(Press-News.org) Australian researchers at WEHI have found that a genetic change that increases the risk of inflammation, through a process described as ‘explosive’ cell death, is carried by up to 3% of the global population.

The study may explain why some people have an increased chance of developing conditions like inflammatory bowel disease or suffer more severe reactions to infections with bacteria like Salmonella.

At a glance

MLKL is a gene essential to triggering necroptotic cell death – a natural process that protects our body from infection. In some people this process can go awry and trigger severe tissue damage.

Study finds a genetic variation, known to enhance the ability of MLKL to kill cells, is carried by up to 3% of the global population.

The findings could lead to better personalised treatments for inflammation and other diseases in the future.

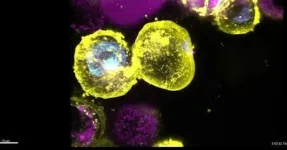

Immune power of ‘explosive’ cell death

Every minute, millions of cells in our bodies die on purpose. Cell death is an essential process that protects our bodies from disease by removing unwanted, damaged or dangerous cells, and preventing the spread of viruses, bacteria, and even cancer.

WEHI’s Dr Sarah Garnish is first author on the paper and said that while there are various types of cell death, necroptosis is distinguished by its ferocity – the cells essentially explode, which sounds an alarm for other cells in the body to respond.

“This is a good thing in the case of a viral infection, where necroptosis not only kills the infected cells but instructs the immune system to respond, clean things up, and start a more specific, long lived immune response,” Dr Garnish said.

“But when necroptosis is uncontrolled or excessive, the inflammatory response can actually trigger disease.”

Genetic brakes

The gatekeeper of necroptosis is the gene MLKL. When the body needs to trigger a cell death response with plenty of firepower, the cellular brakes that normally keep MLKL in-check are released. However, some of us make a form of MLKL with flimsy brakes.

Dr Garnish and her co-authors have been able to quantify this at a population level for the first time.

“For most of us, MLKL will stop when the body tells it to stop, but 2–3% of people have a form of MLKL that is less responsive to stop signals,” Dr Garnish said.

“While 2-3% doesn’t seem like much, when you consider the global population, this adds up to many millions of people carrying a copy of this gene variant.”

Project leader Dr Joanne Hildebrand said the research proposes that a common genetic change like this can combine with a person’s lifestyle, infection history and broader genetic makeup to increase the risk of inflammatory diseases and severe reactions to infections.

This is known as polygenic risk – the combined influence of multiple genes on developing a certain trait or condition.

“Taking Type 2 diabetes as an example, it’s rare that just one gene change determines whether someone will develop the condition,” Dr Hildebrand said.

“Instead many different genes play a role, as do environmental factors, like diet and smoking.”

Dr Hildebrand said it’s not as simple as directly connecting this difference in the MLKL gene with the chance of someone developing a specific condition.

“We haven’t tagged this MLKL gene variant to any one particular disease yet, but we see real potential for it to combine with other gene variants, and other environmental cues, to influence the intensity of our inflammatory response.”

Towards personalised medicine

Our understanding of MLKL has come a long way since it surfaced by chance in a WEHI lab more than 20 years ago. Today’s research opens the door for future tests and screening to determine disease risks.

Genome sequencing is becoming cheaper and more readily accessible. As more genomic data becomes available to researchers, it increases the likelihood that they can link common genetic variants, like the one described for MLKL, with disease.

In the future researchers hope to pinpoint the genetic changes that might mean someone is more likely to have a severe case of COVID-19, or less likely to bounce back after chemotherapy.

“Every piece of information like this helps us make personalised medicine more of a reality,” said Dr Garnish.

The WEHI team is also investigating whether uncontrolled necroptosis could be beneficial in some circumstances. For example, could people with the MLKL gene variant have a stronger cellular defensive response to certain viruses?

“Gene changes like this don’t usually accumulate in the population over time unless there is a reason for it – they generally get passed on because they do something good,” said Dr Garnish.

“We’re looking at the downsides of having this gene change, but we’re looking for the upsides as well.”

The study “A common human MLKL polymorphism confers resistance to negative regulation by phosphorylation” is now published in Nature Communications (DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-41724-6).

The research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Victorian State Government, the Australian Government Research Training Program Stipend Scholarship and the Wendy Dowsett Scholarship.

WEHI authors: Sarah Garnish, Katherine Martin, Maria Kauppi, Victoria Jackson, Shene Chiou, Yanxiang Meng, Daniel Frank, Emma Tovey, Komal Patel, Annette Jacobsen, Georgia Atkin-Smith, Ladina Di Rago, Marcel Doerflinger, Christopher Horne, Cathrine Hall, Samuel Young, Ian Wicks, Ashley Ng, Charlotte Slade, Andre Samson, John Silke, James Murphy and Joanne Hildebrand.

END

When cells go boom: study reveals inflammation-causing gene carried by millions

Researchers have found that a genetic change that increases the risk of inflammation, through a process described as ‘explosive’ cell death, is carried by up to 3% of the global population.

2023-10-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study from Fukushima shows even low doses of radiation may contribute to diabetes

2023-10-03

New research to be presented at this year’s Annual Meeting of The European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), Hamburg (2-6 Oct), suggests that exposure to low doses of radiation may contribute to an increased risk of diabetes.

The study by Dr Huan Hu and Dr Toshiteru Ohkubo from the Japanese National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health involved more than 6,000 out of around 20,000 emergency workers who responded to the radiation accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which was hit by a huge tsunami in March 2011.

Substantial amounts of radioactive materials were released into the environment following explosions at the ...

Worldwide audit finds testosterone replacement improves blood sugar control in men with type 2 diabetes

2023-10-03

Real-world data from an ongoing international audit of testosterone deficiency in men with type 2 diabetes, being presented at this year’s Annual Meeting of The European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), Hamburg (2-6 Oct), suggests that testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) improves glycaemic control for up to 2 years.

The early data from 37 centres across 8 countries who have so far joined the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) audit [1], suggest that the reason that HbA1c (a measure of average blood sugar levels over the past 2-3 months) continues ...

Semaglutide significantly improves blood sugar control and weight loss in adults with type 2 diabetes for up to 3 years in real-world study

2023-10-03

New research presented at this year’s Annual Meeting of The European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), Hamburg (2-6 Oct), shows that treatment with the drug semaglutide significantly improves blood sugar control and weight loss in adults with type 2 diabetes for up to three years.

“Our long-term analysis of semaglutide in a large and diverse cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes found a clinically relevant improvement in blood sugar control and weight loss after 6 months of treatment, comparable with that seen in randomised trials”, says Professor Avraham Karasik from the Institute of Research and Innovation at Maccabi Health Services ...

Drinking dark tea every day may help control blood sugar to reduce diabetes risk

2023-10-03

Drinking dark tea every day may help to mitigate type 2 diabetes risk and progression in adults through better blood sugar control, suggests new research at this year’s Annual Meeting of The European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), Hamburg (2-6 Oct).

The study, by researchers from the University of Adelaide in Australia and Southeast University in China, found that compared with never tea drinkers, daily consumers of dark tea had 53% lower risk for prediabetes and 47% reduced risk for type 2 diabetes, even after taking into account established risk factors known to drive the risk for diabetes, including age, ...

UC Riverside startup company wins prestigious NIH grant

2023-10-02

Soon after he joined UC Riverside in 2015, Maurizio Pellecchia, a professor of biomedical sciences in the UCR School of Medicine, began working with the UCR Research and Economic Development office to create on campus an incubator space. He envisioned that space as a home for UCR scientists to create startup companies to prove the commercial potential of their technologies. That multi-year effort helped create in the Multidisciplinary Research Building the EPIC Life Sciences Incubator that currently houses young companies in agricultural technology, biomedical technologies, bioengineering, and medicinal chemistry.

One of the tenant companies in the incubator ...

DNA from discarded whale bones suggests loss of genetic diversity due to commercial whaling

2023-10-02

Commercial whaling in the 20th century decimated populations of large whales but also appears to have had a lasting impact on the genetic diversity of today’s surviving whales, new research from Oregon State University shows.

Researchers compared DNA from a collection of whale bones found on beaches near abandoned whaling stations on South Georgia Island in the south Atlantic Ocean to DNA from whales in the present-day population and found strong evidence of loss of maternal DNA lineages among blue and humpback whales.

“A maternal lineage is often associated with an animal’s cultural memories such as feeding and breeding locations that are passed from one generation ...

Viruses dynamic and changing after dry soils are watered

2023-10-02

Viruses in soil may not be as destructive to bacteria as once thought and could instead act like lawnmowers, culling older cells and giving space for new growth, according to research out of the University of California, Davis, published Sept. 28 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

How viruses affect ecosystems, including bacteria, is challenging to untangle because they are complex and change over time and space. But the first annual rain on Mediterranean ecosystems, such as those in California, offers a kind of reset, triggering activity that can be observed.

Scientists ...

ACC Quality Summit explores practical strategies to reboot and rebrand health care quality

2023-10-02

The 2023 American College of Cardiology (ACC) Quality Summit kicks off on October 11-13 in Orlando, Florida, putting the spotlight on the value of ACC Accreditation and NCDR services to enhance health care quality. Cardiovascular clinicians and stakeholders across the U.S. will converge at this year’s Summit to discuss the role of accreditation and registries in health equity initiatives, best practices for rebooting and rebranding health care quality, and strategies to engage the CV team in the quality process.

“ACC’s ...

One in 3 adults with new-onset AFib occurring during hospitalization will have recurrent episode within a year

2023-10-02

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 2 October 2023

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

----------------------------

1. ...

Gene expression signatures of human senescent corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells

2023-10-02

“[...] our results from the RNA-Seq experiments show that senescent ocular surface cells, particularly SCj, have abnormal keratin expression patterns [...]”

A new priority research paper was published on the cover of Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 15, Issue 18, entitled, “Gene expression signatures of human senescent corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells.”

In this new study, researchers Koji Kitazawa, Akifumi Matsumoto, Kohsaku Numa, Yasufumi Tomioka, Zhixin A. Zhang, Yohei Yamashita, Chie Sotozono, Pierre-Yves Desprez, and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brain cells drive endurance gains after exercise

Same-day hospital discharge is safe in selected patients after TAVI

Why do people living at high altitudes have better glucose control? The answer was in plain sight

Red blood cells soak up sugar at high altitude, protecting against diabetes

A new electrolyte points to stronger, safer batteries

Environment: Atmospheric pollution directly linked to rocket re-entry

Targeted radiation therapy improves quality of life outcomes for patients with multiple brain metastases

Cardiovascular events in women with prior cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Transplantation and employment earnings in kidney transplant recipients

Brain organoids can be trained to solve a goal-directed task

Treatment can protect extremely premature babies from lung disease

Roberto Morandotti wins prestigious Max Born Award for pioneering research in quantum photonics

Scientists map brain's blood pressure control center

Acute coronary events registry provides insights into sex-specific differences

Bar-Ilan University and NVIDIA researchers improve AI’s ability to understand spatial instructions

New single-cell transcriptomic clock reveals intrinsic and systemic T cell aging in COVID-19 and HIV

Smaller fish and changing food webs – even where species numbers stay the same

Missed opportunity to protect pregnant women and newborns: Study shows low vaccination rates among expectant mothers in Norway against COVID-19 and influenza

Emotional memory region of aged brain is sensitive to processed foods

Neighborhood factors may lead to increased COPD-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations

Food insecurity impacts employees’ productivity

Prenatal infection increases risk of heavy drinking later in life

‘The munchies’ are real and could benefit those with no appetite

FAU researchers discover novel bacteria in Florida’s stranded pygmy sperm whales

DEGU debuts with better AI predictions and explanations

‘Giant superatoms’ unlock a new toolbox for quantum computers

Jeonbuk National University researchers explore metal oxide electrodes as a new frontier in electrochemical microplastic detection

Cannabis: What is the profile of adults at low risk of dependence?

Medical and materials innovations of two women engineers recognized by Sony and Nature

Blood test “clocks” predict when Alzheimer’s symptoms will start

[Press-News.org] When cells go boom: study reveals inflammation-causing gene carried by millionsResearchers have found that a genetic change that increases the risk of inflammation, through a process described as ‘explosive’ cell death, is carried by up to 3% of the global population.