(Press-News.org) Even in their dark isolation from the atmosphere above, caves can hold a rich archive of local climate conditions and how they've shifted over the eons. Formed over tens of thousands of years, speleothems — rock formations unique to caves better known as stalagmites and stalactites — hold secrets to the ancient environments from which they formed.

A newly published study of a stalagmite found in a cave in southern Wisconsin reveals previously undetected history of the local climate going back thousands of years. The new findings provide strong evidence that a series of massive and abrupt warming events that punctuated the most recent ice age likely enveloped vast swaths of the Northern Hemisphere.

The research, conducted by a team of scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, appears March 2 in the journal Nature Geoscience. It's the first study to identify a possible link between ice age warm-ups recorded in the Greenland ice sheet — known as Dansgaard-Oeschger events — and climate records from deep within the interior of central North America.

"This is the only study in this area of the world that is recording these abrupt climate events during the last glacial period," says Cameron Batchelor, who led the analysis while completing her PhD at UW–Madison. Batchelor is now a postdoctoral fellow with the National Science Foundation working at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The study is based on an exceptionally detailed chemical and physical analysis of a stalagmite that formed in the Cave of the Mounds, a tourist attraction and educational destination.

"At Cave of the Mounds our mission is to interpret this geologic wonder for our many annual visitors," says Joe Klimczak, general manager of the cave, which is a designated national natural landmark. "We are thrilled to deepen our understanding of the cave thanks to this world-class research and very exciting results.”

The stalagmite Batchelor and her team analyzed grew extremely slowly — taking roughly 20,000 years to reach the length of a human pinky finger.

The finger-length subterranean rock formed from a complex process that began in the sky. Water that originally fell as precipitation from the atmosphere soaked into the ground and percolated through soil and cracks in bedrock, dissolving tiny bits of limestone along the way. Some of that dissolved limestone was then left behind as countless drips of water fell from the ceiling of Cave of the Mounds, gradually accumulating into thousands of exceedingly thin layers of a mineral called calcite.

"And because those calcite layers are formed from that original precipitation, they're locking in the oxygen in the H2O originating from that precipitation," says Batchelor.

Therein lies the key to reconstructing an ancient climate record from a small, otherwise unremarkable rock. The oxygen trapped in the calcite exists in a couple varieties — known as isotopes — that scientists can use to glean information about the environmental conditions present during the precipitation events that formed it. That includes the temperature and possible sources of rain and snow that fell atop the Cave of the Mounds over thousands of years.

Batchelor's team used a specialized imaging technique that allowed them to identify layers within the stalagmite representing annual growth bands — much like how tree rings record a season’s worth of growth. Using another technique, they identified the isotopes in the tiny layers, revealing that present-day southern Wisconsin experienced a number of very large average temperature swings of up to 10 C (or about 18 F) between 48,000 and 68,000 years ago. Several of the temperature swings occurred over the course of around a decade.

While the dating information is not precise enough to definitively tie the temperature swings to the Dansgaard-Oeschger events recorded in Greenland ice cores, the researchers can say with confidence they occurred within similar timeframes. The team also performed climate simulations that bolstered the hypothesis that warming events occurred tens of thousands of years ago in the region of North America that includes present-day Wisconsin, and that the climate records from Cave of the Mounds and the Greenland ice sheet are indeed linked.

This potential link is exciting for Batchelor because it offers a climate story about central North America that has so far gone untold. Previous research from the mid-continent has not resolved signals of these large temperature swings, also called excursions.

"One theory was that the mid-continent is relatively immune to abrupt climate changes, and that maybe that's because it's surrounded by landmass, and there's some type of buffering happening," says Batchelor. "However, when we went and measured, we saw these really large excursions, and we were like, 'Oh, no, something is definitely happening.'"

That something — a rapidly changing climate — is unfolding yet again today, thanks to humans and our use of fossil fuels. Batchelor says she hopes her work in Wisconsin, and now a cave in the Canadian subarctic that she is studying for her postdoc, helps fill a big data gap about the history and potential future of abrupt climate changes in the mid-continent of North America.

This study was supported by grants from the National Science foundation (P2C2-1805629, EAR-1355590, EAR-1658823). Further resources were provided by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AC05-00OR22725), the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and the Isotope Laboratory at the University of Minnesota. At UW–Madison, Shaun Marcott, Ian Orland and Feng He contributed to this study, as did R. Lawrence Edwards at the University of Minnesota.

END

Wisconsin cave holds tantalizing clues to ancient climate changes, future shifts

2023-03-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Getting drugs across the blood-brain barrier using nanoparticles

2023-03-02

• The blood-brain barrier prevents most drugs from reaching brain tumors.

• A new method using nanoparticles transported drugs across this barrier in mice.

• The nanoparticles target a protein on tumor blood vessel cells called P-selectin.

• The nanoparticles improved the treatment in a model of aggressive pediatric brain cancer

Brain tumors are notoriously hard to treat. One reason is the challenge posed by the blood-brain barrier, a network of blood vessels and tissue with closely spaced cells. The barrier forms a tight seal to protect ...

Insights into the evolution of the sense of fairness

2023-03-02

Göttingen, March 2, 2023. A sense of fairness has long been considered purely human – but animals also react with frustration when they are treated unequally by a person. For instance, a well-known video shows monkeys throwing the offered cucumber at their trainer when a conspecific receives sweet grapes as a reward for the same task. Meanwhile, researchers have observed similarly frustrated reactions to unfair rewards in wolves, rats and crows. However, researchers still debate the reasons for this behavior: Does the frustration really stem from a dislike of unequal treatment, or is there another explanation? In a study with long-tailed ...

Security vulnerabilities detected in drones made by DJI

2023-03-02

Researchers from Bochum and Saarbrücken have detected security vulnerabilities, some of them serious, in several drones made by the manufacturer DJI. These enable users, for example, to change a drone’s serial number or override the mechanisms that allow security authorities to track the drones and their pilots. In special attack scenarios, the drones can even be brought down remotely in flight.

The team headed by Nico Schiller of the Horst Görtz Institute for IT Security at Ruhr University Bochum, ...

Coastal water pollution transfers to the air in sea spray aerosol and reaches people on land

2023-03-02

New research led by Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego has confirmed that coastal water pollution transfers to the atmosphere in sea spray aerosol, which can reach people beyond just beachgoers, surfers, and swimmers.

Rainfall in the US-Mexico border region causes complications for wastewater treatment and results in untreated sewage being diverted into the Tijuana River and flowing into the ocean in south Imperial Beach. This input of contaminated water has caused chronic coastal water pollution in Imperial ...

A bridge between hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity of flax fiber: A breakthrough in the multipurpose oil-water separation field

2023-03-02

The large number of oily wastewater discharges and oil spills are bringing about severe threats to environment and human health. Corresponding to this challenge, a number of functional materials have been developed and applied in oil-water separation as oil barriers or oil sorbents. These materials can be divided into two main categories which are artificial and natural.

Natural materials such as green bio-materials are generally low cost and abundant with biological degradability, which are also regarded as promising alternatives for oil-water separation ...

CityU scholars unify color systems using prime numbers

2023-03-02

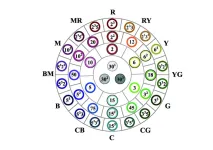

Existing colour systems, such as RGB and CYMK, are all text-based and require a large range of values to represent different colours, making them difficult to compute and time-consuming to convert. Recently, researchers from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) made a breakthrough by inventing an innovative colour system, called “C235”, based on prime numbers, enabling efficient encoding and effective colour compression. It can unify existing colour systems and has the potential to be applied in various applications, like designing an energy-saving LCD system and colourizing DNA codons.

Currently, ...

UCD Archaeologist receives prestigious Dan David Prize for research on the invisible workforce behind ancient forms of art

2023-03-02

The Dan David Prize, the largest history prize in the world, has announced University College Dublin (UCD) Archaeologist, Dr Anita Radini, as one of nine recipients for 2023.

Each of the winners - who work in Kenya, Denmark, Israel, Canada, the US and Ireland - will receive $300,000 (USD) in recognition of their achievements as emerging scholars and to support their future endeavours in the study of the human past. Dr Radini is the first in Ireland to receive this award.

“Our winners represent the next generation of historians,” said Ariel ...

Putting a price tag on the amenity value of private forests

2023-03-02

When it comes to venturing into and enjoying nature, forests are the people’s top choice – at least in Denmark. This is also reflected in the sales prices of properties with private forest. But beyond earnings potential, this first study of its kind, conducted by the University of Copenhagen, puts a price tag on the so-called amenity value of Danish private forests.

Forests have a nearly therapeutic effect on humans. Perhaps that is why eight out of ten of Danes have wandered in the woods over ...

The map to human and animal behavior

2023-03-02

What are humans? What are animals? And what makes humans unique? The comparative psychologist Fumihiro Kano has set himself a life goal to answer those questions. On 28 February 2023 it was announced that the scientist from the Cluster of Excellence “Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behaviour” (CASCB) at the University of Konstanz will receive the Manfred Fuchs Prize from the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities of the State Baden-Württemberg for his interdisciplinary work in animal behaviour research.

Photo gallery for the article: https://www.campus.uni-konstanz.de/en/science/the-map-to-human-behaviour

Fumihiro ...

Resistance training improves sleep quality and reduces inflammation in older people with sarcopenia

2023-03-02

Sarcopenia is the decline of skeletal muscle mass with age, leading to loss of muscle strength (to move objects, shake hands etc.) and performance (walking and making other routine movements effectively). It involves chronic inflammation and is associated with cognitive alterations, heart disease and respiratory disorders. In short, it affects the quality of life, reducing independence and increasing the risk of injury, falls and even death.

Sarcopenia affects 15% of adults over the age of 60 and 46% of those over 80. Sleep disorders are also common in these age groups. The aging ...