(Press-News.org) Two Georgia Tech researchers, Alex Robel and Shi Joyce Sim, have collaborated on a new model for how water moves under glaciers. The new theory shows that up to twice the amount of subglacial water that was originally predicted might be draining into the ocean – potentially increasing glacial melt, sea level rise, and biological disturbances.

The paper, published in Science Advances, “Contemporary Ice Sheet Thinning Drives Subglacial Groundwater Exfiltration with Potential Feedbacks on Glacier Flow”, is co-authored by Colin Meyer (Dartmouth), Matthew Siegfried (Colorado School of Mines), and Chloe Gustafson (USGS).

While there are pre-existing methods to understand subglacial flow, these techniques involve time-consuming computations. In contrast, Robel and Sim developed a simple equation, which can predict how fast exfiltration, the discharge of groundwater from aquifers under ice sheets, using satellite measurements of Antarctica from the last two decades.

“In mathematical parlance, you would say we have a closed form solution,” explains Robel, an assistant professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “Previously, people would run a hydromechanical model, which would have to be applied at every point under Antarctica, and then run forward over a long time period.” Since the researchers’ new theory is a mathematically simple equation, rather than a model, “the entirety of our prediction can be done in a fraction of a second on a laptop,” Robel says.

Robel adds that while there is precedence for developing these kinds of theories for similar kinds of models, this theory is specific in that it is for the particular boundary conditions and other conditions that exist underneath ice sheets. “This is, to our knowledge, the first mathematically simple theory which describes the exfiltration and infiltration underneath ice sheets.”

“It's really nice whenever you can get a very simple model to describe a process — and then be able to predict what might happen, especially using the rich data that we have today. It’s incredible” adds Sim, a research scientist in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “Seeing the results was pretty surprising.”

One of the main arguments in the paper underscores the potentially large source of subglacial water — possibly up to double the amount previously thought — that could be affecting how quickly glacial ice flows and how quickly the ice melts at its base. Robel and Sim hope that the predictions made possible by this theory can be incorporated into ice sheet models that scientists use to predict future ice sheet change and sea level rise.

A dangerous feedback cycle

Aquifers are underground areas of porous rock or sediment rich in groundwater. “If you take weight off aquifers like there are under large parts of Antarctica, water will start flowing out of the sediment,” Robel explains, referencing a diagram Sim created. While this process, known as exfiltration, has been studied previously, focus has been on the long time scales of interglacial cycles, which cover tens of thousands of years.

There has been less work on modern ice sheets, especially on how quickly exfiltration might be occurring under the thinning parts of the current-day Antarctic ice sheet. However, using recent satellite data and their new theory, the team has been able to predict what exfiltration might look like under those modern ice sheets.

“There's a wide range of possible predictions,” Robel explains. “But within that range of predictions there is the very real possibility that groundwater may be flowing out of the aquifer at a speed that would make it a majority, or close to a majority of the water that is underneath the ice sheet.”

If those parameters are correct, that would mean there's twice as much water coming into the subglacial interface than previous estimates assumed.

Ice sheets act like a blanket, sitting over the warm earth and trapping heat on the bottom, away from Antarctica’s cold atmosphere — and this means that the warmest place in the Antarctic ice sheet is at the bottom of a sheet, not on the surface. As an ice sheet thins, the warmer underground water can exfiltrate more readily, and this heat gradient can accelerate the melting that an ice sheet experiences.

“When the atmosphere warms up, it takes tens of thousands of years for that signal to diffuse through an ice sheet of the size of the thickness of the Antarctic ice sheet,” Robel explains. “But this process of exfiltration is a response to the already-ongoing thinning of the ice sheet, and it's an immediate response right now.”

Broad implications

Beyond sea level rise, this additional exfiltration and melt has other implications. Some of the places of richest marine productivity in the world occur off the coast of Antarctica, and being able to better predict exfiltration and melt could help marine biologists better understand where marine productivity is occurring, and how it might change in the future.

Robel also hopes this work will open the doorway to more collaborations with groundwater hydrologists who may be able to apply their expertise to ice sheet dynamics, while Sim underscores the need for more fieldwork.

“Getting the experimentalists and observationalists interested in trying to help us better constrain some of the properties of these water-laden sediments — that would be very helpful,” Sim says. “That's our largest unknown at this point, and it heavily influences the results.”

“It's really interesting how there's a potential to draw heat from deeper in the system,” she adds. “There's quite a lot of water that could be drawing more heat out, and I think that there's a heat budget there that could be interesting to look at.”

Moving forward, collaboration will continue to be key. “I really enjoyed talking to Joyce (Sim) about these problems,” Rober says, “because Joyce is an expert on heat flow and porous flow in the Earth's interior, and those are problems that I had not worked on before. That was kind of a nice aspect of this collaboration. We were able to bridge these two areas that she works on and that I work on.”

By: Selena Langner

END

Thinning ice sheets may drive sharp rise in subglacial waters

A new theory shows how water underneath glaciers may surge — creating a dangerous feedback cycle.

2023-08-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New research finds way to reduce bias in children

2023-08-21

Children’s views of inequality may be influenced by how its causes are explained to them, finds a new study by a team of psychology researchers. The work offers insights into the factors that affect how larger social issues are perceived at a young age and points to new ways to reduce bias toward lower-status economic groups.

“When making sense of social inequalities, adults may consider the structural forces at play—for example, people may cite policies related to legacy admissions when thinking about how disparities first arise,” says Rachel Leshin, a New York University doctoral student and the lead ...

It all depends on the genetic diversity

2023-08-21

Plants are not exposed to herbivores without defenses. When an insect feeds on a leaf, thereby wounding it and releasing oral secretions, a signaling cascade is elicited in the plant, usually starting with a rapid increase in the amount of the plant hormone jasmonic acid and its active isoleucine conjugate. Jasmonic acid regulates various reactions in plants, including defenses against herbivores and responses to environmental stress.

Mutants with disadvantageous properties do not necessarily disappear

An important thesis of evolutionary theory is natural selection and the conclusion that mutants with disadvantageous properties disappear ...

UArizona Valley fever expert Galgiani to receive lifetime achievement award

2023-08-21

The Arizona Bioindustry Association announced that renowned Valley fever researcher John Galgiani, MD, professor and director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, is the 2023 recipient of the AZBio Pioneer Award for Lifetime Achievement.

The Pioneer Award is the highest honor awarded by Arizona’s bioscience community and is extended to an Arizonan whose body of work has made life better for people at home and around the world. Galgiani’s four decades of Valley fever research, ...

University breaks ground on one-of-a-kind semiconductor facility

2023-08-21

The University of Arkansas celebrated an important milestone with the groundbreaking on a building that Chancellor Charles Robinson suggested might someday rival the U of A’s most iconic structure, Old Main, in significance to the university and the state of Arkansas.

Robinson and other university leaders, including University of Arkansas System President Don Bobbitt and members of the U of A System Board of Trustees, as well as researchers and industry leaders, gathered at the Arkansas Research and Technology Park in South Fayetteville to celebrate construction of the national Multi-User Silicon Carbide ...

Do prisons hold the key to solving the opioid crisis?

2023-08-21

With opioid overdose deaths surging in the United States, many communities are in desperate need of solutions to bring down the body count. Among the most promising is strengthening prison reentry programs for highest-risk users, a Rutgers-led study has found.

“For people who use drugs and have been in prison for several years, the reentry period can be chaotic and disorienting,” said Grant Victor, an assistant professor in the Rutgers School of Social Work and lead author of the study published in the Journal of Offender Rehabilitation.

“Closing ...

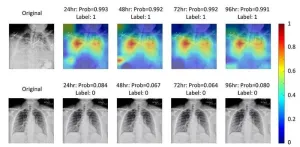

AI to predict critical care for patients with COVID-19

2023-08-21

The COVID-19 pandemic dealt a huge blow to healthcare systems and highlighted their major shortcomings. As of June 2023, there have been over 760 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, with almost 7 million deaths worldwide. During the major COVID-19 outbreaks, hospitals often had their intensive care units (ICU) running at full capacity for providing invasive mechanical ventilation to patients who were diagnosed as positive for COVID-19. These ICUs often operated with insufficient staff and intubation equipment.

One way to mitigate such problems is to accurately predict the prognosis ...

Simple blood test may predict future heart, kidney risk for people with Type 2 diabetes

2023-08-21

Research Highlights:

An analysis of a clinical trial of more than 2,500 people with Type 2 diabetes and kidney disease found that high levels of four biomarkers are strongly predictive for the development of heart and kidney issues.

People who took canagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2 inhibitor), had lower levels of the four biomarkers compared to those who took a placebo over the three-year study period.

Treatment with canagliflozin helped to substantially reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure and other heart complications among patients considered to have the highest risk.

Embargoed until 1 p.m. CT/2 p.m. ET Monday, ...

Listening for “sounds” from the far corners of space

2023-08-21

Scientists spectacularly confirmed the existence of gravitational waves several years ago, but now they are searching the cosmos for new and different types of these waves that result from different objects in deep space.

Benjamin Owen, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Texas Tech University, was recently awarded a three-year National Science Foundation (NSF) grant that aims to uncover and confirm additional types of gravitational waves.

“So far with gravitational waves we’ve seen what happens when you have ...

Agrela Ecosystems ignites innovation in data-driven agriculture

2023-08-21

ST. LOUIS, MO, August 21, 2023 – Agrela Ecosystems, a startup launched by Nadia Shakoor, PhD, principal investigator, at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center announced the pilot launch of its flagship product, PheNodeTM. This milestone marks the first step towards a full-scale commercial release set for 2025. PheNode is an advanced, scalable environmental sensor platform designed to empower users with customizable data collection and the rapid integration of new technologies. Already creating a buzz, the platform is now collecting data and generating customer feedback, ...

PS gene-editing shown to restore neural connections lost in brain disorder

2023-08-21

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (08/21/2023) — A new study from the University of Minnesota is the first to demonstrate the ability for gene therapy to repair neural connections for those with the rare genetic brain disorder known as Hurler syndrome. The findings suggest the use of gene therapies — an entirely new standard for treatment — for those with brain disorders like Hurler syndrome, which have a devastating impact on those affected.

The study was published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.

Hurler syndrome, also known as mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I), is a genetic disorder affecting newborns ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

[Press-News.org] Thinning ice sheets may drive sharp rise in subglacial watersA new theory shows how water underneath glaciers may surge — creating a dangerous feedback cycle.