A new Northwestern University-led study is changing the way astrophysicists understand the eating habits of supermassive black holes.

While previous researchers have hypothesized that black holes eat slowly, new simulations indicate that black holes scarf food much faster than conventional understanding suggests.

The study will be published on Wednesday (Sept. 20) in The Astrophysical Journal.

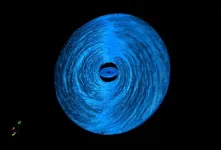

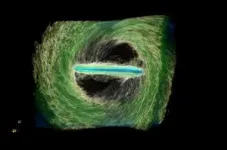

According to new high-resolution 3D simulations, spinning black holes twist up the surrounding space-time, ultimately ripping apart the violent whirlpool of gas (or accretion disk) that encircles and feeds them. This results in the disk tearing into inner and outer subdisks. Black holes first devour the inner ring. Then, debris from the outer subdisk spills inward to refill the gap left behind by the wholly consumed inner ring, and the eating process repeats.

One cycle of the endlessly repeating eat-refill-eat process takes mere months — a shockingly fast timescale compared to the hundreds of years that researchers previously proposed.

This new finding could help explain the dramatic behavior of some of the brightest objects in the night sky, including quasars, which abruptly flare up and then vanish without explanation.

“Classical accretion disk theory predicts that the disk evolves slowly,” said Northwestern’s Nick Kaaz, who led the study. “But some quasars — which result from black holes eating gas from their accretion disks — appear to drastically change over time scales of months to years. This variation is so drastic. It looks like the inner part of the disk — where most of the light comes from — gets destroyed and then replenished. Classical accretion disk theory cannot explain this drastic variation. But the phenomena we see in our simulations potentially could explain this. The quick brightening and dimming are consistent with the inner regions of the disk being destroyed.”

Kaaz is a graduate student in astronomy at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and member of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA). Kaaz is advised by paper co-author Alexander Tchekhovskoy, an associate professor of physics and astronomy at Weinberg and a CIERA member.

Mistaken assumptions

Accretion disks surrounding black holes are physically complicated objects, making them incredibly difficult to model. Conventional theory has struggled to explain why these disks shine so brightly and then abruptly dim — sometimes to the point of disappearing completely.

Previous researchers have mistakenly assumed that accretion disks are relatively orderly. In these models, gas and particles swirl around the black hole — in the same plane as the black hole and in the same direction of the black hole’s spin. Then, over a time scale of hundreds to hundreds of thousands of years, gas particles gradually spiral into the black hole to feed it.

“For decades, people made a very big assumption that accretion disks were aligned with the black hole’s rotation,” Kaaz said. “But the gas that feeds these black holes doesn’t necessarily know which way the black hole is rotating, so why would they automatically be aligned? Changing the alignment drastically changes the picture.”

The researchers’ simulation, which is one of the highest-resolution simulations of accretion disks to date, indicates that the regions surrounding the black hole are much messier and more turbulent places than previously thought.

More like a gyroscope, less like a plate

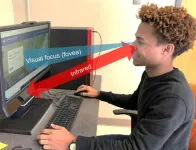

Using Summit, one of the world’s largest supercomputers located at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the researchers carried out a 3D general relativistic magnetohydrodynamics (GRMHD) simulation of a thin, tilted accretion disk. While previous simulations were not powerful enough to include all the necessary physics needed to construct a realistic black hole, the Northwestern-led model includes gas dynamics, magnetic fields and general relativity to assemble a more complete picture.

“Black holes are extreme general relativistic objects that affect space-time around them,” Kaaz said. “So, when they rotate, they drag the space around them like a giant carousel and force it to rotate as well — a phenomenon called ‘frame-dragging.’ This creates a really strong effect close to the black hole that becomes increasingly weaker farther away.”

Frame-dragging makes the entire disk wobble in circles, similar to how a gyroscope precesses. But the inner disk wants to wobble much more rapidly than the outer parts. This mismatch of forces causes the entire disk to warp, causing gas from different parts of the disk to collide. The collisions create bright shocks that violently drive material closer and closer to the black hole.

As the warping becomes more severe, the innermost region of the accretion disk continues to wobble faster and faster until it breaks apart from the rest of the disk. Then, according to the new simulations, the subdisks start evolving independently from one another. Instead of smoothly moving together like a flat plate surrounding the black hole, the subdisks independently wobble at different speeds and angles like the wheels in a gyroscope.

“When the inner disk tears off, it will precess independently,” Kaaz said. “It precesses faster because it’s closer to the black hole and because it’s small, so it’s easier to move.”

‘Where the black hole wins’

According to the new simulation, the tearing region — where the inner and outer subdisks disconnect — is where the feeding frenzy truly begins. While friction tries to keep the disk together, the twisting of space-time by the spinning black hole wants to rip it apart.

“There is competition between the rotation of the black hole and the friction and pressure inside the disk,” Kaaz said. “The tearing region is where the black hole wins. The inner and outer disks collide into each other. The outer disk shaves off layers of the inner disk, pushing it inwards.”

Now the subdisks intersect at different angles. The outer disk pours material on top of the inner disk. This extra mass also pushes the inner disk toward the black hole, where it is devoured. Then, the black hole’s own gravity pulls gas from the outer region toward the now-empty inner region to refill it.

The quasar connection

Kaaz said these fast cycles of eat-refill-eat potentially explain so-called “changing-look” quasars. Quasars are extremely luminous objects that emit 1,000 times more energy than the entire Milky Way’s 200 billion to 400 billion stars. Changing-look quasars are even more extreme. They appear to turn on and off over the duration of months — a tiny amount of time for a typical quasar.

Although classical theory has posed assumptions for how quickly accretion disks evolve and change brightness, observations of changing-look quasars indicate that they actually evolve much, much faster.

“The inner region of an accretion disk, where most of the brightness comes from, can totally disappear — really quickly over months,” Kaaz said. “We basically see it go away entirely. The system stops being bright. Then, it brightens again and the process repeats. Conventional theory doesn’t have any way to explain why it disappears in the first place, and it doesn’t explain how it refills so quickly.”

Not only do the new simulations potentially explain quasars, they also could answer ongoing questions about the mysterious nature of black holes.

“How gas gets to a black hole to feed it is the central question in accretion-disk physics,” Kaaz said. “If you know how that happens, it will tell you how long the disk lasts, how bright it is and what the light should look like when we observe it with telescopes.”

The study, “Nozzle shocks, disk tearing and streamers drive rapid accretion in 3D GRMHD simulations of warped thin disks,” was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.

END