(Press-News.org) BOSTON – Mass General researchers have discovered a novel molecular mechanism responsible for the most common forms of acquired hydrocephalus, potentially opening the door to the first-ever nonsurgical treatment for a life-threatening disease that affects about a million Americans. As reported in the journal Cell, the team uncovered in animal models the pathway through which infection or bleeding in the brain triggers a massive neuroinflammatory response that results in increased production of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by tissue known as the choroid plexus, leading to swelling of the brain ventricles.

“Finding a nonsurgical treatment for hydrocephalus, given the fact neurosurgery is fraught with tremendous morbidity and complications, has been the holy grail for our field,” says Kristopher Kahle, MD, PhD, a pediatric neurosurgeon at MGH and senior author of the study. “We’ve identified through a genome-wide analytical approach the mechanism that underlies the swelling of the ventricles which occurs after a brain bleed or brain infection in acquired hydrocephalus. We’re hopeful these findings will pave the way for approval of an anti-inflammatory drug to treat hydrocephalus, which could be a game-changer for populations in the U.S. and around the world that don’t have access to surgery.”

Acquired hydrocephalus occurs in about one of every 500 births globally. It is the most common cause of brain surgery in children, though it can affect people at any age. In underdeveloped parts of the world where bacterial infection is the most prevalent form of the disease, hydrocephalus is often deadly for children due to the lack of surgical intervention. Indeed, the only known treatment for acquired hydrocephalus is brain surgery, which involves implantation of a catheter-like shunt to drain fluid from the brain. But about half of all shunts in pediatric patients fail within two years of placement, according to the Hydrocephalus Association, requiring repeat neurosurgical operations and a lifetime of brain surgeries.

By deciphering the unique cellular and molecular biology that occurs within the brain after infection or severe hemorrhage, the MGH-led research team has taken a major step toward nonsurgical, pharmacologic treatment for humans. Pivotal to the process is the choroid plexus, the brain structure that routinely pumps cerebrospinal fluid into the four ventricles of the brain to keep the organ buoyant and injury-free within the skull. An infection or brain bleed, however, can create a dangerous neuroinflammatory response where the choroid plexus floods the ventricles with cerebral spinal fluid and immune cells from the periphery of the brain – a so-called “cytokine storm,” or immune system overreaction, so often seen in COVID-19 infections--swelling the brain ventricles.

“Scientists in the past thought that entirely different mechanisms were involved in hydrocephalus from infection and from hemorrhage in the brain,” explains co-author Bob Carter, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Neurosurgery at MGH. “Dr. Kahle’s lab found that the same pathway was involved in both types and that it can be targeted with immunomodulators like rapamycin, a drug that’s been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for transplant patients who need to suppress their immune system to prevent organ rejection.”

MGH researchers are continuing to explore how rapamycin and other repurposed drugs which quell the inflammation seen in acquired hydrocephalus could be turned into an effective drug treatment for patients. “What has me most excited is that this noninvasive therapy could provide a way to help young patients who don’t have access to neurosurgeons or shunts,” emphasizes Kahle. “No longer would a diagnosis of hydrocephalus be fatal for these children.”

Kahle is director of Pediatric Neurosurgery at MGH, and director of the Harvard Center for Hydrocephalus and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Carter is chief of Neurosurgery Service at MGH and professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Hydrocephalus Association.

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2021, Mass General was named #5 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America’s Best Hospitals." MGH is a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system.

END

New Insights by Mass General on the molecular mechanism of hydrocephalus could lead to the first-ever non-surgical treatment

A noninvasive way to avoid the repeat failures of shunt placement in patients with hydrocephalus has been the holy grail of scientists in the field

2023-03-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Analyzing child firearm assault injuries by race, ethnicity during pandemic

2023-03-08

About The Study: Child firearm assaults increased substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic in four major U.S. cities, according to the results of this study. Racial and ethnic disparities increased, as Hispanic, Asian, and especially Black children experienced disproportionate shares of the increased violence.

Authors: Jonathan Jay, Dr.P.H., J.D., of the Boston University School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.3125)

Editor’s ...

eDNA holds the key to safeguarding pollinators amid global declines: Study

2023-03-08

Curtin researchers have uncovered new evidence of western pygmy possums interacting with native flowers, providing the first eDNA study to simultaneously detect mammal, insect and bird DNA on flowers.

The new research, published today in Environmental DNA, examined DNA traces left by animal pollinators on native flora and detected both insect and animal pollinators from multiple flowering plant species at once - a game changer in the face of declining animal pollinators globally.

In North America, some pollinator species have fallen by more than 95 per cent while ...

SIAM Conference on Computational Geometric Design (GD23)

2023-03-08

The 2023 SIAM Conference on Computational Geometric Design, organized by the SIAM Activity Group on Geometric Design, is part of the International Geometry Summit bringing together the Symposium on Physical and Solid Modeling 2023, Shape Modeling International 2023, EG Symposium on Geometry Processing 2023, and Geometric Modeling and Processing 2023.

The 2023 SIAM Conference on Computational Geometric Design seeks high quality, original research contributions that strive to advance all aspects ...

Study associates long COVID with physical inactivity

2023-03-08

The link between symptoms of COVID-19 and physical inactivity is increasingly evident. An article recently published in the journal Scientific Reports by researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil describes a study in which COVID-19 survivors with at least one persistent symptom of the disease were 57% more likely to be sedentary, and the presence of five or more post-acute sequelae of infection by SARS-CoV-2 increased the odds of physical inactivity by 138%.

“Although this was a cross-sectional study, the findings underscore the importance of discussing and encouraging physical activity at all times, including during the pandemic,” ...

Scientists uncover the unexpected identity of mezcal worms

2023-03-08

Mezcal is a distilled alcohol made from the boiled and fermented sap of agave plants. Most mezcal beverages — including all brands of tequila — are sold as pure distillates, but a few have an added stowaway bottled inside: worms.

Called gusanos de maguey (Spanish for agave worms), these odd organic chasers aren’t actually worms, but instead a type of insect larva, and their addition to mezcal is a recent one. Mezcal production has a storied history, dating back to the first Spanish inhabitants of Mexico, but larvae were only added to the drink in ...

AERA announces 2023 fellows

2023-03-08

WASHINGTON, March 8, 2023—The American Educational Research Association (AERA) has announced the selection of 24 exemplary scholars as 2023 AERA Fellows. The AERA Fellows Program honors scholars for their exceptional contributions to, and excellence in, education research. Nominated by their peers, the 2023 Fellows were selected by the Fellows Committee and approved by the AERA Council, the association’s elected governing body. They will be inducted during a ceremony at the 2023 Annual Meeting in Chicago on April 14. They join a total of 714 AERA Fellows.

“AERA Fellows demonstrate the highest standards ...

A better way to produce fertilizers

2023-03-08

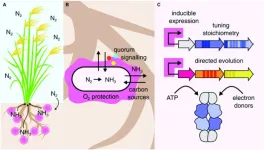

Fertilizers are one of the main reasons that we are able to grow enough crops to feed the almost 8 billion humans living on Earth. Modern agriculture depends largely on nitrogen-based fertilizers, which significantly increase the yield of crops. Unfortunately, a great portion of these fertilizers are produced at an industrial level, consuming fossil fuel energy and causing nitrogen pollution.

One attractive way to minimize our use of industrially produced fertilizers is to harness the power of nitrogenases. ...

University of Cincinnati study finds little federal funding for incarceration-related research

2023-03-08

Research from the University of Cincinnati finds a lack of federal funding for incarceration-related research. The study looked at data from the Department of Justice, National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation, some of which dated back to 1985.

The study was published recently in the journal JAMA Network Open.

“We have very little evidence-based research on how and when to intervene with children and families when someone is removed from the home due to incarceration, especially on how to ...

How nanoplastics can influence metabolism

2023-03-08

PET, the plastic used to make bottles, for example, is ubiquitous in our natural environment. In a joint study, scientists from Leipzig University and the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) investigated the negative effects that tiny plastic PET particles can have on the metabolism and development of an organism. Their findings have now been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The increasing use of plastic is threatening ecosystems around the world. One of the big concerns is the presence of plastics in the form of small particles, also called microplastics and nanoplastics. ...

Virginia Tech researchers study PTSD effects on bystanders

2023-03-08

The traditional line of thought is that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is caused by directly experiencing the traumatic event. However, about 10 percent of diagnosed PTSD occurs when people witness these events versus experiencing it directly themselves.

Little is known about these cases of PTSD, but that’s something that Tim Jarome, an associate professor in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences School of Animal Sciences, is aiming to change with a $430,000 grant from the National Institute ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Breaking the efficiency barrier: Researchers propose multi-stage solar system to harness the full spectrum

A new name, a new beginning: Building a green energy future together

From algorithms to atoms: How artificial intelligence is accelerating the discovery of next-generation energy materials

Loneliness linked to fear of embarrassment: teen research

New MOH–NUS Fellowship launched to strengthen everyday ethics in Singapore’s healthcare sector

Sungkyunkwan University researchers develop next-generation transparent electrode without rare metal indium

What's going on inside quantum computers?: New method simplifies process tomography

This ancient plant-eater had a twisted jaw and sideways-facing teeth

Jackdaw chicks listen to adults to learn about predators

Toxic algal bloom has taken a heavy toll on mental health

Beyond silicon: SKKU team presents Indium Selenide roadmap for ultra-low-power AI and quantum computing

Sugar comforts newborn babies during painful procedures

Pollen exposure linked to poorer exam results taken at the end of secondary school

7 hours 18 mins may be optimal sleep length for avoiding type 2 diabetes precursor

Around 6 deaths a year linked to clubbing in the UK

Children’s development set back years by Covid lockdowns, study reveals

Four decades of data give unique insight into the Sun’s inner life

Urban trees can absorb more CO₂ than cars emit during summer

Fund for Science and Technology awards $15 million to Scripps Oceanography

New NIH grant advances Lupus protein research

New farm-scale biochar system could cut agricultural emissions by 75 percent while removing carbon from the atmosphere

From herbal waste to high performance clean water material: Turning traditional medicine residues into powerful biochar

New sulfur-iron biochar shows powerful ability to lock up arsenic and cadmium in contaminated soils

AI-driven chart review accurately identifies potential rare disease trial participants in new study

Paleontologist Stephen Chester and colleagues reveal new clues about early primate evolution

UF research finds a gentler way to treat aggressive gum disease

Strong alcohol policy could reduce cancer in Canada

Air pollution from wildfires linked to higher rate of stroke

Tiny flows, big insights: microfluidics system boosts super-resolution microscopy

Pennington Biomedical researcher publishes editorial in leading American Heart Association journal

[Press-News.org] New Insights by Mass General on the molecular mechanism of hydrocephalus could lead to the first-ever non-surgical treatmentA noninvasive way to avoid the repeat failures of shunt placement in patients with hydrocephalus has been the holy grail of scientists in the field