(Press-News.org) The largest marine predator that ever lived was no cold-blooded killer.

Well, a killer, yes. But a new analysis by environmental scientists from UCLA, UC Merced and William Paterson University sheds light on the warm-blooded animal’s ability to regulate its body temperature — and might help explain why it went extinct.

After analyzing isotopes in the tooth enamel of the ancient shark, which went extinct about 3.6 million years ago, the scientists concluded the megalodon could maintain a body temperature that was about 13 degrees Fahrenheit (about 7 degrees Celsius) warmer than the surrounding water.

That temperature difference is greater than those that have been determined for other sharks that lived alongside the megalodon and is large enough to categorize megalodons as warm-blooded.

The paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that the amount of energy the megalodon used to stay warm contributed to its extinction. And it has implications for understanding current and future environmental changes.

“Studying the driving factors behind the extinction of a highly successful predatory shark like megalodon can provide insight into the vulnerability of large marine predators in modern ocean ecosystems experiencing the effects of ongoing climate change,” said lead researcher Robert Eagle, a UCLA assistant professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and member of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

Megalodons, which are believed to have reached lengths up to 50 feet, belonged to a group of sharks called mackerel sharks — members of that group today include the great white and thresher shark. While most fish are cold-blooded, with body temperatures that are the same as the surrounding water, mackerel sharks keep the temperature of all or parts of their bodies somewhat warmer than the water around them, qualities called mesothermy and regional endothermy, respectively.

Sharks store heat generated by their muscles, making them different from fully warm-blooded or endothermic animals like mammals. In mammals, a region of the brain called the hypothalamus regulates body temperature.

Various lines of evidence have hinted that megalodon might have been mesothermic. But without data from the soft tissues that drive body temperature in modern sharks, it has been difficult to determine if or to what extent megalodon was endothermic.

In the new study, the scientists looked for answers in the megalodon’s most abundant fossil remains: its teeth. A main component of teeth is a mineral called apatite, which contains atoms of carbon and oxygen. Like all atoms, carbon and oxygen can come in “light” or “heavy” forms known as isotopes, and the amount of light or heavy isotopes that make up apatite as it forms can depend on a range of environmental factors. So the isotopic composition of fossil teeth can reveal insights about where an animal lived and the types of foods it ate, and — for marine vertebrates — information like the chemistry of the seawater where the animal lived and the animal’s body temperature.

“You can think of the isotopes preserved in the minerals that make up teeth as a kind of thermometer, but one whose reading can be preserved for millions of years,” said Randy Flores, a UCLA doctoral student and fellow of the Center for Diverse Leadership in Science, who worked on the study. “Because teeth form in the tissue of an animal when it’s alive, we can measure the isotopic composition of fossil teeth in order to estimate the temperature at which they formed and that tells us the approximate body temperature of the animal in life.”

Because most ancient and modern sharks are unable to maintain body temperatures significantly higher than the temperature of surrounding seawater, the isotopes in their teeth reflect temperatures that deviate little from the temperature of the ocean. In warm-blooded animals, however, the isotopes in their teeth record the effect of body heat produced by the animal, which is why the teeth indicate temperatures that are warmer than the surrounding seawater.

The researchers hypothesized that any difference between the isotope values of the megalodon and those of other sharks that lived at the same time would indicate the degree to which the megalodon could warm its own body.

The researchers collected teeth from the megalodon and other shark contemporaries from five locations around the world, and analyzed them using mass spectrometers at UCLA and UC Merced. Using statistical modeling to estimate sea water temperatures at each site where teeth were collected, the scientists found that megalodons’ teeth consistently yielded average temperatures that indicated it had an impressive ability to regulate body temperature.

Its warmer body allowed megalodon to move faster, tolerate colder water and spread out around the world. But it was that evolutionary advantage that might have contributed to its downfall, the researchers wrote.

The megalodon lived during the Pliocene Epoch, which began 5.33 million years ago and ended 2.58 million years ago, and global cooling during that period caused sea level and ecological changes that the megalodon did not survive.

“Maintaining an energy level that would allow for megalodon’s elevated body temperature would require a voracious appetite that may not have been sustainable in a time of changing marine ecosystem balances when it may have even had to compete against newcomers such as the great white shark,” Flores said.

Project co-leader Aradhna Tripati, a UCLA professor of Earth, planetary and space sciences and a member of the Institute of Environment and Sustainability, said the scientists now plan to apply the same approach to studying other species.

“Having established endothermy in megalodon, the question arises of how frequently it is found in apex marine predators throughout geologic history,” she said.

END

Megalodon was no cold-blooded killer

A killer, yes. But analysis of tooth minerals reveals how the warm-blooded predator maintained its body temperature

2023-06-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UCalgary study provides insight into how an infectious parasite uses immune cells as a Trojan Horse

2023-06-26

University of Calgary researchers have discovered how Leishmania parasites hide within the body to cause Leishmaniasis. The tiny parasites are carried by infected sand flies. Considered a tropical disease, one to two million people in more than 90 countries are infected every year. Effects range from disfiguring skin ulcers to enlarged spleen and liver and even death.

This chronic disease has been difficult to detect in the early stages. Scientists realized that the parasite was somehow manipulating immune cells but this process had not been well understood.

“This is the first study that shows how the parasite stalls the process of regular ...

Poop and prey help researchers estimate that gray whales off Oregon Coast consume millions of microparticles per day

2023-06-26

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State University researchers estimate that gray whales feeding off the Oregon Coast consume up to 21 million microparticles per day, a finding informed in part by poop from the whales.

Microparticle pollution includes microplastics and other human-sourced materials, including fibers from clothing. The finding, just published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, is important because these particles are increasing exponentially and predicted to continue doing so in the coming decades, according to researchers Leigh Torres and Susanne Brander.

Microparticle pollution is a threat to the health of ...

A smarter way to monitor critical care patients

2023-06-26

Surgical and intensive care patients face a higher risk of death and longer hospital stays because they are susceptible to both hypotension and hemodynamic instability – or unstable blood flow.

These potential complications require round-the-clock monitoring of several cardiac functions by nurses and physicians, but there’s currently no singular, convenient device on the market that can measure the most vital aspects of a patient’s cardiovascular health.

Ramakrishna Mukkamala, professor of bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering, and Aman Mahajan, ...

DPDT anticancer activity in human colon cancer HCT116 cells

2023-06-26

“Altogether, our results show that DPDT preferentially targets HCT116 colon cancer cells likely through DNA topoisomerase I poisoning.”

BUFFALO, NY- June 26, 2023 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 14 on June 21, 2023, entitled, “Diphenyl ditelluride anticancer activity and DNA topoisomerase I poisoning in human colon cancer HCT116 cells.”

Diphenyl ditelluride (DPDT) is an organotellurium (OT) compound with pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, antigenotoxic and antimutagenic activities when applied at low concentrations. However, ...

Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging announces 2023 fellows

2023-06-26

Chicago, Illinois – The Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging recognized ten new SNMMI Fellows today during a plenary session at the society’s 2023 Annual Meeting, held June 24-27. The SNMMI Fellowship was established in 2016 to recognize distinguished service to the society as well as exceptional achievement in the field of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. It is among the most prestigious formal recognitions available to long-time SNMMI members.

In keeping with tradition, SNMMI’s 2022-23 president, Munir Ghesani, MD, FACNM, FACR, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, ...

Purdue-launched solid rocket motor-maker Adranos flies off with Anduril

2023-06-26

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – Adranos Inc., a Purdue-originated company that grew from a doctoral project into an impactful company, has been acquired by a major Costa Mesa, California-based defense products company, Anduril Industries.

Terms of the deal were settled, and the acquisition was announced on Sunday (June 25) in The Wall Street Journal that Anduril Industries is to purchase Adranos, manufacturer of solid rocket motors and maker of ALITEC, a high-performance solid rocket fuel that gives greater payload capacity, range and speed to launch systems.

“The success of Adranos is the latest manifestation ...

Webb makes first detection of crucial carbon molecule

2023-06-26

A team of international scientists has used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to detect a new carbon compound in space for the first time. Known as methyl cation (pronounced cat-eye-on) (CH3+), the molecule is important because it aids the formation of more complex carbon-based molecules. Methyl cation was detected in a young star system, with a protoplanetary disk, known as d203-506, which is located about 1,350 light-years away in the Orion Nebula.

Carbon compounds form the foundations of all known life, ...

Despite environmental trade-offs, dairy milk is a critical, low-impact link in global nutrition

2023-06-26

Philadelphia, June 26, 2023 – Along with all global sectors, the dairy industry is working to reduce its environmental impact as we look toward a shared 2050 net zero future. Research is currently focused on greenhouse gas mitigation strategies that do not compromise animal health and production, but many discussions maintain that a radical transformation—involving reducing animal-based foods and increasing plant-based foods—is needed in our agriculture production systems in order ...

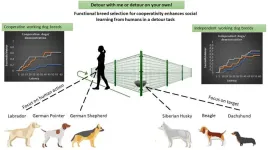

Would you detour with me? – Well, that depends on the dog breed!

2023-06-26

A new study from the Department of Ethology, Eötvös Loránd University, showed that dogs may not equally benefit from observing the ‘helpful action’ of a human demonstrator in the classic detour around a V-shaped fence task.

Those who are experienced with the world of ethological conferences, know all too well that if you present your work about dog behavior, the first (or second) question from the audience will be: “And did you check whether the breed of the dog had an effect on your results?”

Actually, this is not surprising as most people are familiar with the mindboggling variability of hundreds of ...

UCLA researchers uncover potential biomarkers of positive response to immunotherapy

2023-06-26

FINDINGS

Scientists at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified potential new biomarkers that could indicate how someone diagnosed with metastatic melanoma will respond to immunotherapy treatment.

The researchers found when T cells are activated, they release a protein called CXCL13, which helps attract more B cells and T cells to the tumor site. The B cells then show the T cells specific parts of the tumor, which leads to increased activation of the T cells and their ability to fight the cancer. This cooperation between T cells and B cells was associated with improved survival in patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Megalodon was no cold-blooded killerA killer, yes. But analysis of tooth minerals reveals how the warm-blooded predator maintained its body temperature