cells compared to female-derived cells when exposed to factors secreted from astrocytes, which are non-neuronal cells found throughout the central nervous system. This difference was driven largely by how neurons responded to thrombospondin-2 (TSP2), a protein with cell adhesion properties that is normally secreted by astrocytes. ...

Since the beginning of the pandemic, several reports have indicated that SARS-CoV-2 spillover events have occurred from humans to animals, as evidenced by the transmission of the virus between keepers and tigers and lions in the Bronx Zoo in New York. However, to date, the full range of animal species that are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection remains unclear. Typically, such information could be obtained by experimentally infecting a large variety of animal species with SARS-CoV-2 to see if they are susceptible. However, in order to reduce and refine such animal experiments, the researchers at the University of Bern and at the IVI set out to answer this question ...

A new study published in Accident Analysis & Prevention shows how biometric data can be used to find potentially challenging and dangerous areas of urban infrastructure before a crash occurs. Lead author Megan Ryerson led a team of researchers in the Stuart Weitzman School of Design and the School of Engineering and Applied Science in collecting and analyzing eye-tracking data from cyclists navigating Philadelphia's streets. The team found that individual-based metrics can provide a more proactive approach for designing safer roadways for bicyclists and pedestrians.

Current federal rules for installing safe transportation interventions at an unsafe crossing--such as a crosswalk with a traffic signal--require either a minimum of 90-100 pedestrians crossing this location every hour ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Flavor is the name of the game for scientists who want to optimize food for consumption in ways that improve nutrition or combat obesity.

But there is more to flavor than the substances that meet the mouth. Olfaction, our sense of smell, is a major contributor to how we perceive aromas, especially those related to what we eat.

With hopes to capitalize on the smell factor in flavor development, researchers are exploring how the route an aroma takes to get to the olfactory system, through the nose or the back of the throat, influences our response to the scent in question.

In a new study, when participants were asked to match a known scent such as rose with one of four unknown scents, they did best when the aromas were introduced ...

Champaign, IL, July 19, 2021 - For dairy cows, the transition period--the time between a cow giving birth and beginning to produce milk--brings the greatest possibility of health problems. The current widespread belief is that the effects of excess nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) in the bloodstream and the ensuing hyperketonemia during this period, coupled with low levels of available calcium, are largely responsible for disorders such as mastitis, metritis, retained placenta, and poor fertility. Much attention has therefore been devoted to regulating NEFA and calcium levels in transition cows--yet all these efforts have not made the transition period less of a challenge to cows and, hence, to farmers, with approximately ...

The second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine induces a powerful boost to a part of the immune system that provides broad antiviral protection, according to a study led by investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The finding strongly supports the view that the second shot should not be skipped.

"Despite their outstanding efficacy, little is known about how exactly RNA vaccines work," said Bali Pulendran, PhD, professor of pathology and of microbiology and immunology. "So we probed the immune response induced by one of them in exquisite detail."

The study, ...

The MOMAT research group from Universidad Complutense de Madrid has worked with Universidad de Almería, to develop a mathematical model that simulates the impact of SARS-CoV-2 strains and vaccines together, combined with many other biological and social processes in the propagation of COVID-19.

The tool can be downloaded without restriction and free of charge and applied to any territory. It forms part of the family of θ-SIR models, which were initially developed by the MOMAT research group itself before the arrival of new variants and the development of vaccines.

"The model allows us to estimate for the first time ...