(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. – Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the University of Alaska Anchorage are the first to characterize two different types of surface water in the hyperarid salars—or salt flats—that contain much of the world’s lithium deposits. This new characterization represents a leap forward in understanding how water moves through such basins, and will be key to minimizing the environmental impact on such sensitive, critical habitats.

“You can’t protect the salars if you don’t first understand how they work,” says Sarah McKnight, lead author of the research that appeared recently in Water Resources Research. She completed this work as part of her Ph.D in geosciences at UMass Amherst.

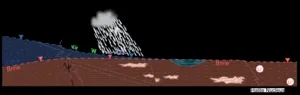

Think of a salar as a giant, shallow depression into which water is constantly flowing, both through surface runoff but also through the much slower flow of subsurface waters. In this depression, there’s no outlet for the water, and because the bowl is in an extremely arid region, the rate of evaporation is such that enormous salt flats have developed over millennia. There are different kinds of water in this depression; generally the nearer the lip of the bowl, the fresher the water. Down near the bottom of the depression, where the salt flats occur, the water is incredibly salty. However, the salt flats are occasionally pocketed with pools of brackish water. Many different kinds of valuable metals can be found in the salt flats—including lithium—while the pools of brackish water are critical habitat for animals like flamingoes and vicuñas.

One of the challenges of studying these systems is that many salars are relatively inaccessible. The one McKnight studies, the Salar de Atacama in Chile, is sandwiched between the Andes and the Atacama Desert. Furthermore, the hydrogeology is incredibly complex: water comes into the system from Andean runoff, as well as via the subsurface aquifer, but the process governing how exactly snow and groundwater eventually turn into salt flat is difficult to pin down.

Add to this the increased mining pressure in the area and the poorly understood effects it may have on water quality, as well as the mega-storms whose intensity and precipitation has increased markedly due to climate change, and you get a system whose workings are difficult to understand.

However, combining observations of surface and groundwater with data from the Sentinel-2 satellite and powerful computer modeling, McKnight and her colleagues were able to see something that has so far remained invisible to other researchers.

It turns out that not all water in the salar is the same. What McKnight and her colleagues call “terminal pools” are brackish ponds of water located in what is called the “transition zone,” or the part of the salar where the water is increasingly briny but has not yet reached full concentration. Then there are the “transitional pools,” which are located right at the boundary between the briny waters and the salt flats. Water comes into each of these pools from different sources—some of them quite far away from the pools they feed—and exits the pools via different pathways.

“It’s important to define these two different types of surface waters,” says McKnight, “because they behave very differently. After a major storm event, the terminal pools flood quickly, and then quickly recede back to their pre-flood levels. But the transitional pools take a very long time—from a few months to almost a year—to recede back to their normal level after a major storm.”

All of this has implications for how these particular ecosystems are managed. “We need to treat terminal and transitional pools differently,” says McKnight, “which means paying more attention to where the water in the pools comes from and how long it takes to get there.”

Parts of this research were funded by the Albemarle Corporation.

Contacts: Sarah McKnight, smcknight@umass.edu

Daegan Miller, drmiller@umass.edu

END

The science behind the life and times of the Earth’s salt flats

New research, led by UMass Amherst, is first to characterize the hydrologic processes of the ecosystems powering the green revolution

2023-05-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

HIV status is not associated with mpox treatment outcomes in persons using tecovirimat

2023-05-02

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 01 May 2023

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

----------------------------

1. ...

Juvenile salmon migration timing responds unpredictably to climate change

2023-05-02

Climate change has led to earlier spring blooms for wildflowers and ocean plankton but the impacts on salmon migration are more complicated, according to new research.

In a new study, published in the journal Nature, Ecology & Evolution, Simon Fraser University (SFU) researcher Sam Wilson led a set of diverse collaborators from across North America to compile the largest dataset in the world on juvenile salmon migration timing. The dataset includes 66 populations from Oregon to B.C. to Alaska. Each dataset was at least 20 years in length with the longest dating back to 1951. Only wild salmon, and not salmon from hatcheries, ...

State study: labor induction doesn’t always reduce caesarean birth risk or improve outcomes for term pregnancies

2023-05-02

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – In recent years, experts have debated whether most birthing individuals would benefit from labor induction once they reach a certain stage of pregnancy.

But a new statewide study in Michigan suggests that inducing labor at the 39th week of pregnancy for people having their first births with a single baby that is in a head down position, or low risk, doesn’t necessarily reduce the risk of caesarian births. In fact, for some birthing individuals, it may even have the opposite effect if hospitals don’t take a thoughtful approach to ...

OSU-Cascades researcher explores AI solution for tracking and reducing household food waste

2023-05-02

BEND, Ore. – A researcher at Oregon State University-Cascades has received funding to develop a smart compost bin that tracks household food waste.

The project led by Patrick Donnelly, assistant professor of computer science in the OSU College of Engineering, seeks to make a dent in a multi-billion-dollar annual problem in the United States: More than one-third of all food produced in the U.S. goes uneaten.

“At every other step of the agricultural supply chain, food waste is tracked, measured and quantified,” Donnelly ...

Survival from cardiac arrest less likely in Asian American Pacific Islander communities

2023-05-02

DALLAS, May 1, 2023 — Science tells us that when a cardiac arrest happens, bystander CPR can double or even triple the chances of survival.[1] Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) adults who experience cardiac arrest outside of a hospital setting have a substantially lower chance of receiving bystander CPR.[2] During Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage month in May, the American Heart Association, a global force for healthier lives for all, is asking people to “Be the Beat” for their family and learn Hands-Only ...

Your health is in your hands during American Stroke Month

2023-05-02

DALLAS, May 1, 2023 — Strokes can happen to anyone, at any age. In fact, globally about one in four adults over the age of 25 will have a stroke in their lifetime.[1] During American Stroke Month, the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association, as part of a nationally supported collaboration with HCA Healthcare and the HCA Healthcare Foundation, will teach people everywhere that stroke is largely preventable, treatable and beatable.

A stroke happens when normal blood flow in the brain is interrupted. When parts of the ...

Blocking a tiny RNA may forestall age-related bone and muscle loss, inflammation

2023-05-02

AUGUSTA, Ga. (May 2, 2023) – Inhibiting a tiny RNA whose levels significantly increase with age, along with problems like weaker bones and sagging muscles, may be a way to keep our bodies more youthful and healthy, scientists say.

MicroRNAs help regulate gene expression and consequently the function of our cells, and several, including one called microRNA-141-3p, have been implicated in the ills of aging, like increasing levels of potentially damaging chronic inflammation and that shrinking muscle mass.

“When we age in all these complications like chronic inflammation, muscle loss, bone loss, this microRNA is elevated,” says Sadanand ...

Fish thought to help reefs have poop that’s deadly to corals

2023-05-02

HOUSTON – (May 2, 2023) – Feces from fish that are typically thought to promote healthy reefs can damage and, in some cases, kill corals, according to a recent study by Rice University marine biologists.

Until recently, fish that consume algae and detritus — grazers — were thought to keep reefs healthy, and fish that eat coral — corallivores — were thought to weaken reef structures. The researchers found high levels of coral pathogens in grazer feces and high levels of beneficial bacteria in corallivore feces, which they say could act like a “coral probiotic.”

“Corallivorous ...

Do people and monkeys see colors the same way?

2023-05-01

New findings in color vision research imply that humans can perceive a greater range of blue tones than monkeys do.

“Distinct connections found in the human retina may indicate recent evolutionary adaptations for sending enhanced color vision signals from the eye to the brain,” researchers report April 25 in the scientific journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Yeon Jin Kim, acting instructor, and Dennis M. Dacey, professor, both in the Department of Biological Structure at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, led the international, collaborative project.

They were joined ...

Organ transplant policies need an overhaul!

2023-05-01

INFORMS Journal Manufacturing & Service Operations Management New Study Key Takeaways:

Matching supply and demand of organs can provide broader sharing in a way that results in greater transplant equity.

By indiscriminately enlarging the pool of supply locations from where patients can receive offers, they tend to become more selective, resulting in more offer rejections and less efficiency.

The model accounts for the variation of “incidence of disease” (i.e., demand) and “availability of deceased-donor organs” ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New study reveals how a key receptor tells apart two nearly identical drug molecules

Parkinson’s disease triggers a hidden shift in how the body produces energy

Eleven genetic variants affect gut microbiome

Study creates most precise map yet of agricultural emissions, charts path to reduce hotspots

When heat flows like water

Study confirms Arctic peatlands are expanding

KRICT develops microfluidic chip for one-step detection of PFAs and other pollutants

How much can an autonomous robotic arm feel like part of the body

Cell and gene therapy across 35 years

Rapid microwave method creates high performance carbon material for carbon dioxide capture

New fluorescent strategy could unlock the hidden life cycle of microplastics inside living organisms

HKUST develops novel calcium-ion battery technology enhancing energy storage efficiency and sustainability

High-risk pregnancy specialists present research on AI models that could predict pregnancy complications

Academic pressure linked to increased risk of depression risk in teens

Beyond the Fitbit: Why your next health tracker might be a button on your shirt

UCSB scientists bottle the sun with liquid battery

Lung cancer drug offers a surprising new treatment against ovarian cancer

When consent meets reality: How young men navigate intimacy

Siemens Healthineers and Mayo Clinic expand strategic collaboration to enhance patient care through advanced technology

Physicists develop new protocol for building photonic graph states

OHSU-led research initiative examines supervised psilocybin

New review identifies pathways for managing PFAS waste in semiconductor manufacturing

New research finds state-level abortion restrictions associated with increased maternal deaths

New study assesses potential dust control options for Great Salt Lake

Science policy education should start on campus

Look again! Those wrinkly rocks may actually be a fossilized microbial community

Exposure to intense wildfire smoke during pregnancy may be linked to increased likelihood of autism

Children with Crohn’s have distinct gut bacteria from kids with other digestive disorders

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

[Press-News.org] The science behind the life and times of the Earth’s salt flatsNew research, led by UMass Amherst, is first to characterize the hydrologic processes of the ecosystems powering the green revolution