(Press-News.org) JUPITER, Fla. — In a discovery fundamental to the inner workings of cells, scientists have discovered that if oxidative stress damages protein factories called ribosomes, repair crews may move in to help fix the damage so work can quickly resume.

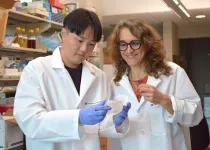

The discovery, reported Friday in the journal Molecular Cell, could have implications for cancer, the aging process, and growth and development, said the study’s lead author, molecular biologist Katrin Karbstein, Ph.D., a professor at The Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology.

“Literally more than half the mass of all cells are ribosomes,” Karbstein said. “If you don’t have enough ribosomes, or they are malfunctioning, proteins aren’t made correctly, and that can lead to all these diseases. We know that defects in the machinery of ribosomes are found in all cancer cells, for example.”

In humans, an individual cell may have 10 million ribosomes whirring away, assembling the proteins spelled out in genes, one amino acid at a time. While many things can damage them — infections, ultraviolet light, radiation or oxidative stress — cells have a remarkable ability to protect themselves. Often, the damaged items are tagged for destruction, cut up and recycled. However, because ribosomes are so important to have in large numbers, destroying every damaged ribosome is problematic.

In their study, Karbstein and colleagues found an alternative way, specific to oxidative stress damage. Oxidative stress occurs in cells when highly reactive oxygen molecules produced by the energy metabolism process must find stable places to land. Often those stable places reside within proteins. The introduction of the excess oxygen can change and damage the receiving molecule. In the case of ribosomes, it can totally stop the work of protein building.

The scientists found that ribosomes fix this undesirable damage with helper molecules, which act like chaperones, escorting the damaged segment away from the cell. The damage is quickly fixed, and the ribosome swings back in action. The cell thus avoids the more intensive process of having to break down and recreate entirely new ribosomes, and risk of having a sudden loss of its ribosome pool.

“Typically when proteins are broken, the cell just degrades them. The ribosome is a very large complex of RNAs and proteins, so maybe if a section gets broken you don’t want to throw out the whole thing,” Karbstein said. “It is like changing a flat tire, rather than buying a new car.”

Biochemistry drives the process. Cysteine amino acid molecules in the ribosome are frequent recipients of these free radical oxygen molecules. Oxidative damage changes them enough that if the chaperone molecules are nearby, they prefer to detach from the ribosome and bind instead to the chaperone. As they exit the ribosome, undamaged amino acids move into their rightful places, fixing the breach and restoring protein production.

The biochemical studies were made possible due to discoveries from the lab of chemist Kate Carroll, Ph.D., also at The Wertheim UF Scripps Institute. Carroll’s lab developed special reagents and processes for monitoring oxidative damage to cystine amino acids.

The first author on the paper was Karbstein lab postdoctoral researcher Yoon-Mo (Jason) Yang, Ph.D. While the discovery was made in yeast, Yang said, this ribosomal repair system appears to be conserved through many species, including humans. Studies of human neurons have suggested a similar phenomenon, for example.

“All living organisms are subjected to oxidative stress, so protein damage happens in all living things,” Yang said. “We suspect that the ribosome repair mechanisms happen in every living thing, including humans.”

Going forward, the scientists have many questions to pursue: They found two chaperones; are there more? Many antibiotics disable ribosomes, so do repair mechanisms in bacteria help them evade antibiotics? Yeast cells lacking the chaperones grow poorly and appear less fit, so could this impact aging, growth and development? These are only a few of the questions the discovery raises, Karbstein said.

“I’m thinking about how we can translate this into the aging paradigm,” Karbstein said. “It’s exactly like filling in a puzzle. You’ve got this piece, then another, and then you say, ‘Oh, that’s how all the pieces come together.’ So, there are many more pieces to be found.”

Other study authors include Youngeun Jung, Ph.D., also of The Wertheim UF Scripps Institute, plus Daniel Abegg, Ph.D., and Alexander Adibekian, Ph.D., now of the University of Chicago.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01GM145886 (AA), F32-GM139302 (YY), R35-GM136323 (KK), R01GM102187 (KSC) and HHMI Faculty Scholar grant 55108536 (KK).

END

Study: Cells send maintenance crews to fix damaged protein factories

2023-04-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New stellar danger to planets identified by NASA'S Chandra program

2023-04-21

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — An exploded star can pose more risks to nearby planets than previously thought, according to a new study from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and other X-ray telescopes. This newly identified threat involves a phase of intense X-rays that can damage the atmospheres of planets up to 160 light-years away.

The results of the study, led by researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Washburn University and the University of Kansas, are published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Earth is not in danger of such a threat today because there are no potential supernova progenitors within this distance, but it may have experienced ...

Why are COVID-19 vaccination rates among children so low? Parents’ worry about long-term risks, responsibility

2023-04-21

Despite efforts by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and pediatric clinicians to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rate among children, many remain unvaccinated due to parental concerns about the vaccine’s long-term effects and anticipated responsibility. Those are findings from a new study published in Pediatricsand conducted by the Center for Economic and Social Research(CESR) at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

The researchers sought to determine the causes of low child vaccination rates. Currently, only 39% of children 5 to 11 and 68% of those 12 to 17 have received ...

Insignum AgTech and Beck’s collaborate to help corn ‘talk’

2023-04-21

ATLANTA, Ind. – Insignum AgTech® and Beck’s have signed an agreement to test Insignum’s innovative corn traits in Beck’s elite varieties. The companies will collaborate to cross the trait into proprietary Beck’s genetics for field-testing in 2023 to evaluate commercial viability of the traits.

Insignum AgTech develops plant genetic traits that enable plants to “talk” and signal to farmers when specific plant stresses begin.

“With this trait, a corn plant generates purple pigment, indicating that a fungal infection has started ...

New study uncovers Colorado’s spicy ancient history of chili peppers

2023-04-21

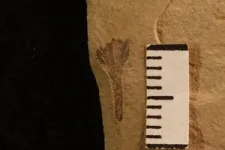

Botanists and paleontologists, led by researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder, have identified a fossil chili pepper that may rewrite the geography and evolutionary timeline of the tomato plant family.

The team’s findings, published last month in the journal New Phytologist, show that the chili pepper tribe (Capsiceae) within the tomato, or nightshade (Solanaceae), family is much older and was much more widespread than previously thought. Scientists previously believed that chili peppers evolved in South America at most ...

360-million-year-old Irish fossil provides oldest evidence of plant self-defense in wood

2023-04-21

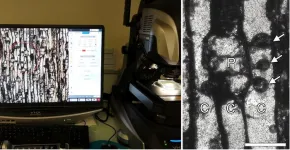

An international team of scientists, co-led by Dr Carla J. Harper, Assistant Professor in Botany in the School of Natural Sciences at Trinity, has discovered the oldest evidence of plant self-defence in wood in a 360-million-year-old fossil from south-eastern Ireland.

Plants can protect their wood from infection and water loss by forming special structures called “tyloses”. These prevent bacterial and fungal pathogens from getting into the heartwood of living trees and damaging it. However, it was not previously known how early in the evolution of plants woody species became capable of forming such defences.

Published ...

New paper advances understanding of geographic health disparities

2023-04-21

By looking at where people were born instead of where they ultimately move to and die, geographic disparities in mortality look different than previously assumed, according to a new study published on April 1, 2023, in the journal Demography.

interstate migration may mitigate regional inequalities in mortality according to “Understanding Geographic Disparities in Mortality,” a paper led by Jason Fletcher, professor in the La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and director of the Center for Demography of Health and Aging with an appointment in Population Health Sciences.

“At a time when nearly ...

Newly funded Morris Animal Foundation study assesses CBD use for postsurgical pain in dogs

2023-04-21

DENVER/April 21, 2023 – A new study is testing whether the addition of CBD can improve pain management in dogs following orthopedic surgery. The study, funded by Morris Animal Foundation, will be conducted by a veterinary research team at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada.

CBD use in pets has gained in popularity in the last decade, but there are few controlled studies closely examining its efficacy as a pain management tool. This study hopes to help partially close this knowledge gap.

The research team, led by Dr. Alan Chicoine, Assistant Professor, Department ...

Endocrine Society endorses bipartisan bill to address insulin affordability

2023-04-21

WASHINGTON—The Endocrine Society today endorsed the Improving Needed Safeguards for Users of Lifesaving Insulin Now (INSULIN) Act of 2023, a bipartisan insulin affordability bill introduced by Sens. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) and Susan Collins (R-ME). This legislation would cap out-of-pocket insulin costs for those with private insurance, ensure patients can share in insulin rebates and discounts, and promote competition in the insulin market.

These measures would protect access to life-saving insulin for more than 7 million people nationwide who rely on the medication to manage their diabetes. According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control ...

Biological age is increased by stress and restored upon recovery

2023-04-21

The biological age of humans and mice undergoes a rapid increase in response to diverse forms of stress, which is reversed following recovery from stress, according to a study publishing on April 21 in the journal Cell Metabolism. These changes occur over relatively short time periods of days or months, according to multiple independent epigenetic aging clocks.

“This finding of fluid, fluctuating, malleable age challenges the longstanding conception of a unidirectional upward trajectory of biological age over the life course,” says co-senior study author James White of Duke University School of Medicine. “Previous reports ...

Most people feel “psychologically close” to climate change

2023-04-21

When spurring action against climate change, NGOs and governmental agencies frequently operate on the assumption that people are unmotivated to act because they view climate change as a problem that affects distant regions far in the future. While this concept, known as psychological distance, seems intuitive, researchers report in the journal One Earth on April 21 that most people see climate change as an important and timely issue even if its impacts are not immediately noticeable.

“There is no consistent evidence ...