(Press-News.org)

LAWRENCE — Research appearing in ACS Nano, a premier journal on nanoscience and nanotechnology, reveals the ballistic movement of electrons in graphene in real time.

The observations, made at the University of Kansas’ Ultrafast Laser Lab, could lead to breakthroughs in governing electrons in semiconductors, fundamental components in most information and energy technology.

“Generally, electron movement is interrupted by collisions with other particles in solids,” said lead author Ryan Scott, a doctoral student in KU’s Department of Physics & Astronomy. “This is similar to someone running in a ballroom full of dancers. These collisions are rather frequent — about 10 to 100 billion times per second. They slow down the electrons, cause energy loss and generate unwanted heat. Without collisions, an electron would move uninterrupted within a solid, similar to cars on a freeway or ballistic missiles through air. We refer to this as ‘ballistic transport.’”

Scott performed the lab experiments under the mentorship of Hui Zhao, professor of physics & astronomy at KU. They were joined in the work by former KU doctoral student Pavel Valencia-Acuna, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Northwest Pacific National Laboratory.

Zhao said electronic devices utilizing ballistic transport could potentially be faster, more powerful and more energy efficient.

“Current electronic devices, such as computers and phones, utilize silicon-based field-effect transistors,” Zhao said. “In such devices, electrons can only drift with a speed on the order of centimeters per second due to the frequent collisions they encounter. The ballistic transport of electrons in graphene can be utilized in devices with fast speed and low energy consumption.”

The KU researchers observed the ballistic movement in graphene, a promising material for next-generation electronic devices. First discovered in 2004 and awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010, graphene is made of a single layer of carbon atoms forming a hexagonal lattice structure — somewhat like a soccer net.

“Electrons in graphene move as if their ‘effective’ mass is zero, making them more likely to avoid collisions and move ballistically,” Scott said. “Previous electrical experiments, by studying electrical currents produced by voltages under various conditions, have revealed signs of ballistic transport. However, these techniques aren’t fast enough to trace the electrons as they move.”

According to the researchers, electrons in graphene (or any other semiconductor) are like students sitting in a full classroom, where students can’t freely move around because the desks are full. The laser light can free electrons to momentarily vacate a desk, or ‘hole’ as physicists call them.

“Light can provide energy to an electron to liberate it so that it can move freely,” Zhao said. “This is similar to allowing a student to stand up and walk away from their seat. However, unlike a charge-neutral student, an electron is negatively charged. Once the electron has left its ‘seat,’ the seat becomes positively charged and quickly drags the electron back, resulting in no more mobile electrons — like the student sitting back down.”

Because of this effect, the super-light electrons in graphene can only stay mobile for about one-trillionth of a second before falling back to its seat. This short time presents a severe challenge to observing the movement of the electrons. To address this problem, the KU researchers designed and fabricated a four-layer artificial structure with two graphene layers separated by two other single-layer materials, molybdenum disulphide and molybdenum diselenide.

“With this strategy, we were able to guide the electrons to one graphene layer while keeping their ‘seats’ in the other graphene layer,” Scott said. “Separating them with two layers of molecules, with a total thickness of just 1.5 nanometers, forces the electrons to stay mobile for about 50-trillionths of a second, long enough for the researchers, equipped with lasers as fast as 0.1 trillionth of a second, to study how they move.”

The researchers use a tightly focused laser spot to liberate some electrons in their sample. They trace these electrons by mapping out the “reflectance” of the sample, or the percentage of light they reflect.

“We see most objects because they reflect light to our eyes,” Scott said. “Brighter objects have larger reflectance. On the other hand, dark objects absorb light, which is why dark clothes become hot in the summer. When a mobile electron moves to a certain location of the sample, it makes that location slightly brighter by changing how electrons in that location interact with light. The effect is very small — even with everything optimized, one electron only changes the reflectance by 0.1 part per million.”

To detect such a small change, the researchers liberated 20,000 electrons at once, using a probe laser to reflect off the sample and measure this reflectance, repeating the process 80 million times for each data point. They found the electrons on average move ballistically for about 20-trillionths of a second with a speed of 22 kilometers per second before running into something that terminates their ballistic motion.

The research was funded by a grant from the Department of Energy under the program of Physical Behavior of Materials.

Zhao said currently his lab is working to refine their material design to guide electrons more efficiently to the desired graphene layer, and trying to find ways to make them move longer distances ballistically.

END

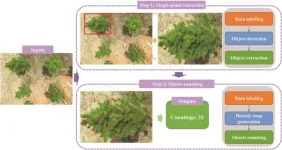

In southern China, the genetically improved slash pine (Pinus elliottii) plays a crucial role in timber and resin production, with new shoot density being a key growth trait. Current manual counting methods are inefficient and inaccurate. Emerging technologies such as UAV-based RGB imaging and deep learning (DL) offer promising solutions. However, DL methods face challenges in global feature capture, necessitating additional mechanisms. Innovations like the Vision Transformer and its derivatives (e.g., TransCrowd, CCTrans) show potential in plant trait counting, offering simplified and more effective approaches for large-scale and accurate ...

BALTIMORE, December 14, 2023– In a landmark study led by the University of Maryland School of Medicine, researchers discovered for the first time that a certain kind of protein similar to hemoglobin, called cytoglobin, plays an important role in the development of the heart. Specifically, it affects the correct left-right pattern of the heart and other asymmetric organs. The findings, published today in the journal Nature Communications, could eventually lead to the development of new therapeutic interventions to alter the processes that lead ...

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL FRIDAY DECEMBER 15 AT 11 A.M. EST.

U.S. hospitals charge facility fees for colonoscopy procedures covered by private health insurance that are on average approximately 55 percent higher than facility fees billed by smaller clinics known as ambulatory surgical centers, according to a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The findings appear in a peer-reviewed research letter to be published online December 15 in JAMA Health Forum.

Colonoscopies ...

About The Study: The results of this study of data on 57,000 adults who received living donor kidney transplants indicate that additional work is necessary to identify transplant program and center-level strategies to improve racial equity in access to living donor kidney transplant.

Authors: Lisa M. McElroy, M.D., M.S., of the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.47826)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, ...

About The Study: In this study of 18,000 academic physicians, approximately one-third reported moderate or greater intention to leave within two years. Burnout, lack of professional fulfillment, and other well-being factors were associated with intention to leave, suggesting the need for a comprehensive approach to reduce physician turnover.

Authors: Mickey T. Trockel, M.D., Ph.D., of the Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit ...

About The Study: Fewer calories were purchased in restaurants with calorie labels compared with those with no labels, suggesting that consumers are sensitive to calorie information on menu boards, according to the results of this study of 2,329 Mexican-inspired fast food restaurants in six U.S. locations. Associations differed by location.

Authors: Brian Elbel, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the New York University School of Medicine in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.46851)

Editor’s ...

About The Study: The findings of this diagnostic study of 1,890 eyes of 958 participants support the potential of artificial intelligence as an objective tool in screening for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and possibly for symptom severity using retinal photographs. Retinal photograph use may speed the ASD screening process, which may help improve accessibility to specialized child psychiatry assessments currently strained by limited resources.

Authors: Yu Rang Park, Ph.D., and Keun-Ah Cheon, M.D., Ph.D., ...

Positive tipping points must be triggered if we are to avoid the severe consequences of damaging Earth system tipping points, researchers say.

With global warming on course to breach 1.5oC, at least five Earth system tipping points are likely to be triggered – and more could follow.

Once triggered, Earth system tipping points would have profound local and global impacts, including sea-level rise from major ice sheet melting, mass species extinction from dieback of the Amazon rainforest and disruption to weather patterns from a collapse of large-scale ocean circulation currents.

The new commentary – published in One Earth by researchers from the Global Systems Institute at ...

A paper published today in JAMA Network Open addresses bias in healthcare algorithms and provides the healthcare community with guiding principles to avoid repeating errors that have tainted the use of algorithms in other sectors.

This work, conducted by a technical expert panel co-chaired by Marshall Chin, MD, MPH, the Richard Parrillo Family Distinguished Service Professor of Healthcare Ethics at the University of Chicago, supports the Biden Administration Executive Order 14091, Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through The Federal Government, issued on February 16, 2023. President Biden calls for Federal ...

In a rapid communication published in the journal Genes & Diseases, researchers from Chongqing Medical University and Yongchuan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Chongqing have unveiled crucial insights into the factors that might influence Intervertebral Disc Degeneration (IDD). IDD is a predominant cause of lower back pain, impacting millions worldwide. The focus of this research revolved around nucleus pulposus cells (NPCs), pivotal in IDD, and how oxygen levels and the HIF1A gene could influence them. ...