(Press-News.org) Patients who quit smoking after undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for narrowed arteries have similar outcomes as non-smokers during four years of follow-up after the procedure, according to a large study published in the European Heart Journal [1] today (Wednesday). However, if they had been heavy, long-term smokers, no improvement was seen.

The study of 74,471 patients who had a PCI between 2009 and 2016 is the first, large population-based study to examine the impact of smoking on cardiovascular outcomes, such as death, heart attacks, and strokes, since drug-eluting stents (DES) were first approved for use in PCIs in Europe in 2002 and in the USA in 2003.

A DES is a short wire mesh tube that is inserted into the narrowed artery during PCI and is left in place permanently to allow blood to flow freely. It blocks cell proliferation by releasing a drug over a period of time. This prevents scarring which could narrow the stented artery. PCIs are often performed as an emergency treatment after a heart attack, or when there is a need to enhance blood flow in the coronary arteries, such as when chest pains (angina) can no longer be controlled with medication.

The researchers, led by Professor Jung-Kyu Han, from Seoul National University Hospital, South Korea, analysed data from the Korean National Health Insurance System nationwide database to investigate patient outcomes over four years following PCI. They looked at the rates of heart attacks, strokes, repeated procedures to widen arteries, and deaths from any cause. These are commonly called MACCE (major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events).

As well as collecting information on factors that could affect the results, such as age, sex, diabetes, blood pressure, alcohol drinking, exercise, body mass index (BMI), medications and socioeconomic status, they also gathered information on whether or not the patients were current smokers, never-smokers, or ex-smokers.

During four years of follow-up, current smokers had a 19.8% higher rate of MACCE than people who had never smoked, and ex-smokers had a comparable rate as never-smokers.

Additionally, they also analysed data from 31,887 patients with information on their smoking habits before and after PCI to further assess the impact of quitting smoking after PCI. They assessed how much patients smoked by placing them in four groups: less than 10 pack years, between 10 and 19 pack years, between 20 and 29 pack years, and over 30 pack years. ‘Pack years’ indicates a person’s accumulated exposure to tobacco; this was reached by multiplying the number of cigarettes smoked a day by the number of years the person had smoked.

Quitters who stopped smoking after PCI and who had smoked less than 20 pack years had a comparable rate of MACCE as people who had never smoked. However, those who had smoked more than 20 pack years before quitting had a 20% higher rate of MACCE, similar to the rate for persistent smokers.

Prof. Han said: “Patients who quit smoking after undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, with a cumulative smoking exposure of 20 pack years, had cardiovascular risks similar to those of non-smokers. Notably, this finding was observed within a relatively short interval after smoking cessation – a median of 628 days between pre- and post-PCI-health check-ups.”

One of the reasons Prof. Han and his colleagues conducted the study was because most previous research did not consider changes in smoking habits before and after PCI, leaving the effects of quitting smoking after PCI largely unexplored.

He said: “From the beginning of this study, my colleagues and I, as clinical researchers, suspected that there could be a threshold for irreversible harm resulting from smoking. Yet, the revelation that this threshold lies around 20 pack years – not like just five or 10 pack years – was an encouraging discovery. It suggests that smokers undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, who have not reached a cumulative smoking exposure of 20 pack years, may still have an opportunity to evade the lasting detrimental effects on their cardiovascular outcomes caused by smoking.

“Patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention should be encouraged to quit smoking as soon as possible, and smoking cessation may improve their cardiovascular outcomes even within a relatively short period of time. This emphasises the paramount importance of clinicians’ attention to their patients’ smoking status, along with the combined efforts of clinicians, patients, and policymakers in promoting smoking cessation.”

The study also contributes to de-bunking what is known as the “smokers’ paradox”; some previous studies seemed to suggest that smokers who had a heart attack had a better prognosis after PCI.

“A subgroup analysis of our study, which included 28,266 patients with myocardial infarction, refuted this paradox by demonstrating that current smokers had a significantly higher rate of adverse cardiovascular events compared to non-smokers. Notably, the positive impact of smoking cessation in patients with myocardial infarction was not as pronounced as in the overall study population. This may be due to insufficient numbers of patients and events in the subgroup analyses, or because the synergistic effects of heart attack and smoking resulted in more irreversible damage to the myocardium,” said Prof. Han.

A strength of the study is that it’s based on the Korean National Health Insurance System, which covers 97% of the Korean population, and is one of the most comprehensive sources of data on people’s health. Limitations include: whether or not a person smoked and how much was self-reported in a questionnaire and may not reflect the true status; other, unknown factors might affect the findings; the findings cannot be generalised to all races; and pack years cannot differentiate between the impact of long-term smoking at low doses from short-term smoking at high doses.

(ends)

[1] “Smoking and cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a Korean study”, by You-Jeong Ki et al. European Heart Journal. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad616

END

The Keck School of Medicine of USC has received funding from the National Institutes of Health as part of a five-year, $50.3 million “multi-omics” study of human health and disease involving six sites. Researchers in the Multi-Omics for Health and Disease consortium will study fatty liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, asthma, chronic kidney disease, preeclampsia and other conditions, with a focus on underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

Throughout the study, researchers will use ...

Deep inside our cells—each one complete with an identical set of genes—a molecular machine known as PRC2 plays a critical role in determining which cells become heart cells, versus brain or muscle or skin cells.

When the machine is missing or broken, normal fetal development can’t occur. If it’s mutated, cells can grow uncontrollably, and cancer can arise—a fact that has made PRC2 a source of keen interest for drug developers.

New research by scientists at CU Boulder and Harvard Medical School offers an unprecedented ...

The vagus nerve, known for its role in ‘resting and digesting’, has now been found to have an important role in exercise, helping the heart pump blood, which delivers oxygen around the body.

Currently, exercise science holds that the ‘fight or flight’ (sympathetic) nervous system is active during exercise, helping the heart beat harder, and the ‘rest and digest’ (parasympathetic) nervous system is lowered or inactive. However, University of Auckland physiology Associate Professor Rohit Ramchandra says that this current understanding is based on indirect estimates and a number of assumptions their new study has ...

Peer reviewed / Review, analysis and opinion

Cancer is a leading cause of mortality in women and ranks in the top three causes of premature death (under age 70) in women in almost every country worldwide.

New analysis finds, of the 2.3 million women who die prematurely from cancer each year, 1.5 million lives could be saved through the elimination of exposures to key risk factors or via early detection and diagnosis, while a further 800 000 deaths could be prevented if all women could access optimal ...

The estimated prevalence of REDs varies by sport, ranging from 15% to 80%. The syndrome often goes unrecognised by athletes themselves, their coaches, and team clinicians, and may unwittingly be exacerbated by the ‘sports culture,’ because of the perceived short term gains on performance from intentionally or unintentionally limiting calorie intake, warns the Statement.

REDs was first recognised as a distinct entity by the IOC in a 2014 consensus statement. This latest consensus, informed by a panel of international experts, draws on key advances in REDs science ...

Policies designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have been effective, however more stringent regulations are needed to limit global warming to the Paris temperature goals, finds a new analysis by UCL researchers of international efforts to fight climate change.

The research, published in Annual Reviews of Environment and Resources, tracked the rate of greenhouse gas emissions over the last two decades against global efforts to reduce them. Since the early 2000s, governments around the world have enacted numerous regulations to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Over the same ...

Before SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 pandemic, there was the Zika virus epidemic, lasting from 2015 to 2016. The Zika virus can cause serious birth defects and abnormalities. During the epidemic, one of the most striking results of Zika virus in pregnant women was the increase in offspring with microcephaly or a head much smaller than expected, a condition that can result in abnormal brain development.

While the Zika virus epidemic has ended, future outbreaks are inevitable as most of the world’s population lives in areas where the Zika virus mosquito thrives. Researchers in the Aagaard Lab at Baylor College of Medicine ...

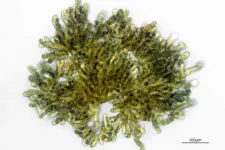

The cyanobacterium Aetokthonos hydrillicola produces not just one, but two highly potent toxins. In the latest issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), an international team led by Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and Freie Universität Berlin describes the second toxin, which had remained elusive until now. Even in low concentrations, it can destroy cells and is similar to substances currently used in cancer treatment. Two years ago, the same team established that the first toxin from the cyanobacterium is the cause of a mysterious disease among bald eagles in the USA.

Aetokthonos hydrillicola is ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. – Just about everyone knows that cigarette smoke is bad for babies. Should cooking fuels like natural gas, propane and wood be viewed similarly when used indoors?

That’s the takeaway from a new study led by University at Buffalo researchers, who looked at indoor air pollution exposure and early childhood development in a sample of more than 4,000 mother-child pairs in the U.S.

“Exposure to unclean cooking fuel and passive smoke during pregnancy and in early life are associated with developmental delays in ...

A University of Texas at Arlington researcher is working with a not-for-profit cooperative to develop and test a smart, automated cart that could replace humans who conduct fire hazard safety checks in nuclear power facilities.

Chan Kan, a UT Arlington assistant professor in the Department of Industrial, Manufacturing and Systems Engineering (IMSE), will lead the $250,000 project with the cooperative Utilities Service Alliance.

“We will develop and build a cart with state-of-the-art equipment that could replace human testing of nuclear facilities,” Kan said.

Currently, when the primary fire-sensing system fails or ...