(Press-News.org)

Climate change is already harming agricultural yields and may one day pose a significant threat to the world’s food supply. Engineering more resilient crops, including those able to thrive in the face of drought or high soil salinity levels, is an increasingly urgent need.

A new study from the Keck School of Medicine of USC, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, reveals details about how plants regulate their responses to stress that may prove crucial to those efforts. Researchers found that plants use their circadian clocks to respond to changes in external water and salt levels throughout the day. That same circuitry—an elegant feedback loop controlled by a protein known as ABF3—also helps plants adapt to extreme conditions such as drought. The results were just published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The bottom line is plants are stuck in place. They can’t run around and grab a drink of water. They can’t move into the shade when they want to or away from soil that has excess salt. Because of that, they’ve evolved to use their circadian clocks to exquisitely measure and adapt to their environment,” said the study’s senior author, Steve A. Kay, PhD, University and Provost Professor of Neurology, Biomedical Engineering and Quantitative Computational Biology at the Keck School of Medicine and Director of the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience.

The findings build on a long line of research from Kay’s lab on the role of circadian clock proteins in both plants and animals. Clock proteins, which regulate biological changes over the course of the day, may provide a shrewd solution to an ongoing challenge in crop engineering. Creating drought-resistant plants is difficult, because plants respond to stress by slowing their own growth and development—an overblown stress response means an underperforming plant.

“There’s a delicate balance between boosting a plant’s stress tolerance while maximizing its growth and yield,” Kay said. “Solving this challenge is made all the more urgent by climate change.”

Finding the feedback loop

Previous plant biology research showed that clock proteins regulate about 90% of genes in plants and are central to their responses to temperature, light intensity and day length, including seasonal changes that determine when they flower. But one big outstanding question was whether and how clock proteins control the way plants handle changing water and soil salinity levels.

To explore the link, Kay and his team studied Arabidopsis, a plant commonly used in research because it is small, has a rapid life cycle, a relatively simple genome and shares common traits and genes with many agricultural crops. They created a library of all of the more than 2000 Arabidopsis transcription factors, which are proteins that control the way genes are expressed under different circumstances. Transcription factors can provide key insights about regulation of biological processes. The researchers then built a data analysis pipeline to analyze each transcription factor and search for associations.

“We got a really big surprise: that many of the genes the clock was regulating were associated with drought responses,” Kay said, particularly those controlling the hormone abscisic acid, a type of stress hormone that plants produce when water levels are very high or very low.

The analysis revealed that abscisic acid levels are controlled by clock proteins as well as the transcription factor ABF3 in what Kay calls a “homeostatic feedback loop.” Over the course of a day, clock proteins regulate ABF3 to help plants respond to changing water levels, then ABF3 feeds information back to clock proteins to keep the stress response in check. That same loop helps plants adapt when conditions become extreme, for instance during a drought. Genetic data also revealed a similar process for handling changes in soil salinity levels.

“What’s really special about this circuit is that it allows the plant to respond to external stress while keeping its stress response under control, so that it can continue to grow and develop,” Kay said.

Engineering better crops

The findings point to two new approaches that may help boost crop resilience. For one, agricultural breeders can search and select for naturally occurring genetic diversity in the circadian ABF3 circuit that gives plants a slight edge in responding to water and salinity stress. Even a small increase in resilience could substantially improve crop yield on a large scale.

Kay and his colleagues also plan to explore a genetic modification approach, using CRISPR to engineer genes that promote ABF3 in order to design highly drought-resistant plants.

“This could be a significant breakthrough in thinking about how to modulate crop plants to be more drought resistant,” Kay said.

About this research

In addition to Kay, the study's other authors are Tong Liang, Shi Yu, Yuanzhong Pan and Jiarui Wang from the Department of Neurology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California.

This work is supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [R37 GM067837].

END

Methods commonly used to measure poverty can lead to vastly different conclusions about who actually lives in poverty, according to a new Stanford University-led study. Based on household surveys in sub-Saharan Africa, the first-of-its-kind analysis, published Feb. 5 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, underscores the importance of accurately defining and measuring poverty. Its findings could help inform how governments, nonprofit organizations, and international development agencies allocate resources and evaluate the effectiveness of poverty-alleviation policies around the world.

“They say you can’t manage what ...

The workings of the ultrasonic warning sounds produced by the wings of a species of moth have been revealed by researchers at the University of Bristol.

Scientists recently discovered that moths of the genus Yponomeuta (so-called ermine moths) have evolved a very special acoustic defence mechanism against their echolocating predators—bats.

Ermine moths produce ultrasonic clicking sounds twice per wingbeat cycle using a minute corrugated membrane in their hindwing. Strikingly, these moths lack hearing organs and are therefore not aware of their unique defence mechanism, nor do they have the capability to control it using muscular ...

A new analysis by MIT researchers shows the places in the U.S. where jobs are most linked to fossil fuels. The research could help policymakers better identify and support areas affected over time by a switch to renewable energy.

While many of the places most potentially affected have intensive drilling and mining operations, the study also measures how areas reliant on other industries, such as heavy manufacturing, could experience changes. The research examines the entire U.S. on a county-by-county level.

“Our result ...

THIS PRESS RELEASE IS EMBARGOED UNTIL FEBRUARY 5, 2024 at 3:00 PM U.S. EASTERN TIME

Many Indigenous peoples and local communities around the world are leading very satisfying lives despite having very little money. This is the conclusion of a study by the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (ICTA-UAB), which shows that many societies with very low monetary income have remarkably high levels of life satisfaction, comparable to those in wealthy countries.

Economic growth is often prescribed as a sure way of increasing the well-being of people in low-income countries, and ...

Many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, are difficult to diagnose before symptoms begin to appear. However, disease-related biomarkers such as aggregated proteins called amyloids could provide important insight much earlier, if they can be readily detected. Researchers publishing in ACS Sensors have developed one such method using an array of sensor molecules that can light up amyloids. The tool could help monitor disease progression or distinguish between different ...

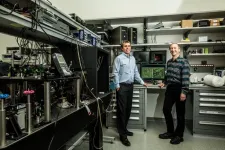

Janelia scientists and longtime collaborators Eric Betzig and Harald Hess will be inducted into the 2024 class of the National Inventors Hall of Fame for their invention of photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM), a pioneering imaging technology that enables scientists to image live cells in super-resolution to study biological structures and processes in unprecedented detail.

Betzig, a senior fellow at Janelia and an HHMI Investigator at the University of California, Berkeley, and Hess, a senior ...

Violence spreads in a contagious way like a disease among members of the Italian mafia, a new study shows.

Researchers have found committing violent acts with others increases the likelihood people in these groups will go on to carry out more violent offences in the future.

The analysis of the criminal careers of organised crime offenders shows previous violence has a “persistent and long-lasting” impact on their behaviour.

Prior violent co-offending has a greater impact than prior violent solo offending on the probability of future violence. Prior violent co-offending increases the probability ...

Petrina Kamya, PhD, Head of AI Platforms and President of Insilico Medicine Canada, will present at the BIO CEO & Investor Conference happening Feb. 26-27 at the New York Marriott Marquis in New York City. Dr. Kamya will speak as part of the panel “AI within Biopharma: Separating Value from Hype,” on Feb. 27, 1pm ET along with Michael Nally, CEO of Generate: Biomedicines and Liz Schwarzbach, PhD, CBO of BigHat Biosciences.

The session will look at how the latest artificial intelligence (AI) tools – including generative AI and large language models – ...

“[...] fruitful efforts to bring more drugs from bench to bedside could only be possible if we do not leave them ‘midway’!”

BUFFALO, NY- February 5, 2024 – A new editorial paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 15 on January 24, 2024, entitled, “The fate of drug discovery in academia; dumping in the publication landfill?”

In this new editorial, researchers Uzma Saqib, Isaac S. Demaree, Alexander G. Obukhov, Mirza S. Baig, Amiram Ariel, and Krishnan Hajela, from Devi Ahilya Vishwavidyalaya, Indore, discuss drug discovery—a tedious process that is time consuming in both divulging whether a molecule is efficacious and specific in hitting ...

In a warming climate, meltwater from Antarctica is expected to contribute significantly to rising seas. For the most part, though, research has been focused on West Antarctica, in places like the Thwaites Glacier, which has seen significant melt in recent decades.

In a paper published Jan. 19 in Geophysical Research Letters, researchers at Stanford have shown that the Wilkes Subglacial Basin in East Antarctica, which holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by more than 10 feet, could be closer to runaway melting than anyone realized.

“There hasn’t been much analysis in this region – there’s huge ...