(Press-News.org) Images // Video

ANN ARBOR—For 200 years, scientists have failed to grow a common mineral in the laboratory under the conditions believed to have formed it naturally. Now, a team of researchers from the University of Michigan and Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan have finally pulled it off, thanks to a new theory developed from atomic simulations.

Their success resolves a long-standing geology mystery called the "Dolomite Problem." Dolomite—a key mineral in the Dolomite mountains in Italy, Niagara Falls, the White Cliffs of Dover and Utah's Hoodoos—is very abundant in rocks older than 100 million years, but nearly absent in younger formations.

"If we understand how dolomite grows in nature, we might learn new strategies to promote the crystal growth of modern technological materials," said Wenhao Sun, the Dow Early Career Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at U-M and the corresponding author of the paper published today in Science.

The secret to finally growing dolomite in the lab was removing defects in the mineral structure as it grows. When minerals form in water, atoms usually deposit neatly onto an edge of the growing crystal surface. However, the growth edge of dolomite consists of alternating rows of calcium and magnesium. In water, calcium and magnesium will randomly attach to the growing dolomite crystal, often lodging into the wrong spot and creating defects that prevent additional layers of dolomite from forming. This disorder slows dolomite growth to a crawl, meaning it would take 10 million years to make just one layer of ordered dolomite.

Luckily, these defects aren't locked in place. Because the disordered atoms are less stable than atoms in the correct position, they are the first to dissolve when the mineral is washed with water. Repeatedly rinsing away these defects—for example, with rain or tidal cycles—allows a dolomite layer to form in only a matter of years. Over geologic time, mountains of dolomite can accumulate.

To simulate dolomite growth accurately, the researchers needed to calculate how strongly or loosely atoms will attach to an existing dolomite surface. The most accurate simulations require the energy of every single interaction between electrons and atoms in the growing crystal. Such exhaustive calculations usually require huge amounts of computing power, but software developed at U-M's Predictive Structure Materials Science (PRISMS) Center offered a shortcut.

"Our software calculates the energy for some atomic arrangements, then extrapolates to predict the energies for other arrangements based on the symmetry of the crystal structure," said Brian Puchala, one of the software's lead developers and an associate research scientist in U-M's Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

That shortcut made it feasible to simulate dolomite growth over geologic timescales.

"Each atomic step would normally take over 5,000 CPU hours on a supercomputer. Now, we can do the same calculation in 2 milliseconds on a desktop," said Joonsoo Kim, a doctoral student of materials science and engineering and the study's first author.

The few areas where dolomite forms today intermittently flood and later dry out, which aligns well with Sun and Kim's theory. But such evidence alone wasn't enough to be fully convincing. Enter Yuki Kimura, a professor of materials science from Hokkaido University, and Tomoya Yamazaki, a postdoctoral researcher in Kimura's lab. They tested the new theory with a quirk of transmission electron microscopes.

"Electron microscopes usually use electron beams just to image samples," Kimura said. "However, the beam can also split water, which makes acid that can cause crystals to dissolve. Usually this is bad for imaging, but in this case, dissolution is exactly what we wanted."

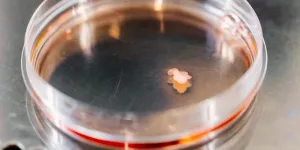

After placing a tiny dolomite crystal in a solution of calcium and magnesium, Kimura and Yamazaki gently pulsed the electron beam 4,000 times over two hours, dissolving away the defects. After the pulses, dolomite was seen to grow approximately 100 nanometers—around 250,000 times smaller than an inch. Although this was only 300 layers of dolomite, never had more than five layers of dolomite been grown in the lab before.

The lessons learned from the Dolomite Problem can help engineers manufacture higher-quality materials for semiconductors, solar panels, batteries and other tech.

"In the past, crystal growers who wanted to make materials without defects would try to grow them really slowly," Sun said. "Our theory shows that you can grow defect-free materials quickly, if you periodically dissolve the defects away during growth."

The research was funded by the American Chemical Society PRF New Doctoral Investigator grant, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science.

Study: Dissolution enables dolomite crystal growth near ambient conditions (DOI: 10.1126/science.adi3690)

END

'Dolomite Problem': 200-year-old geology mystery resolved

To build mountains from dolomite, a common mineral, it must periodically dissolve. This counter-intuitive lesson could help make new defect-free semiconductors and more.

2023-11-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AI recognizes the tempo and stages of embryonic development

2023-11-23

Animal embryos go through a series of characteristic developmental stages on their journey from a fertilized egg cell to a functional organism. This biological process is largely genetically controlled and follows a similar pattern across different animal species. Yet, there are differences in the details – between individual species and even among embryos of the same species. For example, the tempo at which individual embryonic stages are passed through can vary. Such variations in embryonic development are considered an important driver of evolution, as they can lead to new characteristics, thus promoting evolutionary adaptations and biodiversity.

Studying the embryonic ...

Potential new target and drug candidate for Barth syndrome

2023-11-23

In a Nature Metabolism paper published today, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh detail a potential new target and a small-molecule drug candidate for treating Barth syndrome, a rare, life-threatening and currently incurable genetic disease with devastating consequences.

Barth syndrome affects about 1 in every 300,000 to 400,000 babies born worldwide. Those with the condition have weak muscles and hearts and experience debilitating fatigue and recurrent infections.

Pitt researchers discovered that faulty mitochondria are at least partially to blame, and identified a molecular culprit that could be targeted to potentially reverse the disease course in the future.

In ...

New therapy can treat rare and hereditary diseases

2023-11-23

A lot of research has been done over many decades on diseases that are widespread in large parts of the population, such as cancer and heart disease. As a result, treatment methods have improved enormously thanks to long-term research efforts on diseases that affect many people.

However, there are many diseases that affect just a handful people. These diseases often fly under the radar and are far less researched. They include quite a few rare, hereditary diseases, such as DOOR syndrome, which is ...

Y-chromosome and its impact on digestive diseases

2023-11-23

A major breakthrough in human genetics has been achieved with the complete decoding of the human Y chromosome, opening up new avenues for research into digestive diseases. This milestone, along with advancements in third-generation sequencing technologies, is poised to revolutionize our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of digestive disorders and pave the way for more personalized and effective treatment strategies.

The Y chromosome, the smallest of the human chromosomes, has long been shrouded in mystery due to its complex repetitive structure. However, recent advancements in sequencing technologies have enabled researchers to unravel the intricate details of this genetic ...

Fractional COVID-19 booster vaccines produce similar immune response as full-doses

2023-11-23

Reducing the dose of a widely used COVID-19 booster vaccine produces a similar immune response in adults to a full-dose with fewer side effects, according to a new study.

The research, led by Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) and the National Centre for Communicable Diseases in Mongolia, found that a half dose of a Pfizer COVID-19 booster vaccine elicited a non-inferior immune response to a full dose in Mongolian adults who previously had AstraZeneca or Sinopharm COVID-19 shots. But it found half-dose boosting may be less effective in adults primed with the Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine.

The research ...

Consolidator Grants: ERC unleashes €627 million in grants to fuel excellent research across Europe

2023-11-23

Iliana Ivanova, European Commissioner for Innovation, Research, Culture, Education and Youth, said: “I extend my heartfelt congratulations to all the brilliant researchers who have been selected for ERC Consolidator Grants. I'm especially thrilled to note the significant increase in the representation of women among the winners for the third consecutive year in this prestigious grant competition. This positive trend not only reflects the outstanding contributions of women researchers but also highlights the strides we are making towards a more inclusive and diverse scientific community.”

President of the European Research Council Prof. Maria Leptin said: “The new ...

A fifth higher: Tropical cyclones substantially raise the Social Cost of Carbon

2023-11-23

Extreme events like tropical cyclones have immediate impacts, but also long-term implications for societies. A new study published in the journal Nature Communications now finds: Accounting for the long-term impacts of these storms raises the global Social Cost of Carbon by more than 20 percent, compared to the estimates currently used for policy evaluations. This increase is mainly driven by the projected rise of tropical-cyclone damages to the major economies of India, USA, China, Taiwan, and Japan under global warming.

“Intense tropical cyclones have the power to slow down the economic development of a country for more than a decade, our analysis shows. With global warming, the share ...

Study reveals how shipwrecks are providing a refuge for marine life

2023-11-23

An estimated 50,000 shipwrecks can be found around the UK’s coastline and have been acting as a hidden refuge for fish, corals and other marine species in areas still open to destructive bottom towed fishing, a new study has shown.

Many of these wrecks have been lying on the seabed for well over a century, and have served as a deterrent to fishers who use bottom towed trawling to secure their catches.

As a result, while many areas of the seabed have been damaged significantly in areas of heavy fishing pressure, the ...

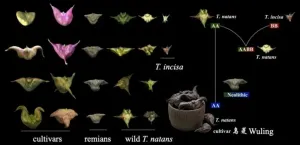

Pangenomic study of water caltrop — structural variations play a role in speciation and asymmetric subgenome evolution

2023-11-23

Rice, maize, and wheat provide more than half of the calories consumed by humans. The decrease in crop diversity poses a significant risk to global food security. Therefore, the utilization of orphan crops has become an effective approach to address food security crises. Nevertheless, in the face of rapid urban and rural modernization and the intensification of agricultural practices, the availability of wild and cultivated orphan crops is dwindling, with a noticeable disparity in their collection, preservation, ...

Professor Tao Jun's team at Yangzhou University analyses the molecular mechanism of PoWRKY71 in response to drought stress of Paeonia ostii

2023-11-23

Paeonia ostii is a widely grown woody crop with up to 40% α-linolenic acid in its seed oil, which is beneficial to human health. Drought is a major environmental factor limiting the popularisation of P. ostii in hilly and mountainous areas, which may affect plant growth or lead to plant death.WRKY is one of the largest families of transcription factors in plants, and plays an important role in plant response to drought stress. However, the molecular mechanism by which P. ostii WRKY transcription factors respond to drought stress is still unclear.

In September 2023, Horticulture ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

[Press-News.org] 'Dolomite Problem': 200-year-old geology mystery resolvedTo build mountains from dolomite, a common mineral, it must periodically dissolve. This counter-intuitive lesson could help make new defect-free semiconductors and more.