(Press-News.org) Many animals have evolved to tolerate extreme environments, including being able to survive crushing pressures of ocean trenches, unforgiving heat of deserts, and limited oxygen high in the mountains. These animals are often highly specialized to live in these specific environments, limiting them from moving to new locations. Yet, there are rare examples of species that once lived in harsh environments but have since colonized more temperate settings. Angel Rivera-Colón, a former graduate student now postdoc in the lab of Julian Catchen (CIS/GNDP), an associate professor in the department of Evolution, Ecology, and Behavior at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, explores the genetic mechanisms underlying this anomaly in Antarctic Notothenioid fish.

Antarctic notothenioids, or cryonotothenioids, have evolved to live in freezing waters around Antarctica, where most fish would otherwise freeze solid if exposed to such cold temperatures. However, cryonotothenioid fish are able to survive in these waters due to antifreeze glycoproteins they produce in their cells. The AGFPs bind to any ice crystals that form, preventing them from growing and the cells from freezing.

Antarctic icefishes, a family within cryonotothenioids, are even more specialized to live in the icy waters. Icefishes also are the only vertebrate that has adapted to live without hemoglobin in their blood cells, causing their cells and tissues to be translucent/white in color. Hemoglobin is a protein in blood cells that helps increase oxygen uptake and results in the red coloration of cells. Normally animals need hemoglobin to get enough oxygen, but in the cold, oxygen-rich waters around Antarctica, icefishes have developed morphological changes, such as bigger hearts for pumping blood, that they no longer need hemoglobin to get enough oxygen.

Despite this extreme specialization, one species of icefish called Champsocephalus esox, or the pike icefish, has escaped Antarctica and now lives in warmer, less oxygenated, South American waters. “The movement of this species to warmer waters posed an interesting evolutionary mystery that I wanted to try to solve,” Rivera-Colón said. “If you’re specialized to only live in very cold environments, how do you survive and adapt to this new warmer environment?”

To understand how the genome of the fish changed as it migrated into warmer waters, Rivera-Colón compared the genetics of the pike icefish to that of an Antarctic species of icefish, C. gunnari. The team took tissue samples collected by collaborators and fishermen from southern Chile, South Georgia, and the Sandwich Islands to sequence the genomes.

“This is the first time we’ve looked at a genome of a notothenioid species that escaped Antarctica into this new temperate environment. A big part of that is because the pike icefish is very rare and elusive, so the help of these fishermen as well as collaborators for gathering samples was indispensable.” Rivera-Colón said. The researchers used continuous long read sequencing to generate a chromosome-level genome for each fish species.

After comparing the genomes, they found that while the genome was highly conserved between the species, there was divergence in areas of the pike icefish genome associated with the physiology that would need to change as the fish moved to warmer waters. Surprisingly, the pike icefish genome still contained multiple copies of the gene that codes for AGFPs, but the genes were full of mutations that may render it non-functional.

“Most of the genes had stop codons inserted in,” Catchen explained. “Assuming everything works as we'd expect, we wouldn't see them transcribed into AGFPs. But the genes are still there and presumably could still active. We’re not sure.” The researchers say that while mutations in this gene in cold water cryonotothenioids could spell death if the gene no longer works, in warmer waters the selection on this gene in pike icefish would’ve loosened, as the fish would no longer need to prevent themselves from freezing.

Researchers also found the pike icefish genome displayed chromosomal inversions — when part of the chromosome becomes flipped in orientation. “We know that inversions and other chromosomal changes can be very important for mediating adaptive processes as well as creating barriers between species,” explained Rivera-Colón. “So finding them here suggests that they could be important for adaptation to the warmer environment in South America.” Rivera-Colón further explained that inversions could make it more difficult for the two species to mix, speeding up speciation between the sister species, despite only splitting less than 2 million years ago.

In addition to evolving to live in warmer waters, the pike icefish would’ve also needed to adapt to a different light environment. The sea around the Antarctic is dark much of the year, and the surface ice blocks much of the light. But in temperate waters, pike icefish experience a more normal day-night cycle. The team is currently examining gene expression in related fish to see how their physiology and circadian rhythms have adapted to these new light cycles.

The researchers also plan to look at the genomes and mitochondria of another pair of related species, Trematomus borchgrevinki and Notothenia angustata. Similar to this study, T. borchgrevinki lives in the cold Antarctic waters, while N. angustata has secondarily transitioned to live in warm waters on the coast of New Zealand. The current study, as well as this planned study on the other species pair, will help researchers better understand how species highly specialized to live in certain environments can escape and adapt to new environments.

“I think one of the really interesting aspects of this study is that it challenges how we tell stories about ‘why evolution acted the way it did’,” Catchen described. “We use the classic story of the icefish to explain loss of hemoglobin due to the cold, oxygenated waters it specializes in, but then you have this species that escaped back to normal temperatures and is managing fine. Selection pushed an organism to the extreme in this direction, and then the environment shifted, and now it's being pushed in a different direction.”

Rivera-Colón added “Our study just goes to show that this specialization for extreme cold is not an evolutionary dead end, and it helps explain how these transitions happen in nature.”

The study, titled “Genomics of secondarily temperate adaptation in the only non-antarctic icefish” was supported by NSF and is published in Molecular Biology & Evolution.

END

A cold-specialized icefish species underwent major genetic changes as it migrated to temperate waters, new study finds

2023-04-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bacterial signaling across biofilm affected by surface structure

2023-04-05

Similar to how cells within human tissues communicate and function together as a whole, bacteria are also able to communicate with each other through chemical signals, a behavior known as quorum signaling (QS). These chemical signals spread through a biofilm that colonies of bacteria form after they reach a certain density, and are used to help the colonies scavenge food, as well as defend against threats, like antibiotics.

“QS helps them to build infrastructure around them, like a city,” ...

Researchers discover new class of ribosomal peptide with hemolytic activity

2023-04-05

Living organisms produce a myriad of natural products which can be used in modern medicine and therapeutics. Bacteria and other microbes have become the main source for natural products, including a growing family called ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides, or RiPPs. The labs of Douglas Mitchell (MMG), John and Margaret Witt Professor of Chemistry, and Huimin Zhao (CABBI/BSD/GSE/MMG), Steven L. Miller Chair of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have been working in tandem to identify and analyze new RiPPs that could be good candidates ...

Nanoparticle with mRNA appears to prevent, treat peanut allergies in mice

2023-04-05

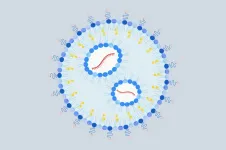

Peanut allergies affect 1 in 50 children, and the most severe cases lead to a potentially deadly immune reaction called anaphylactic shock.

Currently, there is only one approved treatment that reduces the severity of the allergic reaction, and it takes months to kick in. A group of UCLA immunologists is aiming to change that.

Taking inspiration from COVID-19 vaccines as well as their own research on the disease, they created a first-of-its-kind nanoparticle — so small it’s measured in billionths of a meter — that delivers mRNA to specific cells in the liver. Those cells, in turn, teach the body’s natural defenses to tolerate ...

5 Questions with CNSI’s Haley Marks

2023-04-05

Haley Marks is a project scientist for the Advanced Light Microscopy Lab (ALMS) at the CNSI at UCLA. She is a biomedical engineer with a specialty in nano-biosensor research, translational medicine, and optics education.

Since joining CNSI in 2022, Haley has served as a technical expert, providing advanced light microscopy training and services to ALMS users. Here she works on developing and optimizing ALMS’s existing super-resolution and high-speed optical methods, developing strategies and imaging tools for in vivo imaging, and optimizing and disseminating computational imaging techniques.

Haley has a passion for all things photonics, and enjoys 3D printing, materials ...

Young dog owners tend to cope well when their beloved pooch misbehaves, new study reveals

2023-04-05

A new study published in the CABI journal Human-Animal Interactions reveals that young dog owners tend to cope well when their beloved pooch misbehaves.

Past studies suggest that around 90% of dogs display undesired behaviours such as aggression and disobedience, but little is known about the impact of this on young people’s experiences and accompanying emotions.

A team of scientists interviewed young dog owners in Canada, aged 17 to 26 years, to try and determine their experiences with their pets and their coping strategies in response to bad behaviour.

This included barking occasional and persistent barking and, in extreme cases, being aggressive towards other dogs ...

Robots predict human intention for faster builds

2023-04-05

Humans have a way of understandings others’ goals, desires and beliefs, a crucial skill that allows us to anticipate people’s actions. Taking bread out of the toaster? You’ll need a plate. Sweeping up leaves? I’ll grab the green trash can.

This skill, often referred to as “theory of mind,” comes easily to us as humans, but is still challenging for robots. But, if robots are to become truly collaborative helpers in manufacturing and in everyday life, they need to learn the same abilities.

In ...

Hot probe tip contributes to making “transformer” semiconductor particles

2023-04-05

How can we make wearable devices like Spiderman’s suit that are thin and soft yet also feature various electrical and optical functionalities? The answer lies in producing novel materials that go far beyond the performance of existing materials and developing technology that enables the precise control of the physical properties of such materials.

Separating transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) into a single layer just like graphene makes it transform into a thin, two-dimensional (2D) film material that exhibits the characteristics of highly performing semiconductors. By stacking two disparate ...

Series of new studies refute assumptions about link between power and concern about reputation

2023-04-05

Contrary to earlier research findings, people of power - think about politicians, celebrities or bullies in school - turn out to be no less concerned about their reputation, compared to those who have less influence and control within the society.

Previously, it has been assumed that since those who have the upper hand in the society - unlike the ‘powerless’ - are able to get away with commonly unacceptable behaviour (e.g. aggression and exploitation), would care less about any potential damages to their reputation.

However, a recent study by scientists at the University of Kent (United Kingdom) ...

Society matters LIVE: Lab made meat on the menu?

2023-04-04

• Research at Aston University focuses on both creating lab-based meat and its psychological acceptance

• Dr Eirini Theodosiou and Dr Jason Thomas will be speaking at April’s Society matters LIVE event

• Lab made meat on the menu? will take place at Cafe Artum in Hockley Social Club on Thursday 27 April.

Lab made meat will be the topic of the latest Society matters LIVE event from Aston University at Café Artum at Birmingham’s Hockley ...

Students use machine learning in lesson designed to reveal issues, promise of A.I.

2023-04-04

In a new study, North Carolina State University researchers had 28 high school students create their own machine-learning artificial intelligence (AI) models for analyzing data. The goals of the project were to help students explore the challenges, limitations and promise of AI, and to ensure a future workforce is prepared to make use of AI tools.

The study was conducted in conjunction with a high school journalism class in the Northeast. Since then, researchers have expanded the program to high school classrooms in multiple states, including North Carolina. ...