(Press-News.org) Ahab hunting down Moby Dick. Wile E. Coyote chasing the Road Runner. Learning Latin. Walking over hot coals. Standing in a long line for boba tea or entrance to a small, overpriced clothing retail store. Forking up for luxury nonsense.

What do these activities have in common? They’re all examples of the overvaluation of what economists call “sunk costs”: the price you’ve already irretrievably paid in time, money, effort, suffering or any combination of them for an item, an experience or a sense of self-esteem.

It’s a phenomenon we all recognize. It affects our behavior in ways that can be irrational. But we do it.

Here’s my story: My glacial-blue ’64 stick-shift Volvo station wagon had red, white and blue Colorado U.S. Bicentennial plates and a phalanx of three small bowling trophies for hood ornaments (I called it “the Bowlvo”). It was falling apart like a piece of overcooked chicken. (One day, I was shooting down Highway 25 in Colorado when the hood flew up in my face. Another time, as I was frantically downshifting into second gear while driving home at my usual unsafe speed on a winding mountain road, the shift lever came off in my hand.) I would have gone to the ends of the earth, or at least the end of my rope, to keep it in running condition. Or failing that, just to keep it.

For mysterious reasons, we are hardwired to value something more if we’ve put a lot of sweat equity — what we had to do to get (or in my case keep) that reward — into it. Neuroscientists are trying to figure out why we do that.

Shared stupidity

“We make fallacious decisions based on what we’ve invested in something, even if the probability of actually gaining an objective advantage from it is zero,” said assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral science Neir Eshel, MD, PhD. “And it’s not just us. This has been shown in animals across the animal kingdom.”

OK — all higher animals are hardwired to make dumb decisions. But why?

Blame dopamine: the “do it again, do it some more” brain chemical that’s been much talked about in connection with pleasure, learning and habit formation.

There’s a difference between wanting something and liking it, said Eshel, who focuses on how the brain motivates behavior. “You can want something very, very much even though you don’t even like it very much. Or vice versa.”

A few years ago, Eshel, his then-postdoctoral adviser Rob Malenka, MD, PhD, the Nancy Friend Pritzker Professor in Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, and some Stanford Medicine colleagues began conducting experiments to learn more about wanting versus liking and what, if any, role dopamine secretion in the brain plays in each of these states.

“We looked at how much an animal likes something — how much it will consume if that something is cost-free — and how much it wants something — how much that animal’s consumption is affected by the cost of getting it,” Eshel said.

The results of that experimentation are in a paper to be published Nov. 27 in Neuron.

The dopamine connection

In the course of their study, they came up with a possible neural mechanism for the longstanding psychological observation that we value rewards more if we worked harder for them: Dopamine release in the striatum, it turns out, is greatly influenced by the effort put forth to gain a reward.

“Now we may have found the neural basis for sunk cost,” Eshel said. “Dopamine could explain it.”

In their study of mice, the researchers defined “cost” as either the number of times the mice had to poke their noses into a hole in a box (anywhere between just once and nearly 50 times) or risk incurring mild to moderate foot shocks to get access to a “reward”: either sugar water or instant direct stimulation of dopamine release in two centers in a structure in the middle of the brain called the striatum. These centers are well known for their role in motivation and movement (motion), their abundance of dopamine receptors, and their innervation by dopamine-secreting tracts originating in regions deeper in the brain. And for their involvement in learning, habit formation and addiction.

The researchers first determined the test animals’ “cost-free consumption”: how much a mouse will consume until satiation in a cost-free situation (all it had to do was stick its nose in the hole, and bingo!). That told the investigators how much the mouse “liked” something.

Then, in steps, they raised the cost of acquisition by increasing the number of nose-pokes, or the intensity of electric shocks to a mouse’s feet, required to get the reward.

The researchers likewise methodically varied the amounts of reward (whether sucrose or direct stimulation of dopamine release in the striatum) animals got for a given amount of persistence or discomfort.

Dopamine release in mice’s striatum was assessed as soon as each reward was earned.

Not too surprisingly, striatal dopamine release was influenced by the size of the prize. But, the scientific team learned, raising the reward’s cost also triggered greater dopamine release in the striatum: There was a biochemical basis for the concept of sunk cost.

Sunk cost and survival

How does this make any evolutionary sense? To an economist, valuing something because of sunk costs is aberrant decision making.

One idea, Eshel suggested: “In an environment with limited resources (as most are), when we typically get rewarded only after really hard work, we may need high dopamine secretion to get us to do it again.”

“Because dopamine reinforces previous behaviors, it may reflect sunk costs,” he said. “The dopamine release we saw may enable you to pay those steep costs in the future.”

Maybe Eshel could have tested me instead. I know a thing or two about sunk costs.

I still miss the Bowlvo.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants K08MH123791 and P50DA04201), the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the Simons Foundation, and the Stanford Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END

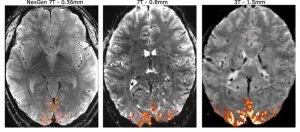

An intense international effort to improve the resolution of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for studying the human brain has culminated in an ultra-high resolution 7 Tesla scanner that records up to 10 times more detail than current 7T scanners and over 50 times more detail than current 3T scanners, the mainstay of most hospitals.

The dramatically improved resolution means that scientists can see functional MRI (fMRI) features 0.4 millimeters across, compared to the 2 or 3 millimeters typical of today's standard 3T fMRIs.

"The NexGen 7T scanner is a new tool that allows us to look at the brain circuitry underlying different diseases of the brain with ...

During the nearly five decades of its operation, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Hamburg has developed many fruitful collaborations with other scientific institutions located in the Hamburg metropolitan area. One example is the long-lasting collaboration between researchers at EMBL Hamburg and the Center for Biobased Solutions (CBBS) at the Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), which has recently yielded new insights into the structure and function of a lipid-degrading enzyme found in a microbe adapted to living in extreme conditions. The findings could help improve ...

The return of bluefin tuna to Northern European waters is a conservation success story, but rising sea temperatures in their Mediterranean nursery grounds mean this recovery may be short-lived, according to new research led by the University of Southampton.

Temperatures expected in the Mediterranean within the next 50 years are expected to drive juvenile tuna out of the Mediterranean, where they may be accidentally caught in existing sardine and anchovy fisheries – requiring fishery managers to adapt their methods to allow tuna nurseries to establish.

Outlining the research, published in Nature, lead author Clive Trueman, Professor of Geochemical Ecology ...

A new study published in the journal Gut has shed light on the complex relationship between serum lipids, lipid-modifying targets, and cholelithiasis, a common condition characterized by the formation of gallstones. The study, led by researchers at the First Hospital of Jilin University, employed a combination of observational and Mendelian randomization (MR) approaches to comprehensively assess these associations.

Cholelithiasis is a prevalent hepatobiliary disorder that primarily affects Western populations. It is a significant risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, ...

With images - the visual assets can be downloaded by clicking on this WeTransfer link:https://we.tl/t-mbRtSW5BzO

*See further information at end of release for captions and required pic credits

A Leeds researcher is keen to help beekeepers shape their practices following his study which appears to disprove the widespread belief that honeybees naturally insulate their colonies against the cold. His findings suggest that the creatures are potentially being subjected to thermally-induced ...

A large amount of the heavy automobile pollution from Copenhagen’s Bispeengbuen thoroughfare goes straight into people's homes. This, according to a study by researchers at the University of Copenhagen. A sensor developed by one of the researchers can help fill in the blanks of our understanding about local air pollution.

Air pollution cuts the lives of more than four thousand Danes short every year. Locally, we have a very limited understanding how many harmful substances waft in the air we breath. Indeed, air pollution is only monitored at fourteen locations across Denmark.

This ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Despite the many challenges they face, slightly more than half of unmarried low-income couples with children have positive co-parenting relationships, a new study found.

And those supportive relationships were linked to their children showing more empathy, less emotional insecurity and fewer behavior problems.

Parents who are good co-parents work together as a team, provide support to each other and back up each other’s parenting decisions, said Susan Yoon, lead author of the study and associate professor of social work at The Ohio State University.

Those types of relationships may be particularly hard for the parents in this study, ...

A common concern about gender-affirming hormone therapy for transmasculine people is the risk of red blood cell volume changes and erythrocytosis, a high concentration of red blood cells, with the use of prescribed testosterone. However, Mount Sinai researchers have found that testosterone treatment may be safer than previously reported, with results published today in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Mount Sinai researchers from the Division of Endocrinology and Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery examined the relationship between the use of testosterone as part ...

AMES, Iowa — During Orange City’s three-day tulip festival each May, the northwest Iowa town attracts roughly 40,000 visitors, more than six times its population. People come for the blooms and parades, traditional Dutch food and musical theater. For the community, it’s an opportunity to celebrate its cultural heritage and give a boost to local businesses.

Volunteers are essential to the festival’s success, as they are for many rural celebrations across the Midwest. But not a lot of research has examined their motivations. To help fill this gap, researchers surveyed hundreds of volunteers from 12 festivals — including ...

DANVERS, Mass. – Nov. 27, 2023 – Abiomed, part of Johnson & Johnson MedTech[1], announces the first patient in the world has been enrolled in the landmark RECOVER IV randomized controlled trial (RCT). The on-label, two-arm trial will randomize 548 patients to assess whether Impella support prior to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is superior to PCI without Impella in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) cardiogenic shock.

Impella is the only mechanical circulatory support device for the treatment of AMI cardiogenic ...