(Press-News.org) In 2017, a mysterious comet dubbed 'Oumuamua fired the imaginations of scientists and the public alike. It was the first known visitor from outside our solar system, it had no bright coma or dust tail, like most comets, and a peculiar shape — something between a cigar and a pancake — and its small size more befitted an asteroid than a comet.

But the fact that it was accelerating away from the sun in a way that astronomers could not explain perplexed scientists, leading some to suggest that it was an alien spaceship.

Now, a University of California, Berkeley, astrochemist and a Cornell University astronomer argue that the comet's mysterious deviations from a hyperbolic path around the sun can be explained by a simple physical mechanism likely common among many icy comets: outgassing of hydrogen as the comet warmed up in the sunlight.

What made 'Oumuamua different from every other well-studied comet in our solar system was its size: It was so small that its gravitational deflection around the sun was slightly altered by the tiny push created when hydrogen gas spurted out of the ice.

Most comets are essentially dirty snowballs that periodically approach the sun from the outer reaches of our solar system. When warmed by sunlight, a comet ejects water and other molecules, producing a bright halo or coma around it and often tails of gas and dust. The ejected gases act like the thrusters on a spacecraft to give the comet a tiny kick that alters its trajectory slightly from the elliptical orbits typical of other solar system objects, such as asteroids and planets.

When discovered, 'Oumuamua had no coma or tail and was too small and too far from the sun to capture enough energy to eject much water, which led astronomers to speculate wildly about its composition and what was pushing it outward. Was it a hydrogen iceberg outgassing H2? A large, fluffy snowflake pushed by light pressure from the sun? A light sail created by an alien civilization? A spaceship under its own power?

Jennifer Bergner, a UC Berkeley assistant professor of chemistry who studies the chemical reactions that occur on icy rocks in the cold vacuum of space, thought there might be a simpler explanation. She broached the subject with a colleague, Darryl Seligman, now an National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow at Cornell University, and they decided to work together to test it.

"A comet traveling through the interstellar medium basically is getting cooked by cosmic radiation, forming hydrogen as a result. Our thought was: If this was happening, could you actually trap it in the body, so that when it entered the solar system and it was warmed up, it would outgas that hydrogen?" Bergner said. "Could that quantitatively produce the force that you need to explain the non-gravitational acceleration?"

Surprisingly, she found that experimental research published in the 1970s, '80s and '90s demonstrated that when ice is hit by high-energy particles akin to cosmic rays, molecular hydrogen (H2) is abundantly produced and trapped within the ice. In fact, cosmic rays can penetrate tens of meters into ice, converting a quarter or more of the water to hydrogen gas.

"For a comet several kilometers across, the outgassing would be from a really thin shell relative to the bulk of the object, so both compositionally and in terms of any acceleration, you wouldn't necessarily expect that to be a detectable effect," she said. "But because 'Oumuamua was so small, we think that it actually produced sufficient force to power this acceleration."

The comet, which was slightly reddish, is thought to have been roughly 115 by 111 by 19 meters in size. While the relative dimensions were fairly certain, however, astronomers couldn't be sure of the actual size because it was too small and distant for telescopes to resolve. The size had to be estimated from the comet’s brightness and how the brightness changed as the comet tumbled. To date, all the comets observed in our solar system — the short-period comets originating in the Kuiper belt and the long-period comets from the more distant Oort cloud have ranged from around 1 kilometer to hundreds of kilometers across.

"What's beautiful about Jenny's idea is that it's exactly what should happen to interstellar comets," Seligman said. "We had all these stupid ideas, like hydrogen icebergs and other crazy things, and it's just the most generic explanation."

Bergner and Seligman will publish their conclusions this week in the journal Nature. Both were postdoctoral fellows at the University of Chicago when they began collaborating on the paper.

Messenger from afar

Comets are icy rocks left over from the formation of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago, so they can tell astronomers about the conditions that existed when our solar system formed. Interstellar comets can also give hints to the conditions around other stars surrounded by planet-forming disks.

"Comets preserve a snapshot of what the solar system looked like when it was in the stage of evolution that protoplanetary disks are now," Bergner said. "Studying them is a way to look back at what our solar system used to look like in the early formation stage."

Faraway planetary systems also seem to have comets, and many are likely to be ejected because of gravitational interactions with other objects in the system, which astronomers know happened over the history of our solar system. Some of these rogue comets should occasionally enter our solar system, providing an opportunity to learn about planet formation in other systems.

"The comets and asteroids in the solar system have arguably taught us more about planet formation than what we've learned from the actual planets in the solar system," Seligman said. "I think that the interstellar comets could arguably tell us more about extrasolar planets than the extrasolar planets we are trying to get measurements of today."

In the past, astronomers published numerous papers about what we can learn from the failure to observe any interstellar comets in our solar system.

Then, 'Oumuamua came along.

On Oct. 19, 2017, on the island of Maui, astronomers using the Pan-STARRS1 telescope, which is operated by the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii in Manoa, first noticed what they thought was either a comet or an asteroid. Once they realized that its tilted orbit and high speed — 87 kilometers per second — implied that it came from outside our solar system, they gave it the name 1I/‘Oumuamua (oh MOO-uh MOO-uh), which is Hawai'ian for “a messenger from afar arriving first.” It was the first interstellar object aside from dust grains ever seen in our solar system. A second, 2I/Borisov, was discovered in 2019, though it looked and behaved more like a typical comet.

As more and more telescopes focused on 'Oumuamua, the astronomers were able to chart its orbit and determine that it had already looped around the sun and was headed out of the solar system.

Because 'Oumuamua's brightness changed periodically by a factor of 12 and varied asymmetrically, it was assumed to be highly elongated and tumbling end over end. Astronomers also noticed a slight acceleration away from the sun larger than seen for asteroids and more characteristic of comets. When comets approach the sun, the water and gases ejected from the surface create a glowing, gaseous coma and release dust in the process. Typically, dust left in the comet's wake becomes visible as one tail, while vapor and dust pushed by light pressure from solar rays produces a second tail pointing away from the sun, plus a little inertial push outward. Other compounds, such as entrapped organic materials and carbon monoxide, also can be released.

Why was it accelerating?

But astronomers could detect no coma, outgassed molecules or dust around 'Oumuamua. In addition, calculations showed that the solar energy hitting the comet would be insufficient to sublimate water or organic compounds from its surface to give it the observed non-gravitational kick. Only hypervolatile gases such as H2, N2 or carbon monoxide (CO) could provide enough acceleration to match observations, given the incoming solar energy.

"We had never seen a comet in the solar system that didn't have a dust coma. So, the non-gravitational acceleration really was weird," Seligman said.

This led to much speculation about what volatile molecules could be in the comet to cause the acceleration. Seligman himself published a paper arguing that if the comet was composed of solid hydrogen — a hydrogen iceberg — it would outgas enough hydrogen in the heat of the sun to explain the strange acceleration. Under the right conditions, a comet composed of solid nitrogen or solid carbon monoxide would also outgas with enough force to affect the comet's orbit.

But astronomers had to stretch to explain what conditions could lead to the formation of solid bodies of hydrogen or nitrogen, which have never been observed before. And how could a solid H2 body survive for perhaps 100 million years in interstellar space?

Bergner thought that outgassing of hydrogen entrapped in ice might be sufficient to accelerate 'Oumuamua. As both an experimentalist and a theoretician, she studies the interaction of very cold ice — chilled to 5 or 10 degrees Kelvin, the temperature of the interstellar medium (ISM) — with the kinds of energetic particles and radiation found in the ISM.

In searching through past publications, she found many experiments demonstrating that high-energy electrons, protons and heavier atoms could convert water ice into molecular hydrogen, and that the fluffy, snowball structure of a comet could entrap the gas in bubbles within the ice. Experiments showed that when warmed, as by the heat of the sun, the ice anneals — changes from an amorphous to a crystal structure — and forces the bubbles out, releasing the hydrogen gas. Ice at the surface of a comet, Bergner and Seligman calculated, could emit enough gas, either in a collimated beam or fan-shaped spray, to affect the orbit of a small comet like 'Oumuamua.

"The main takeaway is that 'Oumuamua is consistent with being a standard interstellar comet that just experienced heavy processing," Bergner said. "The models we ran are consistent with what we see in the solar system from comets and asteroids. So, you could essentially start with something that looks like a comet and have this scenario work."

The idea also explains the lack of a dust coma.

"Even if there was dust in the ice matrix, you're not sublimating the ice, you're just rearranging the ice and then letting H2 get released. So, the dust isn't even going to come out," Seligman said.

'Dark' comets

Seligman said that their conclusion about the source of 'Oumuamua's acceleration should close the book on the comet. Since 2017, he, Bergner and their colleagues have identified six other small comets with no observable coma, but with small non-gravitational accelerations, suggesting that such "dark" comets are common. While H2 is not likely responsible for the accelerations of dark comets, Bergner noted, together with 'Oumuamua they reveal that there is much to be learned about the nature of small bodies in the solar system.

One of these dark comets, 1998 KY26, is the next target for Japan's Hayabusa2 mission, which recently collected samples from the asteroid Ryugu. The 1998 KY26 was thought to be an asteroid until it was identified as a dark comet in December.

"Jenny's definitely right about the entrapped hydrogen. Nobody had thought of that before," he said. "Between discovering other dark comets in the solar system and Jenny's awesome idea, I think it's got to be correct. Water is the most abundant component of comets in the solar system and likely in extrasolar systems, as well. And if you put a water rich comet in the Oort cloud or eject it into the interstellar medium, you should get amorphous ice with pockets of H2."

Because H2 should form in any ice-rich body exposed to energetic radiation, the researchers suspect that the same mechanism would be at work in sun-approaching comets from the Oort cloud at the outer reaches of the solar system, where comets are irradiated by cosmic rays, much like an interstellar comet would be. Future observations of hydrogen outgassing from long-period comets could be used to test the scenario of H2 formation and entrapment.

Many more interstellar and dark comets should be discovered by the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), allowing astronomers to determine if hydrogen outgassing is common in comets. Seligman has calculated that the survey, which will be conducted at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile and is set to become operational in early 2025, should detect between one and three interstellar comets like 'Oumuamua every year, and likely many more that have a telltale coma, like Borisov.

Bergner was supported by a NASA Hubble Fellowship grant. Seligman was supported by the National Science Foundation (AST-17152) and NASA (80NSSC19K0444, NNX17AL71A).

END

Surprisingly simple explanation for the alien comet 'Oumuamua's weird orbit

2017 comet's unusual acceleration explained by hydrogen outgassing from ice

2023-03-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

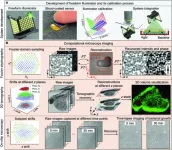

Smaller, denser, better illuminators for computational microscopy

2023-03-22

Seeking to expand the possibilities offered by programmable illumination, a group of researchers at the University of Connecticut developed a strategy for constructing and calibrating freeform illuminators offering greater flexibility for computational microscopy. Their calibration method uses a blood-coated sensor for reconstruction of light source positions. They demonstrated the use of calibrated freeform illuminators for Fourier ptychographic microscopy, 3D tomographic imaging and on-chip microscopy and used a calibrated freeform illuminator in an experiment to track bacterial growth.

The group’s research was published Feb. 20 in Intelligent Computing, a Science ...

Binghamton University reaches highest ever score for LGBTQ+ inclusion

2023-03-22

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- Binghamton University, State University of New York scored a nearly perfect ranking on the latest national Campus Pride Index, which measures a university’s commitment to LGBTQ+ safety and inclusivity on campus. The University received a 4.5 out of 5, an increase from the 3.5 scores received in previous years.

Nicholas Martin, assistant director of the LGBTQ Center at Binghamton University, sees this as a reflection of the organization’s dedication and Binghamton’s real commitment to outreach.

“Our ...

Researchers make biodegradable optical components from crab shells

2023-03-22

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed a process to turn crab shells into a bioplastic that can be used to make optical components known as diffraction gratings. The resulting lightweight, inexpensive gratings are biodegradable and could enable portable spectrometers that are also disposable.

“The Philippines is known for delicious seafood, but this industry is also a source of large amounts of solid waste such as discarded crab shells,” said research team leader Raphael A. Guerrero, from Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. “We wanted to find an alternative use for crab shell ...

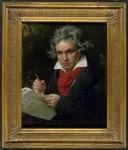

Beethoven’s genome offers clues to composer’s health and family history

2023-03-22

University of Cambridge Media Release

Beethoven’s genome offers clues to composer’s health and family history

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 11:00 US ET / 15:00 UK / 16:00 CET ON WEDNESDAY 22nd MARCH 2023

International team of scientists deciphers renowned composer’s genome from locks of hair.

Study shows Beethoven was predisposed to liver disease, and infected with Hepatitis B, which – combined with his alcohol consumption – may have contributed to his death.

DNA ...

Ludwig von Beethoven’s genome sheds light on chronic health problems and cause of death

2023-03-22

In 1802, Ludwig van Beethoven asked his brothers to request that his doctor, J.A. Schmidt, describe his malady—his progressive hearing loss—to the world upon his death so that "as far as possible at least the world will be reconciled to me after my death." Now, more than two centuries later, a team of researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on March 22 have partially fulfilled his wish by analyzing DNA they lifted and pieced together from locks of his hair.

“Our primary goal was to shed light on Beethoven’s health problems, which famously include progressive hearing loss, beginning in his mid- to late-20s and eventually leading to him ...

Unusual Toxoplasma parasite strain killed sea otters and could threaten other marine life

2023-03-22

Scientists in California are raising the alarm about a newly reported form of toxoplasmosis that kills sea otters and could also infect other animals and people. Although toxoplasmosis is common in sea otters and can sometimes be fatal, this unusual strain appears to be capable of rapidly killing healthy adult otters. This rare strain of Toxoplasma hasn’t been detected on the California coast before, and may be a recent arrival, but scientists are concerned that if it contaminates the marine food chain it could potentially pose a public health risk.

“I have studied Toxoplasma infections in sea otters for 25 years — I have never ...

Sea otters killed by unusual parasite strain

2023-03-22

Four sea otters that stranded in California died from an unusually severe form of toxoplasmosis, according to a study from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the University of California, Davis. The disease is caused by the microscopic parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Scientists warn that this rare strain, never previously reported in aquatic animals, could pose a health threat to other marine wildlife and humans.

The preliminary findings, published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, note that toxoplasmosis is common in sea otters and can be fatal. This unusual strain appears to be especially virulent and capable of rapidly killing healthy adult otters.

The ...

Prevalence of statin use for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by race, ethnicity, 10-year disease risk

2023-03-22

About The Study: Statin use for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was low among all race and ethnicity groups regardless of ASCVD risk, with the lowest use occurring among Black and Hispanic adults in this study of survey data representing 39.4 million adults. Improvements in access to care may promote equitable use of primary prevention statins in Black and Hispanic adults.

Authors: Joshua A. Jacobs, Pharm.D., of the Spencer Fox Eccles University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City, and Ambarish Pandey, M.D., of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, are the corresponding authors.

To ...

Cost-effectiveness of mailed home-based HPV self-sampling kits for cervical cancer screening

2023-03-22

About The Study: In this analysis involving 19,000 female participants, mailing human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling kits to women overdue for cervical cancer screening was cost-effective for increased screening uptake relative to usual care. These results support mailing HPV kits as an efficient outreach strategy for increasing screening rates among eligible women in U.S. health care systems.

Authors: Richard T. Meenan, Ph.D., M.P.H., M.B.A., of Kaiser Permanente Northwest in Portland, Oregon, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link ...

Sweets change our brain

2023-03-22

Chocolate bars, crisps and fries - why can't we just ignore them in the supermarket? Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research in Cologne, in collaboration with Yale University, have now shown that foods with a high fat and sugar content change our brain: If we regularly eat even small amounts of them, the brain learns to consume precisely these foods in the future.

Why do we like unhealthy and fattening foods so much? How does this preference develop in the brain? "Our tendency to eat high-fat and high-sugar foods, the so-called Western diet, could be innate or develop as a result of being overweight. But we think that the brain learns this preference," ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

Scientists develop first-of-its-kind antibody to block Epstein Barr virus

With the right prompts, AI chatbots analyze big data accurately

Leisure-time physical activity and cancer mortality among cancer survivors

Chronic kidney disease severity and risk of cognitive impairment

Research highlights from the first Multidisciplinary Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Symposium

New guidelines from NCCN detail fundamental differences in cancer in children compared to adults

Four NYU faculty win Sloan Foundation research fellowships

Personal perception of body movement changes when using robotic prosthetics

Study shows brain responses to wildlife images can forecast online engagement — and could help conservation messaging

Extreme heat and drought at flowering could put future wheat harvests at risk

Harlequin ichthyosis: a comprehensive review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management

Smithsonian planetary scientists discover recent tectonic activity on the Moon

Government censorship of Chinese chatbots

Incorporating a robotic leg into one’s body image

Brain imaging reveals how wildlife photos open donor wallets

Wiley to expand Advanced Portfolio

Invisible battery parts finally seen with pioneering technique

Tropical forests generate rainfall worth billions, study finds

A yeast enzyme helps human cells overcome mitochondrial defects

Bacteria frozen in ancient underground ice cave found to be resistant against 10 modern antibiotics

Rhododendron-derived drugs now made by bacteria

Admissions for child maltreatment decreased during first phase of COVID-19 pandemic, but ICU admissions increased later

Power in motion: transforming energy harvesting with gyroscopes

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

[Press-News.org] Surprisingly simple explanation for the alien comet 'Oumuamua's weird orbit2017 comet's unusual acceleration explained by hydrogen outgassing from ice