In a study published in eLife on March 10, the researchers employed a sophisticated method to break down the proteins that make up P. falciparum into the pieces recognized by our immune system, and then exposed them to blood from 198 Ugandan adults and children. The results showed that antibodies bind to many P. falciparum regions that do not generate a long-lived antibody response, an apparent “diversion tactic” that forces the immune system into generating shorter-lived responses.

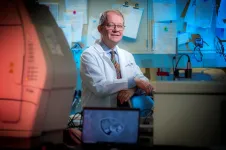

“Malaria is a professional when it comes to immune evasion,” said CZ Biohub SF President Joe DeRisi, co–senior author of the study. “But rather than using stealth, our new findings suggest that the malaria parasite is basically throwing up a fireworks show that distracts the immune system, keeping it chasing targets that ultimately aren’t helpful for developing long-term protection.”

A sophisticated enemy

As for why a durable malaria vaccine has been so hard to come by, experts point to the complexity of the parasite’s life cycle. P. falciparum changes profoundly as it moves through the human body, first gliding through the bloodstream like a single-celled worm and then multiplying in cells of the liver before exploding into the circulatory system to repeatedly devour the contents of red blood cells as fuel to multiply. The parasite is also genetically complex, featuring hundreds of proteins thought to be dedicated to immune evasion. The proteins of the parasite also feature large numbers of simple repeated sequences that have baffled scientists for decades.

In the face of such a sophisticated enemy, it’s perhaps not surprising that both our natural immune responses and efforts to create a vaccine fall short. Only with many repeat exposures across their lifetimes do people in regions of malaria transmission stop becoming sick when infected with the parasite — and sometimes even that’s not enough. The long timeframe to develop immunity leaves children particularly at risk. What’s more, hard-won immunity wanes quickly — people who leave areas of high transmission are likely to lose their protection and get sick again when they return.

These challenges to developing natural immunity have transferred to vaccine efforts. The vaccine known as RTS,S, the first to be approved for malaria, requires a series of four shots and is still only about 30% effective against severe disease, and the protection it confers dwindles after just a few months.

“There’s a lot we just don’t know about how immunity to malaria develops,” said Bryan Greenhouse, a professor of medicine at UCSF and co–senior author of the new paper. “That’s in large part due to a lack of tools to comprehensively characterize the immune system’s response. The new methods we’ve developed here, though, will help close that gap.”

Mapping the immune response

To better understand why it’s so hard to develop malaria immunity, the Biohub SF and UCSF researchers leveraged a powerful technology called PhIP-Seq, which allowed them to analyze in the laboratory how the immune systems of people exposed to P. falciparum have reacted to it. The approach involved taking all of the roughly 5,400 proteins that make up the P. falciparum parasite — the parasite’s “proteome” — and chopping them into hundreds of thousands of chunks, approximating the scale our immune system works on when hunting for pieces of pathogens to target. The researchers then engineered viruses to display each of these tiny chunks — like soldiers waving the flag of an opposing army — and mixed them in laboratory dishes with the blood of study participants.

“What we’ve done is to create a library of all the components of all the proteins malaria could show to our immune system,” said DeRisi, also a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at UCSF. “We can see exactly what our immune system sees and try to figure out how it’s responding.”

Now the researchers could analyze which pieces of the parasite triggered antibodies in human blood to fight off the disease. If the immune system has encountered a chunk before and produced antibodies, then the antibodies should show reactivity to those chunks in the PhIP-seq platform. As expected, samples collected from a control group of U.S. adults, who, for the most part, had probably never been exposed to malaria, showed very little reactivity to protein chunks from the parasite. But when the team looked at blood donated by Ugandans, they observed interesting patterns.

The blood of Ugandans contained antibodies to many components of the malaria parasite but most commonly to protein chunks dubbed “repeat elements.” Repeat elements are areas of a protein where the amino acid sequences that make it up repeat over and over again and are thought to serve little purpose in the protein’s function. Curiously, the response to repeat elements depended heavily on exposure. Ugandan children living with extremely high malaria exposure — an average of 49 times a year through bites from infected mosquitoes — showed about twice as much reactivity to many of these repeat elements than children who lived in areas of moderate exposure — five infected bites per year. But reactivity to some of these repeat elements waned with time more than reactivity to non-repeated regions. The stark difference suggests that while antibodies to these repeat elements dominate the immune response to malaria, this response is fleeting and can disappear more quickly than responses to non-repeated regions.

“Those repeats don’t tend to be very good targets when it comes to creating a long-term defense,” said Madhura Raghavan, a postdoctoral scholar in biochemistry and biophysics at UCSF and lead author of the new study. “Immune resources are limited, and in the case of malaria our bodies seem to be making a major miscalculation in what they’re targeting to create natural immunity.”

DeRisi agreed, adding, “Our immune system jumps into action to deal with these decoys. It’s such a distraction that the body misses the opportunity to develop a defense that would actually be helpful the next time around.”

The findings likely prove an important lesson for vaccine development, which typically relies on mimicking the body’s own immune defense, without necessarily evaluating its effectiveness. Indeed, the RTS,S vaccine uses a P. falciparum repeat element as its target — a possible explanation for its low durability.

Armed with their new library of the P. falciparum proteome, Biohub researchers plan to keep testing immune responses to malaria in Uganda, looking next at how those responses change over time and with different levels of exposure. Additional data, they expect, will eventually guide them to specific components of the parasite proteins that could be key to triggering a more effective immune response via vaccination.

“Unfortunately, malaria is simply a normal part of everyday life for many people and immunity is the only thing keeping them from being continually ill or dying,” Greenhouse said. “It is critical we keep working to understand that immunity better if we want to have a chance at developing an effective, life-saving vaccine."

# # #

The Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Network is a group of nonprofit research institutes that bring together physicians, scientists, and engineers with the goal of pursuing grand scientific challenges on a 10- to 15-year time horizon. These institutes partner with Chan Zuckerberg Science in its goal to understand the mysteries of the cell and how cells interact within systems. This collaboration will bring us closer to our mission to cure, prevent, or manage all disease by the end of the century. To learn more, visit www.czbiohub.org.

END