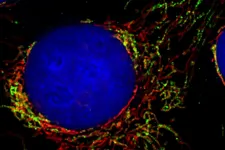

(Press-News.org) Errors in the metabolic processes of mitochondria are responsible for a variety of diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. Scientists needed to find out just how the necessary building blocks are imported into the complex biochemical apparatus of these cell areas. The TOM complex (translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane) is considered the gateway to the mitochondrion, the proverbial powerhouse of the cell. The working group headed by Professor Chris Meisinger at the Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Freiburg has now demonstrated - in human cells - how signaling molecules control this gate. A signaling protein called DYRK1A modifies the molecular machinery of TOM and makes it more permeable for enzymes that are important for the cell metabolism. The group has thus discovered the first signaling protein that directly influences this import process in humans. Their work has been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Developmental disorders in a new light

In neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, microcephaly and Down's syndrome, DYRK1A is defective. "The connection with mitochondria is new. These results allow us to better understand these disorders and develop treatment strategies," says Dr. Adinarayana Marada, a member of Meisinger's team.

"For a long time, researchers thought that the TOM complex was a rigid structure in the mitochondrial membrane whose doors were always open," Meisinger explains. His team recently demonstrated signaling mechanisms in baker's yeast that alter the subunits of the TOM complex depending on the metabolic state of the cell, or in response to sudden stress. In this way, the cell can specifically control the influx of precursor proteins for building elements of the metabolism, and it can adapt the function of the mitochondria to an altered cellular state. Whether such mechanisms also exist in humans was previously unknown.

DYRK1A acts upon the TOM complex

The first authors of the study, Dr. Corvin Walter and Dr. Adinarayana Marada of Meisinger's research group, developed a systematic approach to track down signaling mechanisms such as those triggered by protein kinases, in humans. Over several years, they tested candidates using cell biological and bioinformatic methods and found what they were looking for - DYRK1A, one such protein kinase, acts on the TOM complex. "With this, we actually found the needle in the haystack," says Walter.

INFORMATION:

The work was done in collaboration with Professor Nora Vögtle, Professor Tilman Brummer and Professor Claudine Kraft from the University of Freiburg as well as researchers at the Universities of Göttingen, Dortmund and Fribourg, Switzerland. Meisinger is speaker of the Collaborative Research Center "Dynamic Organization of Cellular Protein Mechanisms" at the University of Freiburg. In addition, he is a member of the Freiburg Cluster of Excellence CIBSS - Centre for Integrative Biological Signalling Studies, the research training group 2202 Transport across and into Membranes, and 2606 ProtPath.

Publication:

Walter, C., Marada, A., Suhm, T., Ernsberger, R., Muders, V., Kücükköse, C., Sánchez-Martín, P., Hu, Z., Aich, A., Loroch, S., Solari, F.A., Poveda-Huertes, D., Schwierzok, A., Pommerening, H., Matic, S., Brix, J., Sickmann, A., Kraft, C., Dengjel, J., Dennerlein, S., Brummer, T., Vögtle, F.N., and Meisinger, C. (2021): Global kinome profiling reveals DYRK1A as critical activator of the human mitochondrial import machinery. In: Nat. Commun. 12:4284. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-24426-9

Three decades ago, child development researchers found that low-income children heard tens of millions fewer words in their homes than their more affluent peers by the time they reached kindergarten. This "word gap" was and continues to be linked to a socioeconomic disparity in academic achievement.

While parenting deficiencies have long been blamed for the word gap, new research from the University of California, Berkeley, implicates the economic context in which parenting takes place -- in other words, the wealth gap.

The findings, published this month in the journal Developmental Science, provide the first evidence that parents may talk less to their kids when experiencing financial scarcity.

"We were interested in what happens when parents think about or experience financial scarcity ...

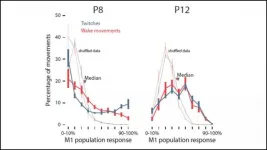

Electrical activity in the motor cortex of rats transforms from redundant to complex over the span of four days shortly after birth. Sleep twitches guide this metamorphosis, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

Despite its name, the motor cortex doesn't control movement right off the bat. Early in development, this part of the brain is solely a sensory structure. Feedback from self-generated movements -- sleep twitches in particular -- may build representations of the body that will later orchestrate movement.

To characterize this transition, Glanz et al. recorded electrical activity from the motor cortex of rat pups eight and 12 days after birth while monitoring their behavior. ...

Politicians may have good reason to turn to angry rhetoric, according to research led by political scientists from Colorado--the strategy seems to work, at least in the short term.

In a new study, Carey Stapleton at the University of Colorado Boulder and Ryan Dawkins at the U.S. Air Force Academy discovered that political furor may spread easily: Ordinary citizens can start to mirror the angry emotions of the politicians they read about in the news. Such "emotional contagion" might even drive some voters who would otherwise tune out of politics to head to the polls.

"Politicians want to get reelected, and anger is a powerful tool that they can use to make that happen," said Stapleton, who recently earned his PhD in political science at ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Did you know multiple sclerosis (MS) means multiple scars? New research shows that the brain and spinal cord scars in people with MS may offer clues to why they developprogressive disability but those with related diseases where the immune system attacks the central nervous system do not.

In a study published in Neurology, Mayo Clinic researchers and colleagues assessed if inflammation leads to permanent scarring in these three diseases:

MS.

Aquaporin-4 antibody positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (AQP4-NMOSD).

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody associated disorder (MOGAD).

They also studied whether scarring may be a reason for ...

For decades, researchers around the world have searched for ways to use solar power to generate the key reaction for producing hydrogen as a clean energy source -- splitting water molecules to form hydrogen and oxygen. However, such efforts have mostly failed because doing it well was too costly, and trying to do it at a low cost led to poor performance.

Now, researchers from The University of Texas at Austin have found a low-cost way to solve one half of the equation, using sunlight to efficiently split off oxygen molecules from water. The finding, published recently in Nature Communications, represents a step forward toward greater adoption ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Plants are DNA hoarders. Adhering to the maxim of never throwing anything out that might be useful later, they often duplicate their entire genome and hang on to the added genetic baggage. All those extra genes are then free to mutate and produce new physical traits, hastening the tempo of evolution.

A new study shows that such duplication events have been vitally important throughout the evolutionary history of gymnosperms, a diverse group of seed plants that includes pines, cypresses, sequoias, ginkgos and cycads. Published today in Nature Plants, the research indicates that ...

FINDINGS

A chemical modification that occurs in some RNA molecules as they carry genetic instructions from DNA to cells' protein-making machinery may offer protection against non-alcoholic fatty liver, a condition that results from a build-up of fat in the liver and can lead to advanced liver disease, according to a new study by UCLA researchers.

The study, conducted in mice, also suggests that this modification -- known as m6A, in which a methyl group attaches to an RNA chain -- may occur at a different rate in females than it does in males, potentially explaining why females tend to have higher fat content in the liver. The researchers found that without the m6A modification, differences in liver fat content between the sexes were reduced dramatically.

In ...

WOODS HOLE, Mass. - What's a hungry marine microbe to do when the pickings are slim? It must capture nutrients - nitrogen, phosphorus, or iron - to survive, yet in vast expanses of the ocean, nutrients are extremely scarce. And the stakes are high: Marine microbial communities drive many of the elemental cycles that sustain all life on Earth.

One ingenious solution to this challenge is reported this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In low-nutrient environments, marine microbes can clump together and hook up with even tinier cells that have vibrating, hairlike appendages (cilia) on their surface. ...

New York, NY--July 19, 2021-- A new robotic neck brace from researchers at Columbia Engineering and their colleagues at Columbia's Department of Otolaryngology may help doctors analyze the impact of cancer treatments on the neck mobility of patients and guide their recovery.

Head and neck cancer was the seventh most common cancer worldwide in 2018, with 890,000 new cases and 450,000 deaths, accounting for 3% of all cancers and more than 1.5% of all cancer deaths in the United States. Such cancer can spread to lymph nodes in the neck, as well as other organs in the body. Surgically removing lymph nodes in the neck can help doctors investigate the risk of spread, but may result in pain and stiffness in the shoulders and neck for years afterward.

Identifying ...

CT scans for patients with concussion provide critical information about their risk for long-term impairment and potential to make a complete recovery - findings that underscore the need for physician follow-up.

In a study led by UC San Francisco, researchers looked at the CT scans of 1,935 patients, ages 17 and over, whose neurological exams met criteria for concussion, or mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), at hospitals throughout the nation. While links between CT imaging features and outcome have already been established in moderate and severe TBI, the researchers believe this is the first time the link has been identified in patients ...