(Press-News.org) Cephalopods are a large family of marine animals that includes octopuses, cuttlefish and squid. They live in every ocean, from warm, shallow tropical waters to near-freezing, abyssal depths. More remarkably, report two scientists at University of California San Diego in a new study, at least some cephalopods possess the ability to recode protein motors within cells to adapt “on the fly” to different water temperatures.

Writing in the June 8, 2023 edition of Cell, first author Kavita J. Rangan, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of senior author Samara L. Reck-Peterson, PhD, a professor in the departments of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Cell and Developmental Biology at UC San Diego and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, describe how opalescent inshore squid (Doryteuthis opalescens) employ RNA recoding to change amino acids at the protein level, improving the function of molecular motors that carry out diverse functions within cells in colder waters.

RNA recoding allows organisms to edit genetic information from the genomic blueprint to create new proteins. The process is rare in humans but is common in soft-bodied cephalopods, such as D. opalescens, which makes seasonal spawning migrations along the coast of San Diego.

“Cephalopods like D. opalescens are remarkable for their large nervous systems, body innovations and complex behaviors” said Rangan, “and their extensive use of RNA recoding has raised many questions about how this process might be involved in responding to environmental cues like temperature.”

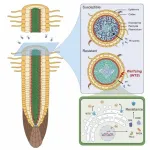

In the new study, Rangan and Reck-Peterson looked at changes to a pair of proteins in squid cells that serve as molecular motors transporting a variety of intracellular cargoes along cellular highways called microtubules. Specifically, the researchers focused on molecular motor proteins called kinesin and dynein, both of which are fundamental to transportation within all cells, including neurons. In humans, mutations in both motors are linked to neurodegenerative diseases.

Working with live squid hatchlings at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Rangan found that recoding of kinesin increased in animals as they experienced colder ocean water temperatures. Rangan then recreated recoded kinesin proteins using recombinant DNA technology and biochemistry. She then measured the movement of single motor molecules using advanced light microscopy and found that the recoded kinesin motors functioned better at cold temperatures.

“The work suggests that squid can tune their proteome (an organism’s entire complement of proteins) on the fly in response to changes in ocean temperature,” said Reck-Peterson. “One can speculate that this allows these marine ectotherms — animals that depend on external sources of body heat — to survive and thrive in a broad range of ocean temperatures.”

The scientists also found that RNA recoding varied across tissues, generating new kinesin variants with distinct movement properties.

“This work supports the idea that recoding in cephalopods is important for dynamically tuning protein function to support physiological needs and acclimate to changing environmental conditions” said Reck-Peterson. “These animals are taking a completely unique approach to adapting to their surroundings.”

Rangan said the findings also suggest the squid “editome” may be a valuable resource for highlighting regions of molecules that are amenable to plasticity or change. She is currently developing a database that includes the entire squid editome across different ocean temperatures.

“In highly conserved proteins, like kinesin and dynein, cephalopod recoding sites can point to overlooked residues of functional significance, said Rangan, “and this has broader implications for understanding basic protein function as well as for engineering proteins with specific functions. Cephalopods may be able to show us where to look and what changes to make.”

END

When water temperatures change, the molecular motors of cephalopods do too

RNA recoding is widespread in some animals, though not humans; UC San Diego researchers report squid employ it to dynamically alter key proteins to work better in colder water

2023-06-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A potential milestone in cancer therapy

2023-06-08

Prostate cancer is the most common non-skin cancer in men worldwide. According to international estimates about one in six men will get prostate cancer during their lifetime and worldwide, over 375’000 patients will die from it each year. Tumor resistance to current therapies plays an essential role in this and new approaches are therefore urgently needed. Now an international research team from the University of Bern, Inselspital Bern and the University of Connecticut (USA) has identified a previously unknown weak spot in prostate cancer ...

Comparing doctors to peers doesn’t make them hate their jobs and may improve quality of care, new USC Schaeffer study finds

2023-06-08

June 8, 2023 — Showing people how their behavior compares to their peers is a commonly used method to improve behavior. But in the wake of a global pandemic that exacerbated health care providers’ job dissatisfaction and burnout, questions remain about the potentially negative effects of peer comparison on the well-being of clinicians.

A new study from the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics reveals fresh insights into the relationship between peer comparison and job satisfaction among clinicians. Published in JAMA Network Open, the study challenges prior findings that such feedback increases job dissatisfaction and burnout.

Researchers ...

Scientists discover how plants fight major root disease

2023-06-08

Researchers led by CHEN Yuhang and ZHOU Jianmin from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have shown how plants resist clubroot, a major root disease that threatens the productivity of Brassica crops such as rape.

The study, which uncovers novel mechanisms underlying plant immunity and promises a new avenue for crop breeding, was published in Cell.

Clubroot, a soil-borne disease, is the most devastating disease of Brassica crops. In China, approximately 3.2–4 million hm2 of agricultural land is affected by clubroot each year, resulting in a 20%–30% yield ...

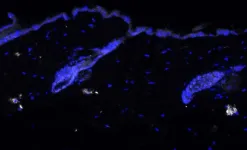

The IL-17 protein plays a key role in skin ageing

2023-06-08

A team of researchers from IRB Barcelona and CNAG identifies the IL-17 protein as a determining factor in skin ageing.

Blocking the function of IL-17 reduces the pro-inflammatory state and delays the appearance of age-related features in the skin.

Published in the journal Nature Aging, the work opens up new perspectives in the development of therapies to improve skin ageing health.

A team of scientists from the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) in collaboration with the National ...

University of Cincinnati study examines role of metabolites in disease treatment

2023-06-08

Each year, about 200,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with a bulge in the lower part of the aorta, the main artery in the body, called an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

New research from the University of Cincinnati examines the role a particular metabolite plays in the development of AAA and could lead to the first treatment of the condition.

The research was published in the journal Circulation.

“We started the study by examining whether AAA patients themselves had an increase in trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). We examined an American and Swedish ...

Study unravels the mysteries of actin filament polarity

2023-06-08

Actin filaments — protein structures critical to living movement from single cells to animals — have long been known to have polarity associated with their physical characteristics, with growing “barbed” and shrinking “pointed” ends. The ends of the filament are also different in the way they interact with other proteins in cells. However, the mechanism that determines these differences has never been entirely clear to scientists. Now, researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have revealed key atomic structures of ...

Colorful foods improve athletes’ vision

2023-06-08

Nutrition is an important part of any top athlete’s training program. And now, a new study by researchers from the University of Georgia proposes that supplementing the diet of athletes with colorful fruits and vegetables could improve their visual range.

The paper, which was published in Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, examines how a group of plant compounds that build up in the retina, known as macular pigments, work to improve eye health and functional vision.

Previous studies done by UGA researchers Billy R. Hammond and ...

Research puts lens on a new vision for land use decision making

2023-06-08

A new framework for making better and more transparent decisions about the use of our land could help to balance society’s demands upon it with protecting and enhancing the environment.

Researchers led by the University of Leicester have proposed a framework for decisions on land use, from nationwide policymaking to building happening at street level, that would involve the most representative range of stakeholders, from those with financial interests in the land to the local communities who use it and more besides.

Now published in the journal People and Nature, it encourages decisionmakers ...

'Most horrible’ brain tumor patients falling through healthcare cracks, study shows

2023-06-08

Patients suffering from the “most horrible” rare brain tumour are falling through the cracks of mental health provision, University of Essex researchers have found.

A recent study which interviewed patients and clinicians discovered survivors struggle to access therapy available for other serious illnesses, such as cancer, and there was a lack of specialised support.

For the first time, the mental health of British rare brain tumour patients was examined by psychologists and now researchers are calling for urgent changes to the health service.

Dr Katie Daughters hopes her findings –published in ...

Discovering cell identity: $6 million NIH grant funds new Penn Medicine research to uncover cardiac cell development

2023-06-08

PHILADELPHIA— Historically, scientists have studied how cells develop and give rise to specialized cells, such as heart, liver, or skin cells, by examining specific proteins. However, it remains unclear how many of these proteins influence the activity of hundreds of genes at the same time to turn one cell type into another cell type. For example, as the heart develops, stem cells and other specialized cells will give rise to heart muscle cells, endothelial cells (lining of blood vessels), smooth muscle cells, and cardiac fibroblasts. But the details of this process remain mysterious.

As a result of a $6 million, seven-year ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Plants retain a ‘genetic memory’ of past population crashes, study shows

CPR skills prepare communities to save lives when seconds matter

FAU study finds teen ‘sexting’ surge, warns of sextortion and privacy risks

Chinese Guidelines for Clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Cirrhosis (2025)

Insilico Medicine featured in Harvard Business School case on Rentosertib

Towards unlocking the full potential of sodium- and potassium-ion batteries

UC Irvine-led team creates first cell type-specific gene regulatory maps for Alzheimer’s disease

Unraveling the mystery of why some cancer treatments stop working

From polls to public policy: how artificial intelligence is distorting online research

Climate policy must consider cross-border pollution “exchanges” to address inequality and achieve health benefits, research finds

What drives a mysterious sodium pump?

Study reveals new cellular mechanisms that allow the most common chronic cardiac arrhythmia to persist in the heart

Scientists discover new gatekeeper cell in the brain

High blood pressure: trained laypeople improve healthcare in rural Africa

Pitt research reveals protective key that may curb insulin-resistance and prevent diabetes

Queen Mary research results in changes to NHS guidelines

Sleep‑aligned fasting improves key heart and blood‑sugar markers

Releasing pollack at depth could benefit their long-term survival, study suggests

Addictive digital habits in early adolescence linked to mental health struggles, study finds

As tropical fish move north, UT San Antonio researcher tracks climate threats to Texas waterways

Rich medieval Danes bought graves ‘closer to God’ despite leprosy stigma, archaeologists find

Brexpiprazole as an adjunct therapy for cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia

Applications of endovascular brain–computer interface in patients with Alzheimer's disease

Path Planning Transformers supervised by IRRT*-RRMS for multi-mobile robots

Nurses can deliver hospital care just as well as doctors

From surface to depth: 3D imaging traces vascular amyloid spread in the human brain

Breathing tube insertion before hospital admission for major trauma saves lives

Unseen planet or brown dwarf may have hidden 'rare' fading star

Study: Discontinuing antidepressants in pregnancy nearly doubles risk of mental health emergencies

Bipartisan members of congress relaunch Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) Caucus with event that brings together lawmakers, medical experts, and patient advocates to address critical gap i

[Press-News.org] When water temperatures change, the molecular motors of cephalopods do tooRNA recoding is widespread in some animals, though not humans; UC San Diego researchers report squid employ it to dynamically alter key proteins to work better in colder water