(Press-News.org) UPTON, NY—Using some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers, a group of theorists has produced a major advance in the field of nuclear physics—a calculation of the “heavy quark diffusion coefficient.” This number describes how quickly a melted soup of quarks and gluons—the building blocks of protons and neutrons, which are set free in collisions of nuclei at powerful particle colliders—transfers its momentum to heavy quarks.

The answer, it turns out, is very fast. As described in a paper just published in Physical Review Letters, the momentum transfer from the “freed up” quarks and gluons to the heavier quarks occurs at the limit of what quantum mechanics will allow. These quarks and gluons have so many short-range, strong interactions with the heavier quarks that they pull the “boulder”-like particles along with their flow.

The work was led by Peter Petreczky and Swagato Mukherjee of the nuclear theory group at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, and included theorists from the Bielefeld, Regensburg, and Darmstadt Universities in Germany, and the University of Stavanger in Norway.

The calculation will help explain experimental results showing heavy quarks getting caught up in the flow of matter generated in heavy ion collisions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at Europe’s CERN laboratory. The new analysis also adds corroborating evidence that this matter, known as a “quark-gluon plasma” (QGP), is a nearly perfect liquid, with a viscosity so low that it also approaches the quantum limit.

“Initially, seeing heavy quarks flow with the QGP at RHIC and the LHC was very surprising,” Petreczky said. “It would be like seeing a heavy rock get dragged along with the water in a stream. Usually, the water flows but the rock stays.”

The new calculation reveals why that surprising picture makes sense when you think about the extremely low viscosity of the QGP.

Frictionless flow

The low viscosity of matter generated in RHIC’s collisions of gold ions, first reported on in 2005, was a major motivator for the new calculation, Petreczky said. When those collisions melt the boundaries of individual protons and neutrons to set free the inner quarks and gluons, the fact that the resulting QGP flows with virtually no resistance is evidence that there are many strong interactions among the quarks and gluons in the hot quark soup.

“The low viscosity implies that the ‘mean free path’ between the ‘melted’ quarks and gluons in the hot, dense QGP is extremely small,” said Mukherjee, explaining that the mean free path is the distance a particle can travel before interacting with another particle.

“If you think about trying to walk through a crowd, it’s the typical distance you can get before you bump into someone or have to change your course,” he said.

With a short mean free path, the quarks and gluons interact frequently and strongly. The collisions dissipate and distribute the energy of the fast-moving particles and the strongly interacting QGP exhibits collective behavior—including nearly frictionless flow.

“It’s much more difficult to change the momentum of a heavy quark because it’s like a train—hard to stop,” Mukherjee noted. “It would have to undergo many collisions to get dragged along with the plasma.”

But if the QGP is indeed a perfect fluid, the mean free path for the heavy quark interactions should be short enough to make that possible. Calculating the heavy quark diffusion coefficient—which is proportional to how strongly the heavy quarks are interacting with the plasma—was a way to check this understanding.

Crunching the numbers

The calculations needed to solve the equations of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) — the theory that describes quark and gluon interactions — are mathematically complex. Several advances in theory and powerful supercomputers helped to pave the way for the new calculation.

“In 2010/11 we started using a mathematical shortcut, which assumed the plasma consisted only of gluons, no quarks,” said Olaf Kaczmarek of Bielefeld University, who led the German part of this effort. Thinking only of gluons helped the team to work out their method using lattice QCD. In this method, scientists run simulations of particle interactions on a discretized four-dimensional space-time lattice. Essentially, they “place” the particles on discrete positions on an imaginary 3D grid to model their interactions with neighboring particles and see how those interactions change over time (the 4th dimension). They use many different starting arrangements and include varying distances between particles.

After working out the method with only gluons, they figured out how to add in the complexity of the quarks.

The scientists loaded a large number of sample configurations of quarks and gluons onto the 4D lattice and used Monte Carlo methods—repeated random sampling—to try to find the most probable distribution of quarks and gluons within the lattice.

“By averaging over those configurations, you get a correlation function related to the heavy quark diffusion coefficient,” said Luis Altenkort, a University of Bielefeld graduate student who also worked on this research at Brookhaven Lab.

As an analogy, think about estimating the air pressure in a room by sampling the positions and motion of the molecules. “You try to use the most probable distributions of molecules based on another variable, such as temperature, and exclude improbable configurations—such as all the air molecules being clustered in one corner of the room,” Altenkort said.

In the case of the QGP, the scientists were trying to simulate a thermalized system—where even on the tiny-fraction-of-a-second timescale of heavy ion particle collisions, the quarks and gluons come to some equilibrium temperature.

They simulated the QGP at a range of fixed temperatures and calculated the heavy quark diffusion coefficient for each temperature to map out the temperature dependence of the heavy quark interaction strength (and the mean free path of those interactions).

“These demanding calculations were possible only by using some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers,” Kaczmarek said. The computing resources included Perlmutter at the National Energy Research for Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; Juwels Booster at the Juelich Research Center in Germany; Marconi at CINECA in Italy; and dedicated lattice QCD GPU clusters at Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (Jefferson Lab) and at Bielefeld University.

As Mukherjee noted, “These powerful machines don’t just do the job for us while we sit back and relax; it took years of hard work to develop the codes that can squeeze the most efficient performance out of these supercomputers to do our complex calculations.”

The codes were developed as part of a larger collaborative effort known as Fundamental Nuclear Physics at the Exascale and Beyond, which is jointly funded by the DOE Office of Science, Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research and Office of Nuclear Physics through the Scientific Discovery through Advanced Computing (SciDAC) program.

Rapid thermalization, short-range interactions

The calculations show that the heavy quark diffusion coefficient is largest right at the temperature at which the QGP forms, and then decreases with increasing temperatures. This result implies that the QGP comes to an equilibrium extremely rapidly.

“You start with two nuclei, with essentially no temperature, then you collide them and in less than one quadrillionth of a second, you get a thermal system,” Petreczky said. Even the heavy quarks get thermalized.

For that to happen, the heavy quarks have to undergo many scatterings with other particles very quickly — implying that the mean free path of these interactions must be very small. Indeed, the calculations show that, at the transition to QGP, the mean free path of the heavy quark interactions is very close to the shortest distance allowable. That so-called quantum limit is established by the inherent uncertainty of knowing both a particle’s position and momentum simultaneously.

This independent “measure” provides corroborating evidence for the low viscosity of the QGP, substantiating the picture of its perfect fluidity, the scientists say.

“The shorter the mean free path, the lower the viscosity, and the faster the thermalization,” Petreczky said.

Simulating real collisions

Now that scientists know how the heavy quark interactions with the QGP vary with temperature, they can use that information to improve their understanding of how the actual heavy ion collision systems evolve.

“My colleagues are trying to develop more accurate simulations of how the interactions of the QGP affect the motion of heavy quarks,” Petreczky said. “To do that, they need to take into account the dynamical effects of how the QGP expands and cools down — all the complicated stages of the collisions.”

“Now that we know how the heavy quark diffusion coefficient changes with temperature, they can take this parameter and plug it into their simulations of this complicated process and see what else needs to be changed to make those simulations compatible with the experimental data at RHIC and the LHC.”

This effort is the subject of a major collaboration known as the Heavy-Flavor Theory (HEFTY) for QCD Matter Topical Theory Collaboration.

“We’ll be able to better model the motion of heavy quarks in the QGP, and then have a better theory to data comparison,” Petreczky said.

The work was funded by the DOE Office of Science, Office of Nuclear Physics, and by other funders for individual collaborators listed in the scientific paper.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook

Related Links

Scientific paper: "Heavy Quark Diffusion from 2+1 Flavor Lattice QCD"

Heavy Particles Get Caught Up in the Flow END

Calculation shows why heavy quarks get caught up in the flow

New results will help physicists interpret experimental data from particle collisions at RHIC and the LHC and better understand the interactions of quarks and gluons

2023-06-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bilingual, digital health tool helps reduce alcohol use, UC Irvine-led study finds

2023-06-07

Irvine, Calif., June 7, 2023 –– An automated, bilingual, computerized alcohol screening and intervention health tool is effective in reducing alcohol use among Latino emergency department patients in the U.S., according to a study led by the University of California, Irvine.

“This is the first bilingual, large-scale, emergency department-based, randomized clinical trial of its kind in the country focused on English- and Spanish-speaking Latino participants,” said lead author Dr. Federico Vaca, UCI professor of emergency medicine. “Our aim was to overcome well-known barriers to alcohol screening and intervention from the emergency department while ...

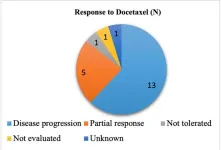

Value of chemotherapy post immunotherapy in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer

2023-06-07

“[...] large multicenter prospective randomized trials are needed to provide the clinical evidence for the use of [chemotherapy] in second line and third-line post [immunotherapy] failure.”

BUFFALO, NY- June 7, 2023 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 14 on May 26, 2023, entitled, “Value of chemotherapy post immunotherapy in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).”

Lung cancer is the number one cause of mortality among all types of cancer worldwide. Its ...

Pioneer of multicore processor design receives the ACM-IEEE CS Eckert-Mauchly Award

2023-06-07

ACM, the Association for Computing Machinery, today announced that Kunle Olukotun, a Professor at Stanford University, is the recipient of the ACM-IEEE CS Eckert-Mauchly Award for contributions and leadership in the development of parallel systems, especially multicore and multithreaded processors.

In the early 1990s, Olukotun became a leading designer of a new kind of microprocessor known as a “chip multiprocessor”—today called a “multicore processor.” His work demonstrated the performance advantages of multicore processors ...

Using genomics to unlock the full potential of industrial hemp

2023-06-07

Plant biologist Alex Harkess, PhD, and his lab at HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology are on a mission to change the future of food and fiber crops, one flowering plant species at a time. Much of plant breeding and global food production relies on the pollination of flowers to produce fruits that are eaten and used to produce further progeny. This process might sound straightforward, but it is actually complicated by the fact that some flowers contain only male or female reproductive organs, others contain both (hermaphrodites), and some can even switch sexes.

How flowers become male, ...

MD Anderson Research Highlights for June 7, 2023

2023-06-07

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Recent developments include a molecularly driven Phase I trial of the ATR inhibitor camonsertib, an artificial intelligence model to predict immunotherapy responses in lung cancer, an analysis of cognitive and functional outcomes following treatment ...

Comprehensive new report tackles food safety risks in the informal sector of developing countries

2023-06-07

Key messages

Despite ongoing structural changes, small-scale processors, grocers, market vendors and food service operators dominate the food systems of most low- and lower middle-income countries;

Unsafe food is widespread in informal food distribution channels, having national public health implications;

Very few countries have coherent strategies for tackling food safety risks in the informal sector;

Most of the policy attention and resources now devoted to domestic food safety in the developing world focuses on strengthening ...

Exposure to “forever chemicals” during pregnancy linked to increased risk of obesity in kids

2023-06-07

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The risks of exposure to “forever chemicals” start even before birth, a new study confirms, potentially setting up children for future health issues.

Exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) during pregnancy was linked to slightly higher body mass indices and an increased risk of obesity in children, according to a new Environmental Health Perspectives study led by Brown University researchers.

While this link has been suggested in previous research, the data has been inconclusive. The new study, which was funded by the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes program ...

Parker Solar Probe flies into the fast solar wind and finds its source

2023-06-07

NASA's Parker Solar Probe (PSP) has flown close enough to the sun to detect the fine structure of the solar wind close to where it is generated at the sun's surface, revealing details that are lost as the wind exits the corona as a uniform blast of charged particles.

It's like seeing jets of water emanating from a showerhead through the blast of water hitting you in the face.

In a paper to be published this week in the journal Nature, a team of scientists led by Stuart D. Bale, a professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, and James Drake of the University of Maryland-College ...

Use of wearable devices in individuals with or at risk for cardiovascular disease

2023-06-07

About The Study: Among individuals with or at risk for cardiovascular disease, fewer than 1 in 4 use wearable devices, with only half of those reporting consistent daily use, according to the results of this study based on a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults in 2019 and 2020. As wearable devices emerge as tools that can improve cardiovascular health, the current use patterns could exacerbate disparities unless there are strategies to ensure equitable adoption.

Authors: Rohan Khera, M.D., M.S., of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, is the corresponding author.

To ...

What does ChatGPT say when you tell it you were sexually assaulted, you’re suicidal, or want to quit smoking?

2023-06-07

La Jolla, Calif. (June 5, 2023) — What does ChatGPT say when you tell it you were sexually assaulted, want to commit suicide, or are trying to quit smoking?

A new study published in JAMA Network Open led by John W. Ayers, Ph.D., from the Qualcomm Institute within the University of California San Diego, provides an early look into how artificially intelligent (AI) assistants could help answer public health questions.

Already, hundreds of millions use AI assistants like ChatGPT, and it will change the way the public accesses information. Given the growth of AI assistant use, the scientific team evaluated ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tiny flows, big insights: microfluidics system boosts super-resolution microscopy

Pennington Biomedical researcher publishes editorial in leading American Heart Association journal

New tool reveals the secrets of HIV-infected cells

HMH scientists calculate breathing-brain wave rhythms in deepest sleep

Electron microscopy shows ‘mouse bite’ defects in semiconductors

Ochsner Children's CEO joins Make-A-Wish Board

Research spotlight: Exploring the neural basis of visual imagination

Wildlife imaging shows that AI models aren’t as smart as we think

Prolonged drought linked to instability in key nitrogen-cycling microbes in Connecticut salt marsh

Self-cleaning fuel cells? Researchers reveal steam-powered fix for ‘sulfur poisoning’

Bacteria found in mouth and gut may help protect against severe peanut allergic reactions

Ultra-processed foods in preschool years associated with behavioural difficulties in childhood

A fanged frog long thought to be one species is revealing itself to be several

Weill Cornell Medicine selected for Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award

Largest high-precision 3D facial database built in China, enabling more lifelike digital humans

SwRI upgrades facilities to expand subsurface safety valve testing to new application

Iron deficiency blocks the growth of young pancreatic cells

Selective forest thinning in the eastern Cascades supports both snowpack and wildfire resilience

A sea of light: HETDEX astronomers reveal hidden structures in the young universe

Some young gamers may be at higher risk of mental health problems, but family and school support can help

Reduce rust by dumping your wok twice, and other kitchen tips

High-fat diet accelerates breast cancer tumor growth and invasion

Leveraging AI models, neuroscientists parse canary songs to better understand human speech

Ultraprocessed food consumption and behavioral outcomes in Canadian children

The ISSCR honors Dr. Kyle M. Loh with the 2026 Early Career Impact Award for Transformative Advances in Stem Cell Biology

The ISSCR honors Alexander Meissner with the 2026 ISSCR Momentum Award for exceptional work in developmental and stem cell epigenetics

The ISSCR honors stem cell COREdinates and CorEUstem with the 2026 ISSCR Public Service Award

Minimally invasive procedure effectively treats small kidney cancers

SwRI earns CMMC Level 2 cybersecurity certification

Doctors and nurses believe their own substance use affects patients

[Press-News.org] Calculation shows why heavy quarks get caught up in the flowNew results will help physicists interpret experimental data from particle collisions at RHIC and the LHC and better understand the interactions of quarks and gluons