(Press-News.org) A major international trial has concluded that, where possible, surgeons should replace the removed section of the skull following surgery to treat a form of brain haemorrhage. This approach will save patients from having to undergo skull reconstruction further down the line.

The RESCUE-ASDH trial, funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), involved 40 centres in 11 countries and involved 450 patients. The results of the trial are published today in the New England Journal of Medicine and are announced at the annual meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

One of the potentially life-threatening results of head injury is a so-called acute subdural haematoma – a bleed that occurs between the brain and skull and can lead to the build-up of pressure. Such haemorrhages require surgery to stem the bleeding, remove the blood clot and relieve the pressure.

At present, there are two approaches to such surgery. One approach is a decompressive craniectomy, which involves leaving a section of the skull out – which can be as large as 13cm in length – in order to protect the patient from brain swelling, often seen with this type of haemorrhage. The missing skull typically will need to be reconstructed and in some treatment centres, the patient’s own bone will be replaced several months after surgery, while at other centres a manufactured plate is used.

The second approach is a craniotomy, in which the skull section is replaced after the haemorrhage has been stemmed and the blood clot removed. This approach will obviate the need for a skull reconstruction further down the line.

To date there has been little conclusive evidence and hence no uniformly accepted criteria for which approach to use. To solve this question, an international team led by researchers at the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust carried out a randomised trial – RESCUE-ASDH – in which patients undergoing surgery for traumatic acute subdural haematoma were randomly assigned to undergo decompressive craniectomy or craniotomy.

A total of 228 patients were assigned to the craniotomy group and 222 to the decompressive craniectomy group. The researchers assessed the outcomes for these patients and their quality of life up to a year after surgery, as measured on clinical evaluation scales.

Patients in both groups had similar disability-related and quality-of-life outcomes at 12 months post-surgery, with a trend – which was not statistically significant – towards better outcomes with craniotomy.

Around one in four patients (25.6%) in the craniotomy group and one in five (19.9%) in the decompressive craniectomy group had a good recovery as measured on the scales.

Around one in three patients in both groups (30.2% of patients in the craniotomy group and 32.2% of those in the decompressive craniectomy group) died within the first 12 months following surgery.

14.6% of the craniotomy group and 6.9% of the decompressive craniectomy group required additional cranial surgery within two weeks after randomisation. However, this was balanced against the fact that fewer people in the craniotomy group experienced wound complications (3.9% against 12.2% of the decompressive craniectomy group).

Professor Peter Hutchinson, Professor of Neurosurgery at Cambridge and the trial's Chief Investigator, said: "The international randomised trial RESCUE-ASDH is the first multicentre study to address a very common clinical question: which technique is optimal for removing an acute subdural haematoma – a craniotomy (putting the bone back) or a decompressive craniectomy (leaving the bone out)?

“This was a large trial and the results convincingly show that there is no statistical difference in the 12 month disability-related and quality of life outcomes between the two techniques.”

Professor Angelos Kolias, Consultant Neurosurgeon at Cambridge and the trial's Co-chief Investigator, said: "Based on the trial findings, we recommend that after removing the blood clot, if the bone flap can be replaced without compression of the brain, surgeons should do so, rather than performing a pre-emptive decompressive craniectomy.

“This approach will save patients from having to undergo a skull reconstruction, which carries the risk of complications and additional healthcare costs, further down the line.”

The researchers point out, however, that the findings may not be relevant for resource-limited or military settings, where pre-emptive decompressive craniectomy is often used owing to the absence of advanced intensive care facilities for post-operative care.

Professor Andrew Farmer, Director of NIHR’s Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme, said: “The findings of this world-leading trial provide important evidence which will improve the way patients with head injuries are treated. High quality, independently funded research like this is vital in providing evidence to improve health and social care practice and treatments. Research is crucial in informing those who plan and provide care.”

The RESCUE-ASDH trial was supported by the NIHR Global Health Research Group on Acquired Brain and Spine Injury, the CENTER-TBI project of the European Brain Injury Consortium, and the Royal College of Surgeons of England Clinical Research Initiative.

Reference

Hutchinson, PJ et al. Decompressive Craniectomy versus Craniotomy for Acute Subdural Hematoma. NEJM; 23 Apr 2023

END

International study recommends replacing skull section after treatment for a brain bleed

2023-04-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Achieving prevention and health, rather than more healthcare

2023-04-23

If more people have access to health insurance, we have to be sure the death rates of those with certain chronic conditions are decreasing.

This is one of the statements Gregory Peck, an acute care surgeon and associate professor at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, will be researching on behalf of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the National Institutes of Health.

Funded by NIH grants totaling more than $1 million through a recent two-year award from the New Jersey Alliance for Clinical and Translational Science (NJ ACTS), a Rutgers hub of the National Center for Advancing ...

Inflammation ‘brake’ gene may help reveal outcomes of kidney disease

2023-04-23

A discovery about gene variants of an inflammation ‘brake’ brings scientists a step closer to personalised treatment for patients at risk of kidney disease and kidney failure.

Researchers at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, University of New South Wales, Sydney and Westmead Hospital, found that common genetic variants of TNFAIP3, which increase inflammation in the body, can paradoxically protect the kidneys from damage in the short term.

“We wanted to investigate whether inherited differences in how people regulate inflammation could lead to better or worse kidney health outcomes,” says Professor Shane ...

Too much insulin can be as dangerous as too little

2023-04-22

Just over a century has passed since the discovery of insulin, a time period during which the therapeutic powers of the hormone have broadened and refined. Insulin is an essential treatment for type 1 diabetes and often for type 2 diabetes, as well. Roughly 8.4 million Americans use insulin, according to the American Diabetes Association.

One hundred years of research have greatly advanced medical and biochemical understanding of how insulin works and what happens when it is lacking, but the reverse, how potentially fatal insulin hyper-responsiveness is prevented, has remained a persistent mystery.

In a new study, published in the April 20, 2023 online edition ...

From sheets to stacks, new nanostructures promise leap for advanced electronics

2023-04-22

Tokyo, Japan – Scientists from Tokyo Metropolitan University have successfully engineered multi-layered nanostructures of transition metal dichalcogenides which meet in-plane to form junctions. They grew out layers of multi-layered structures of molybdenum disulfide from the edge of niobium doped molybdenum disulfide shards, creating a thick, bonded, planar heterostructure. They demonstrated that these may be used to make new tunnel field-effect transistors (TFET), components in integrated circuits with ultra-low power consumption.

Field-effect transistors ...

How alcohol consumption contributes to chronic pain

2023-04-21

LA JOLLA, CA—Chronic alcohol consumption may make people more sensitive to pain through two different molecular mechanisms—one driven by alcohol intake and one by alcohol withdrawal. That is one new conclusion by scientists at Scripps Research on the complex links between alcohol and pain.

The research, published in the British Journal of Pharmacology on April 12, 2023, also suggests potential new drug targets for treating alcohol-associated chronic pain and hypersensitivity.

“There is an urgent need to better ...

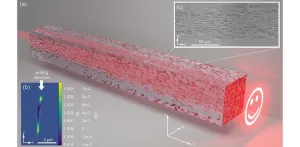

Want to make better materials? Read between the lines. Or the “grain boundaries,” as they’re known in materials science.

2023-04-21

The orientations of these infinitesimally small separations between individual “grains” of a polycrystalline material have big effects. In a material such as aluminum, these collections of grains (called microstructures) determine properties such as hardness.

New research is helping scientists better understand how microstructures change, or undergo “grain growth,” at high temperatures.

A team of materials scientists and applied mathematicians developed a mathematical model that more accurately describes such microstructures by integrating data that can be identified from highly magnified ...

New injectable cell therapy developed by WFIRM scientists could resolve osteoarthritis

2023-04-21

WINSTON-SALEM, NC, April 21, 2023 – Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM) scientists have created a promising injectable cell therapy to treat osteoarthritis that both reduces inflammation and also regenerates articular cartilage.

Recently identified by the Food and Drug Administration as a public health crisis, osteoarthritis affects more than 520 million people worldwide who deal with pain and inflammation. Osteoarthritis is typically induced by mechanical or traumatic stress in the joint, leading to damaged cartilage that cannot be repaired naturally.

“Without better understanding of what drives the initiation and progression of osteoarthritis, effective treatment ...

New approach to developing efficient, high-precision 3D light shapers

2023-04-21

Modern-day technologies like optical computing, integrated photonics, and digital holography require light signals to be manipulated in three dimensions. To achieve this, it is necessary to be able to shape and guide the flow of light according to its desired application. Given that light flow within a medium is governed by the refractive index, specific tailoring of the refractive index is needed to realize control of the light path within the medium.

To this end, scientists have developed what are called “aperiodic photonic ...

New McCombs Award honors Herb Miller

2023-04-21

New McCombs Award Honors Herb Miller

Professional Faculty Impact Award recognizes exceptional contributions of teaching, service, and mentorship.

Associate Professor of Instruction Herb Miller is the namesake and the first recipient of the new McCombs School of Business Marketing Department Herbert A. Miller Jr. Professional Faculty Impact Award.

The award was made possible by William Cunningham, who served as McCombs dean, UT Austin president, and University of Texas System chancellor, as a way to recognize and honor the professional faculty in the department of marketing.

“In ...

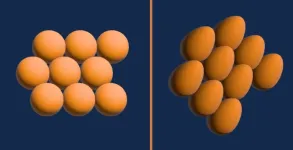

Putting hydrogen on solid ground: Simulations with a machine learning model predict a new phase of solid hydrogen

2023-04-21

Hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, is found everywhere from the dust filling most of outer space to the cores of stars to many substances here on Earth. This would be reason enough to study hydrogen, but its individual atoms are also the simplest of any element with just one proton and one electron. For David Ceperley, a professor of physics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, this makes hydrogen the natural starting point for formulating and testing theories of matter.

Ceperley, also a member of the Illinois Quantum ...