(Press-News.org) UPTON, NY—Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory have produced the first atomic-level structure of an enzyme that selectively cuts carbon-hydrogen bonds—the first and most challenging step in turning simple hydrocarbons into more useful chemicals. As described in a paper just published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, the detailed atomic level “blueprint” suggests ways to engineer the enzyme to produce desired products.

“We want to create a diverse pool of biocatalysts where you can specifically select the desired substrate to produce wanted and unique products from abundant hydrocarbons,” said study co-lead Qun Liu, a Brookhaven Lab structural biologist. “The approach would give us a controllable way to convert cheap and abundant alkanes—simple carbon-hydrogen compounds that make up 20-50 percent of crude oil—into more valuable bioproducts or chemical precursors, including alcohols, aldehydes, carboxylates, and epoxides.”

The idea is particularly attractive because most industrial catalytic processes used for alkane conversions produce unwanted byproducts and heat-trapping carbon dioxide (CO2) gas. They also contain costly materials and require high temperatures and pressure. The biological enzyme, known as AlkB, operates under more ordinary conditions and with very high specificity. It uses inexpensive earth-abundant iron to initiate the chemistry while producing few unwanted byproducts.

“Nature has figured out how to do this kind of chemistry with an inexpensive abundant metal and at ambient temperature and pressures,” said John Shanklin, chair of Brookhaven Lab’s Biology Department and a senior author on the paper. “As a result, there’s been massive interest in this enzyme, but a complete lack of understanding of its architecture and how it works—which is necessary to re-engineer it for new purposes. With this structure, we have now overcome this obstacle.”

From rancid oil to sweet success

AlkB was discovered 50 years ago in a machine shop, where bacteria were digesting cooling oil making it smell rancid. Biochemists discovered the bacterial enzyme AlkB as the factor enabling the microbes’ unusual appetite. Scientists have been interested in harnessing AlkB’s hydrocarbon-chomping ability ever since.

Over the years, studies revealed that the enzyme sits partially embedded in the bacteria’s membranes, and that it operates in conjunction with two other proteins. Shanklin and Liu—and scientists elsewhere—tried solving the enzyme’s structure using x-ray crystallography. That method bounces high-intensity x-rays off a crystallized version of a protein to identify where the atoms are. But membrane proteins like AlkB are notoriously difficult to crystallize—especially when they are part of a multi-protein complex.

“We couldn’t get high enough resolution,” Liu said.

Then in early 2021, Brookhaven opened its new cryo-electron microscope (cryo-EM) facility, the Laboratory for BioMolecular Structure (LBMS). The scientists used a cryo-EM, which does not require a crystallized sample, to take pictures of a few million individual frozen protein molecules from many different angles. Computational tools then sorted through the images, identified and averaged the common features—and ultimately generated a high-resolution, three-dimensional map of the enzyme complex. Using this map, the scientists then pieced together the known atomic-level structures of the individual amino acids that make up the protein complex to fill in the details in three dimensions.

Identifying the right conditions to stabilize the transmembrane region of the enzyme and maintain the structural details was a challenge that required a good deal of trial and error. Shanklin credits Jin Chai, one of the researchers in his lab, “for his commitment and determination to solving this puzzle.”

Structure reveals how enzyme works

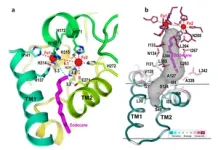

The detailed structure shows exactly how AlkB and one of the two associated proteins (AlkG) work together to cleave carbon-hydrogen bonds. In fact, the solved structure contained an unexpected bonus: a substrate alkane molecule that was trapped in the enzyme’s active site cavity.

“Our structure shows how the amino acids that make up this enzyme form a cavity that orients the hydrocarbon substrate so that just one specific carbon-hydrogen bond can approach the active site,” Liu said. “It also shows how electrons move from the carrier protein (AlkG) to the di-iron center at the enzyme’s active site, allowing it to activate a molecule of oxygen to attack this bond.”

Shanklin suggests thinking of the enzyme as a bond-cutting machine like a circular saw: “How you hold the alkane with respect to the enzyme’s di-iron center determines how the activated oxygen interacts with the hydrocarbon. If you guide the end of the alkane against the activated oxygen, it’s going to initiate some chemistry on that last carbon.

“The engineering we want to do is to change the shape of the active site cavity so we can have the substrate (or a different substrate) approach the activated oxygen at different angles and in different C-H bond locations to perform different reactions.”

In nature, the scientists noted, a third protein not included in this structure (AlkT) provides the electrons to AlkG, the carrier protein. The carrier protein then transports the electrons to the two iron atoms that activate oxygen at AlkB’s active site. Replacing that electron donating protein with an electrode to supply electrons would be simpler and less costly than using the biological electron donor, they suggest.

DOE just funded the team’s proposal to develop such ‘Transformative Biohybrid Diiron Catalysts for C-H Bond Functionalization,’ based in part on this preliminary structural work.

“This structure and our knowledge of how the AlkG/AlkB complex works, puts us in a great position to bioengineer this enzyme to select which carbon-hydrogen bond gets activated in a variety of substrates and to control the electrons and oxygen to re-engineer its selectivity,” Liu said.

This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science (BES) and by Laboratory Directed Research and Development funds at Brookhaven Lab. LBMS is supported by the DOE Office of Science (BER). This research also used resources of Brookhaven Lab’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN), which is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science (BES) User Facility.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

Related Links

Scientific paper: Structural Basis for Enzymatic Terminal C-H Bond Functionalization of Alkanes END

Structure of 'oil-eating' enzyme opens door to bioengineered catalysts

Atomic level details reveal how enzyme selectively breaks hydrocarbon bonds, suggesting bioengineering strategies for making useful chemicals

2023-03-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Allies or enemies of cancer: the dual fate of neutrophils

2023-03-30

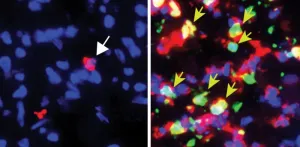

Why do cancer immunotherapies work so extraordinarily well in a minority of patients, but fail in so many others? By analysing the role of neutrophils, immune cells whose presence usually signals treatment failure, scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), from Harvard Medical School, and from Ludwig Cancer Center have discovered that there is not just one type of neutrophils, but several. Depending on certain markers on their surface, these cells can either promote the growth of tumours, or fight them and ensure the success of a treatment. By boosting the appropriate factors, neutrophils could become great agents of anti-tumour ...

Shining light on the mechanics of embryo development

2023-03-30

Summary

Scientists have come up with a new method to study the mechanical properties of developing embryos with unprecedented speed

The new method – line-scanning Brillouin microscopy (LSBM) – relies on a microscopy technique based on Brillouin scattering – a phenomenon where light interacts with naturally occurring thermal vibrations within materials.

The method, which can be used to non-invasively study developing embryos in three dimensions and across time, was selected as one of The Guardian's ...

Buprenorphine initiation in the ER found safe and effective for individuals with opioid use disorder who use fentanyl

2023-03-30

Buprenorphine initiation in the ER found safe and effective for individuals with opioid use disorder who use fentanyl

With historically high overdose death rates in U.S., multi-site NIH study reinforces importance of continued, uninterrupted access to addiction medication

Results from a multi-site clinical trial supported by the National Institutes of Health showed that less than 1% of people with opioid use disorder whose drug use includes fentanyl experienced withdrawal when starting buprenorphine in the ...

Severe hepatitis outbreak linked to common childhood viruses

2023-03-30

A new UC San Francisco-led study brings scientists closer to understanding the causes of a mysterious rash of cases of acute severe hepatitis that began appearing in otherwise healthy children after COVID-19 lockdowns eased in the United States and 34 other countries in the spring of 2022.

Pediatric hepatitis is rare, and doctors were alarmed when they started seeing outbreaks of severe unexplained hepatitis. There have been about 1,000 cases to date; 50 of these children needed liver transplants and at least 22 have died.

In the study, publishing on March 30 in Nature, researchers linked the disease to co-infections from multiple common viruses, in particular a strain of ...

New nanoparticles can perform gene-editing in the lungs

2023-03-30

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Engineers at MIT and the University of Massachusetts Medical School have designed a new type of nanoparticle that can be administered to the lungs, where it can deliver messenger RNA encoding useful proteins.

With further development, these particles could offer an inhalable treatment for cystic fibrosis and other diseases of the lung, the researchers say.

“This is the first demonstration of highly efficient delivery of RNA to the lungs in mice. We are hopeful that it can be used to treat or repair ...

Racial disparities in pathological complete response among patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer

2023-03-30

About The Study: In this study of 690 patients with early-stage breast cancer, racial disparities in response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy were associated with disparities in survival and varied across different breast cancer subtypes. This study highlights the potential benefits of better understanding the biology of primary and residual tumors.

Authors: Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, M.B.B.S., and Dezheng Huo, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Chicago, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.3329)

Editor’s ...

Racial, ethnic, education differences in age of smoking initiation among young adults

2023-03-30

About The Study: Declines in smoking prevalence and increases in the age of smoking initiation occurred more slowly for young adults with less formal education, widening existing education disparities between 2002 and 2019. Black young adults had lower smoking prevalence and older age of smoking initiation than white young adults. However, declines in smoking prevalence and increases in the age of smoking initiation occurred more slowly for this group.

Authors: Alyssa F. Harlow, Ph.D., of the University of Southern California ...

Novel immunotherapy delivery approach safe and beneficial for some melanoma patients with leptomeningeal disease

2023-03-30

HOUSTON ― A novel approach to administer intrathecal (IT) immunotherapy (directly into the spinal fluid) and intravenous (IV) immunotherapy was safe and improved survival in a subset of patients with leptomeningeal disease (LMD) from metastatic melanoma, according to interim analyses of a Phase I/Ib trial led by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The study, published today in Nature Medicine, represents the first-in-human trial of concurrent IT and IV nivolumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma patients ...

Surprise finding shows that neutrophils can be key antitumor weapons

2023-03-30

White blood cells called neutrophils have an unappreciated role in eradicating solid tumors, according to a surprise discovery from a team led by Weill Cornell Medicine scientists.

In the study, published March 30 in Cell, the researchers investigated how a T cell-based immunotherapy was able to destroy melanoma tumors even though many of the tumor cells lacked the markers or “antigens” targeted by the T cells. They found that the T cells, in attacking the tumors, activated a swarm of neutrophils—which in turn killed the tumor cells that the T cells couldn’t ...

Monitoring chronic disease burden: EHRs can help meet a serious public health challenge

2023-03-30

INDIANAPOLIS – The pandemic has highlighted the importance of increasing the flow of information on infectious diseases from electronic health records (EHRs) to public health agencies. Less attention has been paid to the value of EHR data for chronic disease surveillance.

At the HIMSS (Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society) Global Health Conference & Exhibition (HIMSS23), Brian Dixon, PhD, MPA, of Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health and Lorna Thorpe, PhD, MPH, of NYU Grossman School of Medicine, will ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] Structure of 'oil-eating' enzyme opens door to bioengineered catalystsAtomic level details reveal how enzyme selectively breaks hydrocarbon bonds, suggesting bioengineering strategies for making useful chemicals