(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. – The discovery of a planet that is far too massive for its sun is calling into question what was previously understood about the formation of planets and their solar systems, according to Penn State researchers.

In a paper published online today (Nov. 30) in the journal Science, researchers report the discovery of a planet more than 13 times as massive as Earth orbiting the “ultracool” star LHS 3154, which itself is nine times less massive than the sun. The mass ratio of the newly found planet with its host star is more than 100 times higher than that of Earth and the sun.

The finding reveals the most massive known planet in a close orbit around an ultracool dwarf star, the least massive and coldest stars in the universe. The discovery goes against what current theories would predict for planet formation around small stars and marks the first time a planet with such high mass has been spotted orbiting such a low-mass star.

“This discovery really drives home the point of just how little we know about the universe,” said Suvrath Mahadevan, the Verne M. Willaman Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State and co-author on the paper. “We wouldn’t expect a planet this heavy around such a low-mass star to exist.”

He explained that stars are formed from large clouds of gas and dust. After the star is formed, the gas and dust remain as disks of material orbiting the newborn star, which can eventually develop into planets.

“The planet-forming disk around the low-mass star LHS 3154 is not expected to have enough solid mass to make this planet,” Mahadevan said. “But it’s out there, so now we need to reexamine our understanding of how planets and stars form.”

The researchers spotted the oversized planet, named LHS 3154b, using an astronomical spectrograph built at Penn State by a team of scientists led by Mahadevan. The instrument, called the Habitable Zone Planet Finder or HPF, was designed to detect planets orbiting the coolest stars outside our solar system with the potential for having liquid water — a key ingredient for life — on their surfaces.

While such planets are very difficult to detect around stars like our sun, the low temperature of ultracool stars means that planets capable of having liquid water on their surface are much closer to their star relative to Earth and the sun. This shorter distance between these planets and their stars, combined with the low mass of the ultracool stars, results in a detectable signal announcing the presence of the planet, Mahadevan explained.

“Think about it like the star is a campfire. The more the fire cools down, the closer you’ll need to get to that fire to stay warm,” Mahadevan said. “The same is true for planets. If the star is colder, then a planet will need to be closer to that star if it is going to be warm enough to contain liquid water. If a planet has a close enough orbit to its ultracool star, we can detect it by seeing a very subtle change in the color of the star’s spectra or light as it is tugged on by an orbiting planet.”

Located at the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at the McDonald Observatory in Texas, the HPF provides some of the highest precision measurements to date of such infrared signals from nearby stars.

“Making the discovery with HPF was extra special, as it is a new instrument that we designed, developed and built from the ground-up for the purpose of looking at the uncharted planet population around the lowest mass stars,” said Guðmundur Stefánsson, NASA Sagan Fellow in Astrophysics at Princeton University and lead author on the paper, who helped develop HPF and worked on the study as a graduate student at Penn State. “Now we are reaping the rewards, learning new and unexpected aspects of this exciting population of planets orbiting some of the most nearby stars.”

The instrument has already yielded critical information in the discovery and confirmation of new planets, Stefánsson explained, but the discovery of the planet LHS 3154b exceeded all expectations.

“Based on current survey work with the HPF and other instruments, an object like the one we discovered is likely extremely rare, so detecting it has been really exciting,” said Megan Delamer, astronomy graduate student at Penn State and co-author on the paper. “Our current theories of planet formation have trouble accounting for what we’re seeing."

In the case of the massive planet discovered orbiting the star LHS 3154, the heavy planetary core inferred by the team’s measurements would require a larger amount of solid material in the planet-forming disk than current models would predict, Delamer explained. The finding also raises questions about prior understandings of the formation of stars, as the dust-mass and dust-to-gas ratio of the disk surrounding stars like LHS 3154 — when they were young and newly formed — would need to be 10 times higher than what was observed in order to form a planet as massive as the one the team discovered.

“What we have discovered provides an extreme test case for all existing planet formation theories,” Mahadevan said. “This is exactly what we built HPF to do, to discover how the most common stars in our galaxy form planets — and to find those planets.”

Other Penn State authors on the paper are Eric Ford, Brianna Zawadzki, Fred Hearty, Andrea Lin, Lawrence Ramsey and Jason Wright. Other authors on the paper are Joshua Winn of Princeton University, Yamila Miguel of the University of Leiden, Paul Robertson of the University of California, Irvine, and Rae Holcomb of the University of California, Shubham Kanodia of the Carnegie Institution for Science, Caleb Cañas of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Joe Ninan of India’s Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Ryan Terrien of Carleton College, Brendan Bowler, William Cochran, Michael Endl and Gary Hill of The University of Texas at Austin, Chad Bender of The University of Arizona, Scott Diddams, Connor Fredrick and Andrew Metcalf of the University of Colorado, Samuel Halverson of California Institute of Technology’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Andrew Monson of the University of Arizona, Arpita Roy of Johns Hopkins University, Christian Schwab of Australia ‘s Macquarie University, and Gregory Zeimann of the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at UT Austin.

The work was funded by the Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds at Penn State, the Pennsylvania Space Grant Consortium, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Science Foundation and the Heising-Simons Foundation.

END

Discovery of planet too big for its sun throws off solar system formation models

2023-11-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Early rhythm control, lifestyle modification and more tailored stroke risk assessment are top goals in managing atrial fibrillation

2023-11-30

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA), along with several other leading medical associations, have issued a new guideline for preventing and optimally managing atrial fibrillation (AFib). The guideline was jointly published today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation.

Atrial fibrillation, or AFib, is the most common type of heart rhythm disorder (arrhythmia), affecting over 6 million Americans, and the number is expected to double by 2030. AFib causes a variety of symptoms, including fast ...

Carbon dioxide becomes more potent as climate changes, study finds

2023-11-30

Embargoed: Not for Release Until 2:00 pm U.S. Eastern Time Thursday, 30 November 2023.

A team of scientists found that carbon dioxide becomes a more potent greenhouse gas as more is released into the atmosphere.

The new study, led by scientists at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, Science, was published in Science and comes as world leaders meet in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, this week for the United Nations Climate Change Conference COP28.

“Our finding means that ...

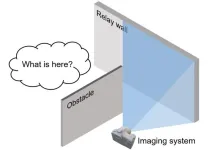

Researchers extend non-line-of-sight imaging towards longer wavelengths

2023-11-30

WASHINGTON — Emerging technologies for non-line-of-sight imaging can detect objects even if they are around a corner or behind a wall. In new work, researchers use a new type of detector to extend this method from visible light into near and mid-infrared wavelengths, an advance that could be especially useful for unmanned vehicles, robotic vision, endoscopy and other applications.

“Infrared non-line-of-sight imaging can improve the safety and efficiency of unmanned vehicles by helping them detect and navigate around obstacles that are not directly visible,” said Xiaolong Hu from Tianjin University in China. His team collaborated with a group ...

EU/EEA: HIV diagnoses rise for the first time in a decade

2023-11-30

Across the 30 countries of the European Union and European Economic Area (EU/EEA), 22,995 new HIV diagnoses were reported in 2022. Almost every second new HIV diagnosis (49%, n=11,103) was among migrants, i.e. among people who were not born in in the country they were diagnosed in. born abroad from the country of their diagnosis.

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, more than 4 million Ukrainians took refuge in countries of the European Union and European Economic Area (EU/EEA). In a rapid communication published in Eurosurveillance prior to World AIDS Day 2023 on 1 December, Reyes-Urueña et al. look at most recent surveillance data ...

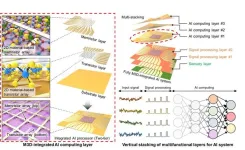

2D material reshapes 3D electronics for AI hardware

2023-11-30

Multifunctional computer chips have evolved to do more with integrated sensors, processors, memory and other specialized components. However, as chips have expanded, the time required to move information between functional components has also grown.

“Think of it like building a house,” said Sang-Hoon Bae, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis. “You build out laterally and up vertically to get more ...

George Demetri, MD, of Dana-Farber earns Lifetime Achievement Award in Medicine from Stanford University School of Medicine

2023-11-30

Boston – George Demetri, MD, director of the Sarcoma Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, is being awarded the prestigious J.E. Wallace Sterling Lifetime Achievement Award in Medicine from the Stanford Medicine Alumni Association (SMAA). Demetri, an alumnus of the Stanford University School of Medicine, Class of 1983, will be honored at a dinner held on the Stanford University School of Medicine campus on December 4, 2023.

“Dr. Demetri is a leader in developing targeted therapeutics for cancer and has been pivotal in advancing oncology treatments ...

Snake skulls show how species adapt to prey

2023-11-30

By studying the skull shapes of dipsadine snakes, researchers at The University of Texas at Arlington have found how these species of snakes in Central and South America have evolved and adapted to meet the demands of their habitats and food sources.

The research, conducted in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Michigan, was published in the peer-reviewed journal BMC Ecology and Evolution.

“We now have evidence that this group of snakes is one of the most spectacular and largest vertebrate adaptive radiations currently known to science,” said Gregory Pandelis, collections manager at UTA’s Amphibian and Reptile Diversity ...

IU researchers develop new brain network modeling tools to advance Alzheimer's disease research

2023-11-30

INDIANAPOLIS—Indiana University researchers are collaborating on a novel approach to use neuroimaging and network modeling tools—previously developed to analyze brains of patients in the clinic—to investigate Alzheimer’s disease progression in preclinical animal models.

The research team, led by Evgeny Chumin, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at IU Bloomington, and Paul Territo, PhD, professor of medicine at the IU School of Medicine, published their findings in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of ...

Sea fireflies synchronize their sparkle to seek soulmates

2023-11-30

ITHACA, N.Y. -- In sea fireflies’ underwater ballet, the males sway together in perfect, illuminated synchronization, basking in the glow of their secreted iridescent mucus.

“It’s extreme,” said Nicholai M. Hensley, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior in the College of Arts and Sciences. “It’s an illustration of convergent evolution and a striking example of synchronized bioluminescent mating displays. The males are putting it all out on the dance floor. It’s a big bright display.”

Hensley is the lead author of new research unwrapping the vivid mating ...

Structural racism persists in radiotherapy

2023-11-30

Philadelphia, November 30, 2023 – Everyone should get quality care, no matter the color of their skin. However, implicit bias, micro-aggressions, and a lack of cultural understanding persist, leading to oppression and unequal treatment in healthcare. An insightful article in the new themed issue of the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences on specialized populations, published by Elsevier, highlights this serious problem, specifically addressing the assessment and treatment of radiation-induced skin reactions (RISR) in patients across the world undergoing external beam radiotherapy.

The article provides a stark example ...