(Press-News.org)

New University of Virginia School of Medicine insights into how the brain responds to seizures could facilitate the development of much-needed treatments for the third of patients who don’t respond to existing options.

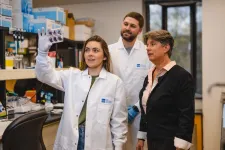

The research, from the labs of UVA’s Ukpong B. Eyo, PhD, and Edward Perez-Reyes, PhD, suggests that immune cells called microglia play important, beneficial roles in controlling various types of seizures. Prior research had left scientists uncertain whether these cells were helpful or harmful during the brain’s seizure response, so UVA’s new discovery offers useful direction for researchers developing new treatments.

“Over the years, there has been debate as to the precise roles of microglia in seizure disorders, and the availability of precise tools to specifically target microglia without affecting other aspects of the brain has been lacking until the approach we have employed in this study,” said Eyo, of UVA’s Department of Neuroscience and Center for Brain Immunology and Glia (BIG Center), as well as the UVA Brain Institute. Our study examined microglial contributions in different models of seizures. [The results] suggest that broadly enhancing microglial activity in patients with different seizure origins could be a promising approach.”

Understanding Seizures

Seizure disorders affect more than 65 million people around the world. In addition to the immediate dangers seizures cause, prolonged seizures called status epilepticus can cause permanent brain damage. Seizures are commonly associated with epilepsy, but they can have a variety of causes, including infections, trauma, and even low blood sugar.

Most existing seizure treatments target nerve cells called neurons, but researchers have increasingly come to appreciate the importance of other cells, such as microglia, in determining how the body responds to seizures. Better understanding the role of microglia could open the door to innovative approaches to preventing and managing seizures.

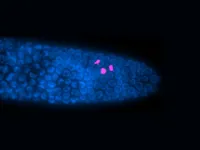

To shed light on the mysterious role of microglia, the UVA researchers eliminated the cells in their lab models of seizures. This allowed them to see what would happen without the microglial response – would lab mice fare better or worse? The results offered clear indications that the microglia were beneficial: Mice lacking the response suffered worse seizures, while mice with normal microglia activity recovered better afterward.

“This study is a great example of UVA’s collaborative culture and the importance of seed funding by the UVA Brain Institute that got the ball rolling” said Perez-Reyes, of UVA’s Department of Pharmacology and the UVA Brain Institute. “We hope to apply this knowledge to develop novel gene therapies for epilepsy and quiet the brain storms that are seizures.”

UVA’s new research has produced several promising leads for scientists to pursue. In particular, Eyo and Perez-Reyes say, additional investigation is needed to determine how exactly the microglia are helping the body control and respond to seizures. This could be by cleaning up excess neurotransmitters, by calming overstimulated neurons or by some other means, they note.

“There is much more work that needs to be done to clarify the precise mechanisms of microglial activity in rodent seizure models and ascertain its translational potential,” Eyo said. “Given our comprehensive research program encompassing both basic science research and clinical research on seizure disorders as well as our strong network of research collaborations, the University of Virginia is a great place to continue to make such advances.”

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the scientific journal Glia. The team consisted of Synphane Gibbs-Shelton, Jordan Benderoth, Ronald P. Gaykema, Justyna Straub, Kenneth A. Okojie, Joseph O. Uweru, Dennis H. Lentferink, Binita Rajbanshi, Maureen N. Cowan, Brij Patel, Anthony Brayan Campos-Salazar, Perez-Reyes and Eyo.

The work was made possible by critical seed funding from the UVA Brain Institute, which builds and supports interdisciplinary neuroscience research teams across UVA to address major societal challenges related to the brain. The seed funding allowed the researchers to lay the groundwork necessary to obtain funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant R01NS122782). Additional support came from The Owens Family Foundation.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

END

Taylor & Francis is delighted to announce the results of Knowledge Unlatched (KU) 2023, with support pledged to convert over 50 book titles to open access (OA). Titles to benefit from this support cover a broad range of humanities and social science disciplines as well as key topic areas, including climate change, global health, and gender studies.

Under the KU crowdfunding model, research libraries around the world unite to support the publication costs of new eBooks and enable access for all to important new research. Since 2016, when Taylor & Francis’ partnership with Knowledge Unlatched began, over 100 books have been published OA at no cost ...

Obesity is a known risk factor for colorectal cancer. Scientists at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) have now shown that this association has probably been significantly underestimated so far. The reason: many people unintentionally lose weight in the years before a colorectal cancer diagnosis. If studies only consider body weight at the time of diagnosis, this obscures the actual relationship between obesity and colorectal cancer risk. In addition, the current study shows that unintentional weight loss may be an early indicator of colorectal ...

Worms might not be depressed, per se. But that doesn’t mean they can’t benefit from antidepressants.

In a new study, Northwestern University researchers exposed roundworms (a well-established model organism in biological research) to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of drugs used for treating depression and anxiety. Surprisingly, this treatment improved the quality of aging females’ egg cells.

Not only did exposure to SSRIs decrease embryonic death by more than twofold, it also decreased chromosomal abnormalities in surviving offspring by more than twofold. Under the microscope, ...

Experts from Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) have published new guidance to help doctors correctly diagnose hoarding disorder.

Hoarding disorder affects around 2% of the population but remains a largely misunderstood mental health condition. It was only added to the International Classification of Diseases in 2019, having previously been classified under Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Published in the British Journal of General Practice, the new guidance was written by Dr Sharon Morein and Dr Sanjiv Ahluwalia of Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) in Cambridge, England, to help health professionals spot the signs of hoarding disorder and intervene.

ARU experts have also organised a free ...

As people get older, they aspire to live healthy lives as free as possible from the natural decline of cognitive abilities that occurs with aging. At Baylor College of Medicine, researchers have been studying the biological underpinnings of age-associated cognitive decline and developing nutritional strategies to promote healthy brain aging.

They report today in the journal Antioxidants that supplementing GlyNAC – a combination of glycine and N-acetylcysteine as precursors of the natural antioxidant glutathione – improved or reversed age-associated cognitive decline in old mice and improved ...

Three New York University faculty have been elected to the National Academy of Sciences: Moses Chao, a professor at NYU Grossman School of Medicine; Glennys Farrar, a professor in NYU’s Department of Physics; and Subhash Khot, a professor in NYU’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. This year’s election of 120 new members and 23 international members were chosen “in recognition of their distinguished and continuing achievements in original research,” the academy announced.

Moses Chau, a professor of cell biology, psychiatry, and neuroscience and physiology and part of ...

(WASHINGTON, May 4, 2023) – Numerous studies have shown that people from racial and ethnic minority groups are underrepresented in clinical trials of new medical treatments for multiple myeloma. A study published today in Blood suggests that, for clinical trials of new treatments for multiple myeloma (a type of blood cancer), one reason for this underrepresentation may be that the parameters set to determine who can – and cannot – enroll in trials disproportionately exclude minority patients.

“Our ...

PHILADELPHIA — (MAY 4, 2023) — The p53 gene is one of the most important in the human genome: the only role of the p53 protein that this gene encodes is to sense when a tumor is forming and to kill it. While the gene was discovered more than four decades ago, researchers have so far been unsuccessful at determining exactly how it works. Now, in a recent study published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, researchers at The Wistar Institute have uncovered a key mechanism ...

A pilot project for energy self-sufficient schools is now starting in the County of Friesland, Northern Germany, in which school buildings will be equipped with vertical-axis wind turbines. This will be facilitated by a research group led by Professor Uygun from Constructor University. This group is studying and developing vertical wind turbines, which will be produced in its own 3D printer on the campus in Bremen and will be tested in practice within this project. This creates a fully functional test field that provides important data and experience for technology transfer.

In the current energy ...

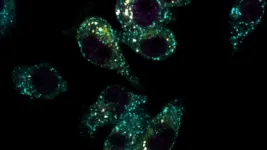

Monash University researchers have discovered a key mechanism in the body’s immune system that helps control the inflammatory response to infection. The discovery could help pave the way for more targeted therapies in a range of inflammatory conditions, such as autoimmunity and neuroinflammatory disease.

The innate immune system is the body’s first line of defence against pathogens. Innate immune proteins detect foreign bodies such as bacteria and viruses and respond by mounting a protective inflammatory ...