(Press-News.org) Animals, like humans, appear to be troubled by a Linda problem.

The famous “Linda problem” was designed by psychologists to illustrate how people fall prey to what is known as the conjunction fallacy: the incorrect reasoning that if two events sometimes occur in conjunction, they are more likely to occur together than either event is to occur alone.

Now, for the first time, UCLA psychology researchers have shown that this type of logical error isn’t the sole province of humans — surprisingly, rats seem to make the same mistakes. Their study is published in the journal Psychonomic Bulletin and Review.

“The classical research has all been done with humans, so the usual explanation for the effect attributes it to a departure from rationality distinct to humans,” said Valeria González, a postdoctoral psychology researcher at UCLA and first author of the study. “Our work shows that maybe there is a more general mechanism shared between humans and rats.”

If rats do, as the research findings suggests, succumb to the conjunction fallacy, they could potentially serve as good research models for studying psychopathological conditions characterized by false beliefs or the perception of nonexistent events, like schizophrenia and certain anxiety disorders, the authors said.

But back to Linda. In the 1980s, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tvesrky showed that in a variety of scenarios, humans tend to believe, irrationally, that the intersection of two events is more probable than a single event. They asked participants to answer a question based on the following scenario.

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

Linda is a bank teller.

Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

The great majority of participants chose No. 2, although logically it is less probable than Linda being a bank teller alone. After all, No. 1 would not preclude Linda from also being an active feminist, but given the description of Linda, No. 2 may be easier for respondents to imagine.

The Linda problem and numerous similar studies seem to indicate that humans estimate the likelihood of an event using mental shortcuts, assessing how similar the event is to a model they already have in their minds. The formation of these models, known as representativeness heuristics, relies on a combination of memory, imagination and reasoning universal in humans but thought to be rare or nonexistent in other animals.

Sound, light and the conjunction fallacy in rats

Some have argued that the conjunction fallacy, rather than being a true logical error, may hinge on language, particularly people’s uncertainty about the meaning of words like “likely” and “probability.” Others have pointed out that Linda’s detailed backstory might have biased respondents. But previous research has suggested that humans also are prone to conjunction fallacies when performing physical tasks.

To determine whether the fallacy necessarily involves language and whether it is unique to humans, González engaged rats in a physical, not social, task. With psychology professor Aaron Blaisdell, she designed two experiments that required the rats to judge the likelihood of just a sound being present or both a light and sound being present in order to receive a food reward.

Rats were trained in two scenarios:

Tone + light = reward. In the first, they received sugar pellets if they pressed a lever when a tone played and a steady light was on; they received no food if they pressed they lever when the tone played but the light was off.

Noise alone = reward. In the second scenario, they received pellets if they pressed a lever while a white noise played and a flashing light was off; they received nothing if they pressed the lever when the noise played and the flashing light was on.

The researchers then played the different sounds, a tone or white noise, while the light bulb was unobscured but turned off. The rats reacted accordingly, tending to avoid pressing the lever in response to the tone and pressing it in response to the white noise.

But when researchers obscured the light bulb with a piece of metal and played the sounds, the rats were forced predict whether it was on or off in hopes of receiving the food reward. Interestingly, the rats were much more likely to predict that the obscured light was on. This was true regardless of whether the light had previously signaled the presence or absence of food when accompanying the sound.

The tendency to overestimate the likelihood that both sound and light were present, even if it meant no reward, demonstrates that, like humans, rats can show a conjunction fallacy, the authors said.

“Until now, researchers said this is unique to human cognition only because we haven’t looked for it in animals,” Blaisdell said. “If humans and other animals consider alternative states of the world during ambiguous situations to help decision-making, we might expect systematic biases such as the conjunction fallacy to show a broader distribution in the animal kingdom.”

END

Rats! Rodents seem to make the same logical errors humans do

Both tend to judge the co-occurrence of two events as more probable than one event alone. Could mental shortcuts be to blame?

2023-04-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Impact of cortactin in cancer progression

2023-04-04

“Cortactin (also known as EMS1 or CTTN) is expressed broadly in a variety of cancers [...]”

BUFFALO, NY- April 4, 2023 – A new editorial paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 14 on March 21, 2023, entitled, “Impact of cortactin in cancer progression on Wnt5a/ROR1 signaling pathway.”

In this editorial, researchers Kamrul Hasan and Thomas J. Kipps from the University of California discuss cortactin—an intracellular cytoskeletal protein that can undergo tyrosine phosphorylation upon external stimulation and promote polymerization and the assembly of the actin filament that is required for cell migration. Upon stimulation, cortactin ...

Male beetles neglect their genomes when competing for females

2023-04-04

Male beetles face a trade-off between competing with other males for mating opportunities and repairing damage to their sperm DNA, according to a study publishing April 4th in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Mareike Koppik from Uppsala University, Sweden, and colleagues.

Mutations in sperm and egg DNA can reduce the survival and fitness of offspring, so animals use a variety of repair and maintenance mechanisms in their reproductive cells. However, previous research has shown that sperm DNA has more mutations than egg DNA in a variety of ...

Studies ask: what does “multimorbidity” mean and how much does it cost us?

2023-04-04

The prevalence of multimorbidity, the co-occurrence of two or more chronic conditions, varies depending on exactly how it is defined. And the healthcare costs associated with many disease combinations cost more together than the sum of each individual disease. Those are the conclusions of two new studies, publishing April 4th in the open access journal PLOS Medicine, that broadly analyze the concept and costs of multimorbidity.

Multimorbidity is increasing in prevalence due to improved survival from chronic diseases and population aging, and now poses major challenges to healthcare systems worldwide. ...

SCI Canada Awards event to showcase country’s diverse scientific talent from Nunavut to Ontario

2023-04-04

SCI Canada Awards 2023 dinner, seminar and presentations to take place on 18 April in Toronto

Seminar theme is ‘Unlocking the potential of science talent enabling impact on Canada’s economic growth’

Award winners include the first indigenous community members

Dr Paul Smith, Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, will receive the 2023 Canada Medal

A panel representing the best of Canadian science and industry will discuss its role in boosting economic growth at a special awards event on 18 April in Toronto.

Winners of the 2023 SCI Canada Awards include ...

Scientists use computational modeling to design “ultrastable” materials

2023-04-04

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Materials known as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have a rigid, cage-like structure that lends itself to a variety of applications, from gas storage to drug delivery. By changing the building blocks that go into the materials, or the way they are arranged, researchers can design MOFs suited to different uses.

However, not all possible MOF structures are stable enough to be deployed for applications such as catalyzing reactions or storing gases. To help researchers figure out which MOF structures might work best for a given application, MIT researchers have developed a computational approach that allows ...

Why do females prefer ornate male signals?

2023-04-04

Sexual selection provides an answer to the existence of lavishly ornate signals in animals, but not to the question of why such signals are attractive, why do females prefer the extravagant plumage of peacocks? As part of an international team, researchers at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) have shown that the reason is not the presumed wasteful cost of ornaments, as honest signals need not have to be costly at all as long as cheaters would have to pay to fake them. Researchers have developed a general formula to calculate honest equilibrium in any model, independent of the cost ...

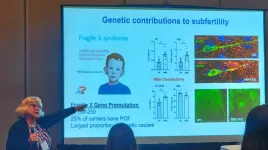

How an autism gene contributes to infertility

2023-04-04

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- A University of California, Riverside, study has identified the biological underpinnings of a reproductive disorder caused by the mutation of a gene. This gene mutation also causes Fragile X Syndrome, a leading genetic cause of intellectual impairment and autism.

The researchers found mutations of the Fragile X messenger ribonucleoprotein 1 gene, or FMR1, contribute to premature ovarian failure, or POF, due to changes in neurons that regulate reproduction in the brain and ovaries. The mutation has been associated with early infertility, due ...

Penn Medicine researchers develop model to predict cardiovascular risk among chronic kidney disease patients

2023-04-04

PHILADELPHIA — Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a strong cardiovascular risk factor and is often accompanied by hypertension and diabetes. Despite the disease’s prevalence—10 percent of individuals across the globe suffer from CKD—there are limited tools for measuring cardiac risk for CKD patients, until now. A new proteomic risk model for cardiovascular disease was found to be more accurate than current methods of measuring cardiac risk, according to a new study led by researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The study published today in the European Heart Journal.

The Penn researchers developed ...

Overwhelmed? Your astrocytes can help with that

2023-04-04

How Little-Known Brain Cells Tamp Down Overexcited Neurons During Acute Stress

A brimming inbox on Monday morning sets your head spinning. You take a moment to breathe and your mind clears enough to survey the emails one by one. This calming effect occurs thanks to a newly discovered brain circuit involving a lesser-known type of brain cell, the astrocyte. According to new research from UC San Francisco, astrocytes tune into and moderate the chatter between overactive neurons.

This new brain circuit, described March 30, 2023 in Nature Neuroscience, plays a role in modulating attention and perception, and may hold a key to treating attention disorders like ...

WPI researcher leads project to determine how stretching and blood flow impact engineered heart valves

2023-04-04

Worcester, Mass. – April 4, 2023 – WPI Researcher Kristen Billiar has been awarded $429,456 from the National Institutes of Health to investigate how stretching and blood flow can inhibit or encourage cardiovascular cells to populate and grow in tissue-engineered heart valves.

The three-year project focuses on experimental valves that are not yet used in humans, and the work will expand understanding about how mechanical forces propel cells in the body.

“Existing heart valves have drawbacks, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Blood test “clocks” predict when Alzheimer’s symptoms will start

Second pregnancy uniquely alters the female brain

Study shows low-field MRI is feasible for breast screening

Nanodevice produces continuous electricity from evaporation

Call me invasive: New evidence confirms the status of the giant Asian mantis in Europe

Scientists discover a key mechanism regulating how oxytocin is released in the mouse brain

Public and patient involvement in research is a balancing act of power

Scientists discover “bacterial constipation,” a new disease caused by gut-drying bacteria

DGIST identifies “magic blueprint” for converting carbon dioxide into resources through atom-level catalyst design

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

[Press-News.org] Rats! Rodents seem to make the same logical errors humans doBoth tend to judge the co-occurrence of two events as more probable than one event alone. Could mental shortcuts be to blame?