(Press-News.org) At a glance

Dragana Rogulja is using fruit flies and mice to explore tantalizing questions about sleep.

Her research delves into why sleep is necessary for survival, and how the sleeping brain disconnects from the world.

Rogulja’s research has identified a critical connection between the brain and the gut.

If translated into humans, the results of her work could lead to new ways for improving sleep and reducing damage from sleep deprivation.

Sleep is one of the most essential human activities — so essential, in fact, that if we don’t get enough sleep for even one night, we may struggle to think, react, and otherwise make it through the day. Yet, despite its importance for function and survival, scientists still don’t fully understand how sleep works.

Enter Dragana Rogulja, a neurobiologist on a quest to unravel the basic biology of sleep.

As a self-described latecomer to science, Rogulja found herself drawn to questions she considers “broadly interesting and easy to understand on a basic human level.”

One of these questions…What happens when we sleep?

For Rogulja, an associate professor of neurobiology in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, an intriguing aspect of sleep is the loss of consciousness and awareness it brings, as the outside world disappears and the inner world takes over.

In a conversation with Harvard Medicine News, Rogulja delved into the details of her sleep research, which uses fruit flies and mice to explore why we need to sleep and how we disconnect from the world during sleep.

Harvard Medicine News: What are you studying in the context of sleep?

Rogulja: There are two main questions that my lab has been pursuing for the past several years. The first is why sleep is necessary for survival. Why is it that if you don’t sleep, you will literally die after not too long? The other question is how your brain disconnects from the environment when you fall asleep. How are stimuli prevented from reaching your brain during sleep? Elevating the threshold for sensory arousal is essential for sleep, and we want to understand how that barrier is built around the brain. Sleep is one unified state, but it seems to have multiple components that are regulated through separate mechanisms. We want to understand those mechanisms.

HMNews: How has your research changed how you think about sleep?

Rogulja: For a long time, scientists have been guided by the principle that sleep is of the brain, by the brain, and for the brain. As a result, research has largely focused on the brain in terms of looking for reasons why sleep is necessary for survival. However, we are now realizing that while sleep may be for the brain, it’s not just for the brain. Sleep is a super old behavior that we think originated in the earliest animals. These animals had no brain; they only had a very simple nervous system.

Then, as animals became more complex, these brain-related purposes of sleep evolved. However, researchers have looked at the brains of sleep-deprived animals to try to find a reason why they die, and they haven’t found anything. On the other hand, clinical data show that sleep deprivation in humans leads to all kinds of diseases in the body. To us, this really suggested that sleep is about more than just the brain.

Our research tells us that we need to stop thinking about the brain separately from the body when it comes to sleep. I’m still shocked by the degree to which neuroscientists tend to think about the brain as having superiority over the body and being at the top of a hierarchy. To solve the biggest mysteries in neuroscience, we need to take a more integrated approach, which is what my lab is trying to do for sleep. We have found that we really need to think about the whole body to understand sleep. And it makes sense. When you go to sleep, your muscles relax, your circulation changes. Of course, it’s about the whole body.

HMNews: What tools do you use to study sleep?

Rogulja: Historically, a lot of sleep research has been done on humans, but those experiments tend to be limited and descriptive, because you can’t really do experimentation on humans. However, over the last two and a half decades, scientists have come to realize that fruit flies sleep; and more recently, we figured out that the genes that regulate sleep in flies are conserved in mice. When I started my lab, we were only using fruit flies as a model system to study sleep, but we have since been able to establish a mouse model as well. Fruit flies allow us to test a lot of hypotheses quickly and do large, unbiased genetic screens, and then we can test what we find out in flies in mice, which, as mammals, are more similar to humans.

HMNews: In your 2020 Cell paper, you tackled the question of why sleep is necessary for survival. What’s the answer?

We found that fruit flies who slept less had shorter lifespans: We saw a correlation where the more sleep the flies lost, the faster they died. Interestingly, the mode of sleep deprivation did not matter. What mattered was the amount of sleep lost. There seemed to be an inflection point where sleep loss was associated with death, which told us that there might be something specific happening in the body as opposed to general wear and tear.

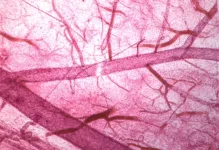

To investigate this further, we stained different organs in sleep-deprived flies with markers of cell damage. We found that in the gut, there was an increase in oxidizing molecules, and the peak of oxidation correlated with the inflection point where the flies started to die. We confirmed this finding in sleep-deprived mice. But when we gave sleep-deprived flies antioxidants or turned on antioxidant-producing genes in the gut, we found the flies could survive on little or no sleep, suggesting that the gut is a really important target of sleep.

HMNews: Are there any possible applications for humans?

Our findings suggest that if we can prevent oxidation in the gut, we might be able to counteract the effect of losing sleep. This is important because a lot of diseases are tied to gut dysfunction, and many diseases that arise when you don’t sleep enough may actually be a consequence of gut damage. We’re now starting to think about how to diagnose gut oxidation due to lack of sleep in humans. We want to design “swallowables” — pills or tablets you could swallow that report the oxidative state of your gut by, for example, changing the color of your feces.

We’re also looking for biomarkers: molecules already circulating in the body that indicate lack of sleep and gut oxidation. I have physicians in my lab who are profiling sleep-deprived mice to look for such biomarkers. We already have some molecules that are promising markers for oxidation and seem to decrease with antioxidant treatments. Eventually, it may be possible to design supplements that could be taken orally to reverse gut oxidation due to lack of sleep.

HMNews: You just published a new paper in Cell that explores how the brain disconnects from the environment during sleep. Tell us more.

Until now, we knew almost nothing about this. It wasn’t clear if there is a single place in the brain where all sensory information is attenuated during sleep, or if there are multiple such places. For example, are touch and temperature processed the same way during sleep? Iris Titos, a postdoctoral researcher in my lab, built a system that can deliver mild, medium, or high levels of vibration to fruit flies. Typically, when you use low-intensity vibrations, very few flies wake up, and when you use high-intensity vibrations, almost all the flies react. Then, we did a large-scale screen to identify genes that control how easily flies wake up — so genes that make flies super easy to wake up, and genes that allow flies to essentially sleep through an earthquake.

HMNews: What did the genetic screen show?

The results of the screen were very interesting. We identified a gene that codes for a molecule called CCHa1. When we depleted CCHa1 in the flies, they woke up very easily — so instead of 20 percent waking up at a particular level of vibration, 90 percent woke up.

However, while CCHa1 is present in both the nervous system and the gut, it was only when we depleted it in the gut that flies were roused more easily. The cells in the gut that produce CCHa1 are called enteroendocrine cells, and they actually share many characteristics with neurons and can even connect and communicate with neurons. These cells face the inside of the gut, and they sort of “taste” the contents of the gut.

We found that the higher concentration of protein in the diet, the more CCHa1 these gut cells produced. This molecule then travels from the gut to the brain, where it signals to a small group of dopaminergic neurons that also receive information about vibrations. These neurons produce dopamine, which usually promotes arousal, but in this case suppresses arousal. Vibrations weaken the activity of the dopaminergic neurons, which causes the flies to wake up more easily. CCHa1 produced by the gut essentially buffers the dopaminergic neurons against vibrations, allowing the flies to ignore the environment to a greater degree and sleep more deeply.

We also found that the CCHa1 pathway, while critical for gating mechanosensory information, has no influence on how easily the flies wake up when exposed to heat, suggesting that different sensory modalities such as vibration and temperature can be gated independently. Finally, we showed that a higher protein diet also improved the quality of sleep in mice, making them more resistant to mechanical disturbances. We are now testing whether a similar signaling pathway is involved in mice.

HMNews: What do these findings tell you?

Well, we know from other research that when animals are starving, they suppress sleep in order to forage. By contrast, when they’re satiated, and especially when they’re satiated with proteins, they tend to sleep more. Now, we’ve shown that when there’s more protein in the diet, animals also sleep more deeply and become less responsive. This suggests that if animals don’t need to look for food, they can disconnect from the environment and hide somewhere to sleep, which might be safer. More broadly, our study implies that dietary choices impact sleep quality. Now we can explore this connection in humans to understand how diet could be manipulated to improve sleep.

HMNews: Is there anything about sleep that you think people often misunderstand?

Rogulja: One thing that I think people should be aware of is that how we feel and what’s going on in our bodies don’t have to be the same. In our research, we found that it’s possible to separate the feeling of sleepiness from the need to sleep — some sleep-deprived animals didn’t necessarily feel sleepy, which we could tell because they didn’t sleep extra to catch up on sleep after the deprivation stopped, but these animals still died from the lack of sleep.

This means that even if we can trick ourselves into not feeling sleepy, the lack of sleep still has negative effects on our bodies — for example, if you take a substance that makes you feel awake, the same amount of oxidation is going to happen in your gut. People may say that they’re OK with only a few hours of sleep a night, but they just mean that they can make it through the day. Their bodies are still going to register the lack of sleep. We really cannot tell what’s happening in our bodies as a result of sleep deprivation, and we probably need more sleep than we think we do.

Authorship, funding, disclosures

Additional authors on the 2023 Cell paper include Alen Juginović, Alexandra Vaccaro, Keishi Nambara, Pavel Gorelik, and Ofer Mazor of HMS.

The research was supported by the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (DP2 OD022385), and the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences.

END

Untangling the mystery of sleep

Recent research on sleep has revealed unexpected connections between the brain and the gut

2023-04-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New nuclear medicine therapy cures human non-hodgkin lymphoma in preclinical model

2023-04-11

Reston, VA—A new nuclear medicine therapy can cure human non-Hodgkin lymphoma in an animal model, according to research published in the April issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. A single dose of the radioimmunotherapy, [177Lu]Lu-ofatumumab, was found to quickly eliminate tumor cells and extend the life of mice injected with cancerous cells for more than 221 days (the trial endpoint), compared to fewer than 60 days for other treatments and just 19 days in untreated control mice.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is a common blood malignancy. The ...

Preprints are the rational choice for satisfying the Nelson Memo requirements

2023-04-11

Preprints allow for free and rapid dissemination of publicly funded research results, and federal agencies should include them in their public access policies as they look to meet the requirements of the US Office of Science and Technology Policy “Nelson Memorandum.” arXiv–the e-print repository for physics, math, computer science and other disciplines–and bioRxiv and medRxiv–preprint servers for biology and the health sciences–address the unique role of preprints and the value they bring as they release their responses to the Nelson Memo.

“US ...

UTA research uses seawater to remove carbon dioxide from atmosphere

2023-04-11

A University of Texas at Arlington researcher is working to create a process that uses seawater to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Erika La Plante, assistant professor in the Materials Science and Engineering Department, received a $125,000 subgrant from the University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) as part of a larger Department of Energy Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy grant for the work.

The UCLA team developed a continuous electrolytic pH pump that uses high-alkalinity seawater with high concentrations of carbon dioxide and cations ...

Daily statin reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV, large NIH study finds

2023-04-11

A National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinical trial was stopped early because a daily statin medication was found to reduce the increased risk of cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV in the first large-scale clinical study to test a primary cardiovascular prevention strategy in this population. A planned interim analysis of data from the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) study found that participants who took pitavastatin calcium, a daily statin, lowered their risk of major adverse cardiovascular ...

Lightning strike creates phosphorus material for the first time on Earth

2023-04-11

TAMPA, Fla. (April 11, 2023) – After lightning struck a tree in a New Port Richey neighborhood, a University of South Florida professor discovered the strike led to the formation of a new phosphorus material. It was found in a rock – the first time in solid form on Earth – and could represent a member of a new mineral group.

“We have never seen this material occur naturally on Earth – minerals similar to it can be found in meteorites and space, but we've never seen this exact material anywhere,” said geoscientist Matthew Pasek.

In a recent study published in Communications Earth & Environment, Pasek examines ...

US natural gas pipelines vulnerable to electric outages

2023-04-11

Natural gas supplies 32% of all primary energy in the United States, its share of electricity generation having nearly doubled from 2008 to 2021. The cross-country natural gas pipeline system used to be powered mainly by natural gas, but recently has switched in places to electric power. The natural gas pipeline system has generally been much more reliable than the electric power system. The new dependence on electricity has created a vulnerability during hurricanes and other events that can take out electric power, since lack of natural gas may in turn cause gas-powered electric ...

How a mutation in the SKD3 enzyme can cause MGCA7 disease

2023-04-11

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and collaborating institutions report in the journal Nature Communications how a mutation in the enzyme SKD3 can cause a form of a genetic disease known as 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (MGCA7). MGCA7 is an inborn error of metabolism associated with variable neurologic deficits and an abnormally low number of immune cells called neutrophils in the blood. The latter condition, known as neutropenia, can lead to increased susceptibility to infection and can also develop into leukemia, as well as early death in infants.

“SKD3 is essential to protein quality control in animal cells. It removes damaged proteins in structures or organelles ...

Study finds only one type of consumer dictates price

2023-04-11

Key Takeaways:

Consumers differ in the way that they shop: some “showroom” by figuring out what they want at one kind of retail outlet and buying elsewhere; others conduct deep research and buy where they first find what they like; and other kinds of consumers are less particular and conduct only fairly limited research.

Consumers who are less choosy may shop at stores that have fewer selections, as long as they can pay a lower price for what they buy. This is the one group of consumers most likely to influence price.

BALTIMORE, MD, April 11, 2023 – It’s ...

Photonic filter separates signals from noise to support future 6G wireless communication

2023-04-11

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed a new chip-sized microwave photonic filter to separate communication signals from noise and suppress unwanted interference across the full radio frequency spectrum. The device is expected to help next-generation wireless communication technologies efficiently convey data in an environment that is becoming crowded with signals from devices such as cell phones, self-driving vehicles, internet-connected appliances and smart city infrastructure.

“This new microwave filter chip has the potential to improve wireless communication, such as 6G, leading to faster internet connections, better overall communication ...

Detecting stress in the office from how people type and click

2023-04-11

In Switzerland, one in three employees suffers from workplace stress. Those affected often don’t realise that their physical and mental resources are dwindling until it’s too late. This makes it all the more important to identify work-related stress as early as possible where it arises: in the workplace.

Researchers at ETH Zurich are now taking a crucial step in this direction. Using new data and machine learning, they have developed a model that can tell how stressed we are just from the way we type and use our mouse.

And there’s more: “How we type on our keyboard and move our mouse seems to be a better predictor of how stressed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New “lock-and-key” chemistry

Benzodiazepine use declines across the U.S., led by reductions in older adults

How recycled sewage could make the moon or Mars suitable for growing crops

Don’t Panic: ‘Humanity’s Last Exam’ has begun

A robust new telecom qubit in silicon

Vertebrate paleontology has a numbers problem. Computer vision can help

Reinforced enzyme expression drives high production of durable lactate-based polyester

In Rett syndrome, leaky brain blood vessels traced to microRNA

Scientists sharpen genetic maps to help pinpoint DNA changes that influence human health traits and disease risk

AI, monkey brains, and the virtue of small thinking

Firearm mortality and equitable access to trauma care in Chicago

Worldwide radiation dose in coronary artery disease diagnostic imaging

Heat and pregnancy

Superagers’ brains have a ‘resilience signature,’ and it’s all about neuron growth

New research sheds light on why eczema so often begins in childhood

Small models, big insights into vision

Finding new ways to kill bacteria

An endangered natural pharmacy hidden in coral reefs

The Frontiers of Knowledge Award goes to Charles Manski for incorporating uncertainty into economic research and its application to public policy analysis

Walter Koroshetz joins Dana Foundation as senior advisor

Next-generation CAR-T designs that could transform cancer treatment

As health care goes digital, patients are being left behind

A clinicopathologic analysis of 740 endometrial polyps: risk of premalignant changes and malignancy

Gibson Oncology, NIH to begin Phase 2 trials of LMP744 for treatment of first-time recurrent glioblastoma

Researchers develop a high-efficiency photocatalyst using iron instead of rare metals

Study finds no evidence of persistent tick-borne infection in people who link chronic illness to ticks

New system tracks blockchain money laundering faster and more accurately

In vitro antibacterial activity of crude extracts from Tithonia diversifolia (asteraceae) and Solanum torvum (solanaceae) against selected shigella species

Qiliang (Andy) Ding, PhD, named recipient of the 2026 ACMG Foundation Rising Scholar Trainee Award

Heat-free gas sensing: LED-driven electronic nose technology enhances multi-gas detection

[Press-News.org] Untangling the mystery of sleepRecent research on sleep has revealed unexpected connections between the brain and the gut