Proteins are important molecules that perform a variety of functions essential to life. To function properly, many proteins must fold into specific structures. However, the way proteins fold into specific structures is still largely unknown. Researchers from the University of Tokyo developed a novel physical theory that can accurately predict how proteins fold. Their model can predict things previous models cannot. Improved knowledge of protein folding could offer huge benefits to medical research, as well as to various industrial processes.

You are literally made of proteins. These chainlike molecules, made from tens to thousands of smaller molecules called amino acids, form things like hair, bones, muscles, enzymes for digestion, antibodies to fight diseases, and more. Proteins make these things by folding into various structures that in turn build up these larger tissues and biological components. And by knowing more about this folding process, researchers can better understand more about the processes that constitute life itself. Such knowledge is also essential to medicine, not only for the development of new treatments and industrial processes to produce medicines, but also for knowledge of how certain diseases work, as some are examples of protein folding gone wrong. So, to say proteins are important is putting it mildly. Proteins are the stuff of life.

Encouraged by the importance of protein folding, Project Assistant Professor Koji Ooka from the College of Arts and Sciences and Professor Munehito Arai from the Department of Life Sciences and Department of Physics embarked on the hard task of improving upon the prediction methods of protein folding. This task is formidable for many reasons. In particular, the computational requirements to simulate the dynamics of molecules necessitate a powerful supercomputer. Recently, the artificial intelligence-based program AlphaFold 2 accurately predicts structures resulting from a given amino acid sequence; but it cannot give details of the way proteins fold, making it a black box. This is problematic, as the forms and behaviors of proteins vary such that two similar ones may fold in radically different ways. So, instead of AI, the duo needed a different approach: statistical mechanics, a branch of physical theory.

“For over 20 years, a theory called the Wako-Saitô-Muñoz-Eaton (WSME) model has successfully predicted the folding processes for proteins comprising around 100 amino acids or fewer, based on the native protein structures,” said Arai. “WSME can only evaluate small sections of proteins at a time, missing potential connections between sections farther apart. To overcome this issue, we produced a new model, WSME-L, where the L stands for ‘linker.’ Our linkers correspond to these nonlocal interactions and allow WSME-L to elucidate the folding process without the limitations of protein size and shape, which AlphaFold 2 cannot.”

But it doesn’t end there. There are other limitations of existing protein folding models that Ooka and Arai set their sights on. Proteins can exist inside or outside of living cells; those within are in some ways protected by the cell, but those outside cells, such as antibodies, require additional bonds during folding, called disulfide bonds, which help to stabilize them. Conventional models cannot factor in these bonds, but an extension to WSME-L called WSME-L(SS), where each S stands for sulfide, can. To further complicate things, some proteins have disulfide bonds before folding starts, so the researchers made a further enhancement called WSME-L(SSintact), which factors in that situation at the expense of extra computation time.

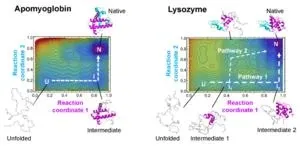

“Our theory allows us to draw a kind of map of protein folding pathways in a relatively short time; mere seconds on a desktop computer for short proteins, and about an hour on a supercomputer for large proteins, assuming the native protein structure is available by experiments or AlphaFold 2 prediction,” said Arai. “The resulting landscape allows a comprehensive understanding of multiple potential folding pathways a long protein might take. And crucially, we can scrutinize structures of transient states. This might be helpful for those researching diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s — both are caused by proteins which fail to fold correctly. Also, our method may be useful for designing novel proteins and enzymes which can efficiently fold into stable functional structures, for medical and industrial use.”

While the models produced here accurately reflect experimental observations, Ooka and Arai hope they can be used to elucidate the folding processes of many proteins that have not yet been studied experimentally. Humans have about 20,000 different proteins, but only around 100 have had their folding processes thoroughly studied.

###

Journal article: Koji Ooka and Munehito Arai. “Accurate prediction of protein folding mechanisms by simple structure-based statistical mechanical models”, Nature Communications, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-41664-1

Funding:

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP16H02217, JP19H02521, JP21K18841, and JP23H04545 (M.A.), Kayamori Foundation of Informational Science Advancement (M.A.), and a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows Grant Number JP20J11762 (K.O.).

Useful links:

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences - https://www.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/eng_site/

Department of Physics - https://www.phys.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/

Research contact:

Professor Munehito Arai

Department of Life Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences,

The University of Tokyo, 3-8-1 Komaba, Meguro, Tokyo 153-8902, Japan

arai@bio.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Press contact:

Mr. Rohan Mehra

Public Relations Group, The University of Tokyo,

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-8656, Japan

press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About The University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on Twitter at @UTokyo_News_en.

END