(Press-News.org) Heart disease kills 18 million people each year, but the development of new therapies faces a bottleneck: no physiological model of the entire human heart exists – so far. A new multi-chamber organoid that mirrors the heart’s intricate structure enables scientists to advance screening platforms for drug development, toxicology studies, and understanding heart development. The new findings, using heart organoid models developed by Sasha Mendjan’s group at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, are presented in the journal Cell on November 28.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, but only a few new therapies are on the horizon. Similarly, one in every 50 babies born suffers from a congenital heart defect – and again, therapies are few and far between, as we know little why they arise. What is missing in understanding both heart disease and cardiac malformations is a model comprising the major regions of the human heart. Now, the Mendjan team at IMBA presents the first physiological organoid model that includes all the principal developing heart structures and allows researchers to study cardiac disease and development.

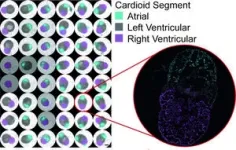

In 2021, the Mendjan lab presented the first chamber-like organoid heart model formed from human induced pluripotent stem cells. These self-organizing heart organoids, or Cardioids, recapitulated the development of the heart’s left ventricular chamber in the very early days of embryogenesis. “These Cardioids were a proof-of-principle and an important step forward,” says Mendjan. “While most adult diseases affect the left ventricle, which pumps oxygenated blood through the body, congenital defects affect mostly other heart regions essential to establish and maintain circulation.”

In the new study, the team at IMBA expanded on their previous work. The researchers first derived organoid models of each developing heart structure individually. “Then we asked: If we let all these organoids co-develop together, do we get a heart model that co-ordinately beats like the early human heart?”, Mendjan explains.

Unraveling human heart development

After growing left and right ventricular and the atrial organoids together, the researchers were in for a surprise: “Indeed, an electrical signal spread from the atrium to the left and then the right ventricular chambers – just like in early fetal heart development in animals,” Mendjan recalls. “We now observed this fundamental process in a human heart model for the first time, with all its chambers.”

While the previous Cardioid model allowed the researchers to study the chamber’s shape and tissue organization, the newly developed multi-chamber Cardioids enabled them to go beyond, studying how regional gene expression differences lead to specific chamber contraction patterns and intricate communication between them.

The researchers have already gained insight into early heart development, particularly how the human heart starts beating – which has not been understood so far. “We saw that as the organoid chambers developed, they performed an intricate dance of lead and follow. At first, the left ventricular chamber leads the budding right ventricular and atrium chambers at its rhythm. Then, as the atrium develops- two days later- the ventricles follow the atrial lead. This mirrors what is seen in animals before the final leaders, the pacemakers, control the heart rhythm”, explains Alison Deyett, a PhD student in the Mendjan group and one of the study’s first authors.

Screening platform for congenital heart disease & therapy

In addition to studying human development, multi-chamber Cardioids enable researchers to investigate chamber-specific defects. In a proof-of-principle, the Mendjan team set up a screening platform for defects, in which they study how known teratogens and mutations affect hundreds of heart organoids simultaneously.

Thalidomide, a well-known teratogen in humans, and retinoid derivatives – used in treatments against leukaemia, psoriasis, and acne – are known to cause severe heart defects in the fetus. Both teratogens induced similar, severe compartment-specific defects in the heart organoids. In a similar way, mutations in three cardiac transcription factor genes led to chamber-specific defects seen in human development. “Our tests show that multi-chamber Cardioids recapitulate embryonic heart development and can uncover disruptive effects on the whole heart with high specificity. We do this using a holistic approach, looking at multiple readouts simultaneously “, Mendjan sums up.

In the future, multi-chamber heart organoids can be used for toxicology studies and to develop new drugs with heart chamber-specific effects. “For example, atrial arrhythmias are widespread, but we currently don’t have good drugs to treat it. One reason is that no models existed comprising all regions of the developing heart working in a coordinated manner – so far”, Mendjan adds. And although heart defects are common, including as the leading cause of miscarriages, the individual origin often remains unknown.

Heart organoids developed from patient-derived stem cells could, in the future, give insight into the developmental defect and how it may be treated and prevented. The Mendjan group is particularly interested in using multi-chamber heart organoids to understand heart development further: “We now have a basis to investigate the heart’s further growth and regenerative potential.”

IMBA has granted an exclusive license of the multi-chamber cardiac organoid technology to HeartBeat.bio AG (www.heartbeat.bio), a spin-off company of IMBA, which Sasha Mendjan co-founded. Several researchers at HeartBeat.bio contributed scientifically to the new publication. The company has already translated IMBA’s left-ventricular Cardioid technology into a fully automated and integrated human 3D drug discovery platform tackling different forms of heart failure. The licensing of the multi-chamber model enables HeartBeat.bio to expand its portfolio of disease models further, providing more opportunities for building a cardiac drug discovery pipeline.

END

First multi-chamber heart organoids unravel human heart development and disease

2023-11-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Race and ethnicity and emergency department discharge against medical advice

2023-11-28

About The Study: The findings of this study of 33.1 million visits to 989 U.S. hospitals suggest that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely to receive care in hospitals with higher overall discharge against medical advice (DAMA) rates, suggesting interventions should address medical segregation. Structural racism may contribute to emergency department DAMA disparities via unequal allocation of health care resources in hospitals that disproportionately treat racial and ethnic minoritized groups. Monitoring variation in DAMA by race and ethnicity and hospital suggests ...

Strategies to increase cervical cancer screening with mailed HPV self-sampling kits

2023-11-28

About The Study: Direct-mail human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling increased cervical cancer screening by more than 14% in individuals who were due or overdue for cervical cancer screening in this randomized clinical trial of 31,000 individuals. The opt-in approach minimally increased screening. To increase screening adherence, systems implementing HPV self-sampling should prioritize direct-mail outreach for individuals who are due or overdue for screening. For individuals with unknown screening history, ...

Scientists track rapid retreat of Antarctic glacier

2023-11-28

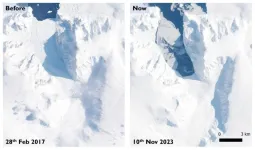

Scientists are warning that apparently stable glaciers in the Antarctic can “switch very rapidly” and lose large quantities of ice as a result of warmer oceans.

Their finding comes after a research team led by Benjamin Wallis, a glaciologist at the University of Leeds, used satellites to track the Cadman Glacier, which drains into Beascochea Bay, on the west Antarctic peninsula.

Between November 2018 and May 2021, the glacier retreated eight kilometres as the ice shelf at the end ...

A new way to see the activity inside a living cell

2023-11-28

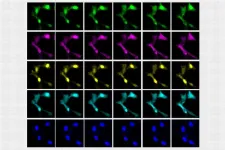

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Living cells are bombarded with many kinds of incoming molecular signal that influence their behavior. Being able to measure those signals and how cells respond to them through downstream molecular signaling networks could help scientists learn much more about how cells work, including what happens as they age or become diseased.

Right now, this kind of comprehensive study is not possible because current techniques for imaging cells are limited to just a handful of different molecule types within a cell at one time. However, MIT researchers have developed ...

Prioritizing circulation before the airway in trauma may improve outcomes for patients with massive bleeding

2023-11-28

Key takeaways

· A paradigm shift in trauma care: The circulation-airway-breathing (CAB) sequence has gained acceptance over the past decade over the airway-breathing-circulation (ABC) model for patients with severe bleeding injuries.

· Better outcomes: A literature review found significantly lower mortality rates with CAB vs. ABC for patients with severe bleeding injuries.

CHICAGO (November 28, 2023): For trauma patients suffering from massive blood loss, a care approach that emphasizes halting bleeding and restoring ...

Australian patients coping with mesothelioma experienced higher levels of toxicity on CheckMate743 regimen than reported in clinical trials

2023-11-28

Based on results from the CheckMate743 trial, the dual regimen of ipilimumab and nivolumab is the standard of care for the treatment of unresectable pleural mesothelioma. But research published today in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology (JTO) showed that a group of Australian patients treated with that immunotherapy combination experienced higher levels of toxicity than were reported in the clinical trial results. The study is available here: https://www.jto.org/article/S1556-0864(23)02370-5/fulltext.

JTO is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Australia ...

More to learn about reducing the churn: Examining the pandemic’s continuous enrollment Medicare policy

2023-11-28

Boston, MA – A new study led by researchers at the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute has found that a federal policy implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic requiring continuous enrollment in Medicaid led to a significant reduction in the rates of becoming uninsured for adult Medicaid enrollees.

The study, “Continuous Medicaid coverage during the COVID-19 public health emergency reduced churning, but did not eliminate it,” was published in the October 21 edition of Health Affairs Scholar.

Many people who have Medicaid coverage frequently gain and lose it, sometimes over short periods of time. This phenomenon ...

No significant link between industry 4.0 and energy consumption or energy intensity

2023-11-28

To what extent does the digitalisation of industrial and manufacturing processes (Industry 4.0) improve energy efficiency and thus reduce energy intensity? A team from the Research Institute for Sustainability (RIFS) analysed developments across ten industrial manufacturing sectors in China between 2006 and 2019. Their findings show that contrary to the claims of many policymakers and industry associations, digitalisation may not automatically lead to anticipated energy savings in manufacturing and industry in China.

China accounts for 30% of global manufacturing value added and the largest share of global manufacturing ...

Weill Cornell Medicine to open medical research center at 1334 York Avenue

2023-11-28

Weill Cornell Medicine is dramatically expanding its campus and research footprint in New York City by securing five floors of 1334 York Ave., the current home of Sotheby's auction house, the institution announced today.

Located one block from Weill Cornell Medicine’s main campus on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, the site will add approximately 200,000 square feet of dedicated research space—an average of 40,000 square feet per floor—making it the institution’s largest expansion since the Belfer Research Building opened in 2014. Laboratories in the new medical ...

What if Alexa or Siri sounded more like you? Study says you’ll like it better

2023-11-28

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — One voice does not fit all when it comes to virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa, according to a team led by Penn State researchers that examined how customization and perceived similarity between user and voice assistant (VA) personalities affect user experience. They found a strong preference for extroverted VAs — those that speak louder, faster and in a lower pitch. They also found that increasing personality similarity by automatically matching user and VA voice profiles encouraged users to resist persuasive information, such as misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines. In the study, 38% of unvaccinated individuals changed their minds about vaccination ...