(Press-News.org) Wars, drought, displacement, and instability are causing a dramatic increase in the number of pregnant and breastfeeding women around the world who suffer from malnutrition. Without access to sufficient nutrients in the womb, babies born to these women are more likely to die due to complications like pre-term birth, low birth weight, and susceptibility to diseases like malaria. To try to reduce the risk of malarial infection, the WHO recommends that pregnant women in low-income countries be treated with a combination of the antimalarial drugs sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine (SP). Curiously, a recent study found that this treatment also seemed to increase the birth weight of treated mothers’ babies, regardless of whether they contracted malaria.

Intrigued by this finding, which was brought to their attention by members of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a team of scientists at the Wyss Institute decided to investigate the phenomenon using its human Intestine Chip. With support from the Foundation, the team found that chips exposed to malnutrition conditions displayed classic features of intestinal dysfunction, and that these issues were almost fully resolved by the addition of SP. The research is published in eBioMedicine.

"Our primary goal in conducting this study was to find ways to promote maternal health and improve birth outcomes,” said first author Seongmin Kim, Ph.D., a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wyss Institute. “I’m driven to pursue meaningful research that benefits women, including my beloved mother, wife, and daughter who is still in utero. I hope that this work galvanizes future clinical studies to significantly improve human health worldwide."

Modeling malnutrition

When Kim read the study suggesting that SP improved infant birth weight by counteracting malnutrition, he searched for more clinical data about the drug’s effects on the human intestine. But he found nothing. “Very few clinical trials include pregnant women for ethical reasons, and there was no existing human in vitro model to use for studying this drug. But I knew we could use our Intestine Chip to create the missing model and generate some useful data,” says Kim.

The Wyss Institute’s Organ Chip technology faithfully replicates many functions of human organs inside a device about the size and shape of a USB memory stick. The chip has two parallel channels separated by a porous membrane. One channel is coated with human blood vessel cells to mimic the vascular system, while the other channel is coated with living human organ cells. In the case of the Intestine Chip, rhythmic stretching is applied to the device to replicate the conditions that human intestines experience due to muscular waves of peristalsis during digestion.

In previous work, the team built a version of the Intestine Chip that replicated pediatric environmental enteric dysfunction (EED), a devastating childhood disease caused by long-term malnutrition. Kim sought to extend the team’s demonstrated approach in modeling pediatric EED to newly model the intestine of mothers, investigating how malnutrition affected them. He and his coauthors obtained tissue biopsy samples from healthy young women and cultured the cells inside the Intestine Chip, creating miniature versions of their small intestines in the lab.

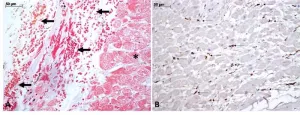

To mimic healthy intestine, they flowed a nutrient-rich medium through the blood vessel channel to mimic the delivery of nutrients through the bloodstream, and confirmed that the cells in the intestinal channel were healthy and functional, as the team had previously demonstrated in the pediatric EED chips. They spontaneously developed villi-like structures that replicate the tiny projections found on human intestinal cells, produced mucus, and maintained an intact intestinal barrier between the cells.

Then, the team switched out the medium for a nutrient-deficient version that lacked niacinamide (a vitamin) and tryptophan (an essential amino acid). The result was similar to that observed in the pediatric EED chips: the villi were noticeably shorter, there was less mucus production, and the connections between the cells had begun to break down, creating a “leaky gut.” These changes were detectable on the genetic level as well, with lower activity of genes associated with villi formation and mucus production. The researchers had created a functional Organ Chip model of the intestinal effects of malnutrition in adults for the first time.

SP to the rescue

The team could now use this new model to investigate how SP might affect these negative hallmarks of malnutrition. First, they added the drug combination to the Intestine Chip along with the nutrient-rich medium for three days and observed no significant changes. Then, they added SP to chips that had only received the nutrient-deficient medium and looked malnourished. The results were clear: the villi grew taller, mucus production went up, and the intestinal barrier function improved.

But just because the SP-treated Intestine Chips looked more normal didn’t necessarily mean that they were getting better nutrition. Thus, the team went further to look specifically at how SP affected nutrient absorption from the chips. They analyzed the RNA molecules that were present in healthy, malnourished, and SP-treated malnourished chips. They found that genetic pathways that are critical for digestion; the metabolism of triglycerides, fatty acids, and vitamins; and intestinal absorption of vital nutrients were suppressed in their nutrient-deficient chips.

When those chips were treated with SP, the same analysis showed a reactivation of many metabolic and absorption pathways. Another experiment using a fluorescently labeled fatty acid found that malnourished chips absorbed 3.5 times less of the fatty acid compared to healthy chips, but this effect was reversed when the malnourished chips were treated with SP.

“Our research shows that SP treatment does indeed have multiple direct effects on the human adult female intestine, which could help explain why pregnant mothers who are prophylactically treated with SP as an antimalarial therapy had babies with healthier birth weights,” said co-author Girija Goyal, Ph.D., a Senior Scientist at the Wyss Institute. “The increased surface area of the villi in Intestine Chips treated with SP increases the surface area available to absorb nutrients from the blood, the thicker mucus layer protects the intestinal cells from pathogens, and the increased expression of genes that are crucial for nutrient and fatty acid absorption helps maintain health.”

Another known effect of malnutrition is increased inflammation in the intestine, which can cause a host of problems. Consistent with these previous results, the team detected higher levels of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines in malnourished Intestine Chips compared to healthy chips. When the chips were given SP, their cytokine levels went down, and the level of a specific protein called LCN2 increased. LCN2 is known to maintain a healthy intestinal microbiome and protect against inflammation.

Finally, because immune cells can also mediate inflammation, the researchers introduced human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) into the blood vessel channel of the Intestine Chip. They found that in malnourished chips, these immune cells stuck to the surface of the intestinal channel, indicating a potential immune response. This behavior was also significantly reduced by SP treatment.

Hope for mothers and babies in the future

While they are excited about their results, the researchers caution that their human Intestine Chip model does not replicate pregnancy, so it does not provide direct evidence of how the treatment of maternal malnutrition with SP impacts their babies’ health. Pregnancy introduces many new factors into a mother’s biology including hormonal changes and immune responses, so further in-depth clinical trials of SP are required to establish its safety and efficacy for pregnant women.

“This work makes a clear argument that SP should be further explored as a potential treatment for the serious global health problem of malnutrition, which will only get worse as climate change and related conflicts affect the poorest and most vulnerable populations around the world,” said senior author and Wyss Founding Director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D. “We also hope our Intestine Chip can help answer other important questions related to intestinal health and disease on the global scale.” Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and the Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Bioinspired Engineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Additional co-authors include Abidemi Junaid from the Wyss Institute; former Wyss Institute members Arash Naziripour, Pranav Prabhala, and Viktor Horváth; and David Breault from Harvard Medical School, BCH, and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

This research was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, and the National Institutes of Health through grant P30 DK034854. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

END

A malaria drug treatment could save babies’ lives

Human organ chip research shows that a common antimalarial combination could reverse the negative effects of malnutrition in the female digestive tract that lead to low birth weight infants

2023-12-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Engineered human heart tissue shows Stanford Medicine researchers the mechanics of tachycardia

2023-12-19

Heart rates are easier to monitor today than ever before. Thanks to smartwatches that can sense a pulse, all it takes is a quick flip of the wrist to check your heart. But monitoring the cells responsible for heart rate is much more challenging — and it’s encouraged researchers to invent new ways to analyze them.

Joseph Wu, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute and professor of medicine and of radiology, has devised a new stem cell-derived model of heart tissue ...

Molecular jackhammers’ ‘good vibrations’ eradicate cancer cells

2023-12-19

The Beach Boys’ iconic hit single “Good Vibrations” takes on a whole new layer of meaning thanks to a recent discovery by Rice University scientists and collaborators, who have uncovered a way to destroy cancer cells by using the ability of some molecules to vibrate strongly when stimulated by light.

The researchers found that the atoms of a small dye molecule used for medical imaging can vibrate in unison ⎯ forming what is known as a plasmon ⎯ when stimulated by near-infrared light, causing the cell membrane of cancerous cells to rupture. ...

Nearly 30% of caregivers for severe stroke survivors experience psychological distress

2023-12-19

Stroke is an abrupt, devastating disease that instantly changes a person’s life and has the potentially to cause lasting disability or death. However, the condition also has profound effects on the patient’s loved ones — who are often called to make difficult decisions quickly.

A new study led by Michigan Medicine finds that nearly 30% of caregivers of severe stroke patients experience high levels of anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress during the first year after the patient leaves the hospital.

The results are published in Neurology.

“As physicians, we usually concentrate on our ...

MSU research suggests pandas are active posters on ‘social media’

2023-12-19

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

Images

Pandas, long portrayed as solitary creatures, do hang with family and friends — and they’re big users of “social media.” Scent-marking trees serve as a panda version of Facebook.

An article in the international journal Ursus paints a new lifestyle picture of the beloved bears in China’s Wolong National Nature Reserve, a life that’s shielded from human eyes because they’re shy, rare and live in densely forested, remote areas. No one really knows how pandas hang, but a new study indicates pandas are around others more than previously thought. ...

UTHSC, Vanderbilt University receive $2.4 million grant to promote diversity in speech-language pathologists for high-need children

2023-12-19

The Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and the Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences at Vanderbilt University have secured a $2,399,454 grant to fund a five-year project to address the need for diversity in highly trained professionals in speech-language pathology.

The project, known as Project PAL (Preparing Academic Leaders in Speech-Language Pathology to Teach, Conduct Research, and Engage in Professional Service to Improve Outcomes for Children with High Need Communication Disorders), ...

American University receives $5.7 million from NSF to bridge research and policy, address real-world challenges

2023-12-19

American University won a $5.7 million cooperative research agreement from the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Accelerating Research Translation program. The award will help AU foster greater use of evidence in the public and private sectors by producing new knowledge on best practices in research translation, training scholars in the effective conduct of research translation, and supporting the dissemination of research findings that have the potential to benefit society.

The ART program ...

UTRF Innovation Awards celebrate UTHSC researchers

2023-12-19

The University of Tennessee Research Foundation (UTRF) celebrated the researchers whose achievements are making life better locally, nationally, and globally at its annual Innovation Awards ceremony, held December 14 at the Mooney Library at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC) in Memphis.

The Innovation Awards recognize researchers from all over the UT System who partner with UTRF to bring their innovations to market. “Turning research into practical, sustainable solutions calls for resilience, adaptability, and market savvy. Let's collectively celebrate the foundational research successes that made ...

Groundbreaking hip-focused physical therapy reduces low back pain

2023-12-19

When the University of Delaware’s Gregory Hicks started his research career two decades ago, he was one of only a few people in the United States studying chronic low back pain in people over 60 years old.

Fast-forward to today, the research on back pain has ramped up, yet studies of older adults with the problem are still sparse.

“Unfortunately, the societal attitude is that older people don’t warrant the same level of care that younger people do when it comes to musculoskeletal problems,” said Hicks, Distinguished Professor of Health Sciences at UD. “But I don’t believe that for a ...

Researchers report detailed analysis of heart injury caused by yellow fever virus

2023-12-19

To fill gaps in knowledge of yellow fever (YF), a group of researchers in Brazil affiliated with the Department of Pathology at the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP), Hospital das Clínicas (HC, the hospital complex run by FM-USP), the Heart Institute (InCor, linked to HC) and Emílio Ribas Institute of Infectious Diseases (IIER) decided to study the pathogenesis of YF-associated heart injury.

The team was led by Fernando Rabioglio Giugni, a cardiologist, and Amaro Nunes Duarte-Neto, an infectious disease specialist and pathologist; both work at FM-USP.

“There’s still no specific treatment for yellow fever. Patients receive ...

David Kaplan named fellow of the National Academy of Inventors

2023-12-19

David Kaplan, the Stern Family Endowed Professor of Engineering, has been named a fellow of the National Academy of Inventors (NAI). Election as an academy fellow is the highest professional distinction awarded solely to inventors. The NAI was founded to recognize and encourage inventors with U.S. patents and enhance the visibility of academic technology and innovation.

As a member of the Class of 2023, Kaplan will be honored at the NAI’s annual meeting on June 18, 2024 in Raleigh, North ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists sharpen genetic maps to help pinpoint DNA changes that influence human health traits and disease risk

AI, monkey brains, and the virtue of small thinking

Firearm mortality and equitable access to trauma care in Chicago

Worldwide radiation dose in coronary artery disease diagnostic imaging

Heat and pregnancy

Superagers’ brains have a ‘resilience signature,’ and it’s all about neuron growth

New research sheds light on why eczema so often begins in childhood

Small models, big insights into vision

Finding new ways to kill bacteria

An endangered natural pharmacy hidden in coral reefs

The Frontiers of Knowledge Award goes to Charles Manski for incorporating uncertainty into economic research and its application to public policy analysis

Walter Koroshetz joins Dana Foundation as senior advisor

Next-generation CAR-T designs that could transform cancer treatment

As health care goes digital, patients are being left behind

A clinicopathologic analysis of 740 endometrial polyps: risk of premalignant changes and malignancy

Gibson Oncology, NIH to begin Phase 2 trials of LMP744 for treatment of first-time recurrent glioblastoma

Researchers develop a high-efficiency photocatalyst using iron instead of rare metals

Study finds no evidence of persistent tick-borne infection in people who link chronic illness to ticks

New system tracks blockchain money laundering faster and more accurately

In vitro antibacterial activity of crude extracts from Tithonia diversifolia (asteraceae) and Solanum torvum (solanaceae) against selected shigella species

Qiliang (Andy) Ding, PhD, named recipient of the 2026 ACMG Foundation Rising Scholar Trainee Award

Heat-free gas sensing: LED-driven electronic nose technology enhances multi-gas detection

Women more likely to choose wine from female winemakers

E-waste chemicals are appearing in dolphins and porpoises

Researchers warn: opioids aren’t effective for many acute pain conditions

Largest image of its kind shows hidden chemistry at the heart of the Milky Way

JBNU researchers review advances in pyrochlore oxide-based dielectric energy storage technology

Novel cellular phenomenon reveals how immune cells extract nuclear DNA from dying cells

Printable enzyme ink powers next-generation wearable biosensors

6 in 10 US women projected to have at least one type of cardiovascular disease by 2050

[Press-News.org] A malaria drug treatment could save babies’ livesHuman organ chip research shows that a common antimalarial combination could reverse the negative effects of malnutrition in the female digestive tract that lead to low birth weight infants