(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA (February 20, 2024)—Surveys show most men in the United States are interested in using male contraceptives, yet their options remain limited to unreliable condoms or invasive vasectomies. Recent attempts to develop drugs that block sperm production, maturation, or fertilization have had limited success, providing incomplete protection or severe side effects. New approaches to male contraception are needed, but because sperm development is so complex, researchers have struggled to identify parts of the process that can be safely and effectively tinkered with.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have found a new method of interrupting sperm production, which is both non-hormonal and reversible. The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on February 20, 2024, implicates a new protein complex in regulating gene expression during sperm production. The researchers demonstrate that treating male mice with an existing class of drugs, called HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitors, can interrupt the function of this protein complex and block fertility without affecting libido.

“Most experimental male birth control drugs use a hammer approach to blocking sperm production, but ours is much more subtle,” says senior author Ronald Evans, professor, director of the Gene Expression Laboratory, and March of Dimes Chair in Molecular and Developmental Biology at Salk. “This makes it a promising therapeutic approach, which we hope to see in development for human clinical trials soon.”

The human body produces several million new sperm per day. To do this, sperm stem cells in the testes continuously make more of themselves, until a signal tells them it’s time to turn into sperm—a process called spermatogenesis. This signal comes in the form of retinoic acid, a product of vitamin A. Pulses of retinoic acid bind to retinoic acid receptors in the cells, and when the system is aligned just right, this initiates a complex genetic program that turns the stem cells into mature sperm.

Salk scientists found that for this to work, retinoic acid receptors must bind with a protein called SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors). SMRT then recruits HDACs, and this complex of proteins goes on to synchronize the expression of genes that produce sperm.

Previous groups have tried to stop sperm production by directly blocking retinoic acid or its receptor. But retinoic acid is important to multiple organ systems, so interrupting it throughout the body can lead to various side effects—a reason many previous studies and trials have failed to produce a viable drug. Evans and his colleagues instead asked whether they could modulate one of the molecules downstream of retinoic acid to produce a more targeted effect.

The researchers first looked at a line of genetically engineered mice that had previously been developed in the lab, in which the SMRT protein was mutated and could no longer bind to retinoic acid receptors. Without this SMRT-retinoic acid receptor interaction, the mice were not able to produce mature sperm. However, they displayed normal testosterone levels and mounting behavior, indicating that their desire to mate was not affected.

To see whether they could replicate these genetic results with pharmacological intervention, the researchers treated normal mice with MS-275, an oral HDAC inhibitor with FDA breakthrough status. By blocking the activity of the SMRT-retinoic acid receptor-HDAC complex, the drug successfully stopped sperm production without producing obvious side effects.

Another remarkable thing also happened once the treatment was stopped: Within 60 days of going off the pill, the animals’ fertility was completely restored, and all subsequent offspring were developmentally healthy.

The authors say their strategy of inhibiting molecules downstream of retinoic acid is key to achieving this reversibility.

Think of retinoic acid and the sperm-producing genes as two dancers in a waltz. Their rhythm and steps need to be coordinated with each other for the dance to work. But if you throw something in that makes the genes miss a step, the two are suddenly out of sync and the dance falls apart. In this case, the HDAC inhibitor causes the genes’ misstep, halting the dance of sperm production.

However, if the dancer can find its footing and get back in step with its partner, the waltz can resume. In the same way, the authors say that removing the HDAC inhibitor allows the sperm-producing genes to get back in sync with the pulses of retinoic acid, turning sperm production back on as desired.

“It’s all about timing,” says co-author Michael Downes, a senior staff scientist in Evans’ lab. “When we add the drug, the stem cells fall out of sync with the pulses of retinoic acid, and sperm production is halted, but as soon as we take the drug away, the stem cells can reestablish their coordination with retinoic acid and sperm production will start up again.”

The authors say the drug doesn’t damage the sperm stem cells or their genomic integrity. While the drug was present, the sperm stem cells simply continued regenerating as stem cells, and when the drug was later removed, the cells could regain their ability to differentiate into mature sperm.

“We weren’t necessarily looking to develop male contraceptives when we discovered SMRT and generated this mouse line, but when we saw that their fertility was interrupted, we were able to follow the science and discover a potential therapeutic,” says first author Suk-Hyun Hong, a staff researcher in Evans’ lab. “It’s a great example of how Salk’s foundational biological research can lead to major translational impact.”

Other authors include Glenda Castro, Dan Wang, Russell Nofsinger, Annette R. Atkins, and Ruth T. Yu of Salk, Maureen Kane, Alexandra Folias, and Joseph L. Napoli of UC Berkeley, Paolo Sassone-Corsi of UC Irvine, Dirk G. de Rooij of Utrecht University, and Christopher Liddle of the University of Sydney.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA265762 and CA220468) and the Next Generation Sequencing and Flow Cytometry Cores at Salk, funded by the Salk Cancer Center (NCI grant NIH-NCI CCSG: P30 014195).

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology, and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge. Learn more at www.salk.edu.

END

Salk scientists discover new target for reversible, non-hormonal male birth control

Oral administration of HDAC inhibitor blocked sperm production and fertility in mice without affecting libido

2024-02-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Unlike men, for professional women, having high-status connections can backfire

2024-02-20

Women working in organizations are frequently encouraged to cultivate connections to high-status individuals based on a prominent social network theory. But new research conducted in China and the United States suggests that having high-status connections can backfire for women.

The study, by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Michigan, appears in Organizational Science.

“Our findings reveal a social-network dilemma for women that is contrary to a widely accepted belief that women should build their network with high-status individuals,” said Catherine Shea, Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior and Theory at Carnegie Mellon's Tepper School ...

Time watching videos may stunt toddler language development, but it depends on why they're watching

2024-02-20

DALLAS (SMU) – A new study from SMU psychologist Sarah Kucker and colleagues reveals that passive video use among toddlers can negatively affect language development, but their caregiver’s motivations for exposing them to digital media could also lessen the impact.

Results show that children between the ages of 17 and 30 months spend an average of nearly two hours per day watching videos – a 100 percent increase from prior estimates gathered before the COVID pandemic. The research reveals a negative association between high levels of digital media watching and children’s vocabulary development.

Children exposed to videos ...

SwRI to host second Automotive Corrosion Symposium

2024-02-20

SAN ANTONIO — February 20, 2024 —Southwest Research Institute will host its second Automotive Corrosion Symposium in Detroit April 11-12. The event, first held in 2022, is designed to foster communication among corrosion experts from within automotive original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) as well as material, paint and other automotive suppliers over a wide spectrum of industry-identified corrosion issues.

“Corrosion is a concern within the automotive industry, not just for cosmetic reasons, but because it can affect functionality and safety,” said SwRI Staff Engineer James Dante, one of the organizers ...

Rutgers professor of computer science is named Sloan Fellow

2024-02-20

A Rutgers professor who studies and improves the design of algorithms – human-made instructions computers follow to solve problems and perform computations – has been selected to receive a 2024 Sloan Research Fellowship.

Aaron Bernstein, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, was named one of 126 researchers drawn from a select group of 53 institutions in the U.S. and Canada. The award honors extraordinary creativity, innovation and the potential to become a scientific ...

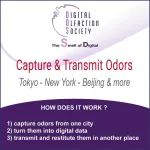

Challenge Announcement: Global Initiative to Digitalize Scents by the Digital Olfaction Society Revolutionary Scent Digitalization Challenge 2025: Capturing Aromas to Reproduce Anywhere

2024-02-20

Tokyo, The Digital Olfaction Society (DOS) announces a global initiative for 2025, aiming to digitize and transmit scents from various locations around the world for reproduction in Tokyo. This project intends to capture a wide range of fragrances representing the cultural diversity of the globe, leading to a significant development in Tokyo.

Invitation for Worldwide Participation

DOS invites teams from around the world to participate in this initiative. Whether located in major cities such as Berlin, New York, Dubai, or any place with a distinctive aroma, contributions ...

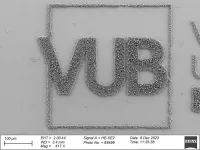

VUB researchers assemble patterns of micro- and nanoparticles

2024-02-20

Researchers from the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Riga Technical University and the MESA+ Institute at the University of Twente have succeeded in arranging very small particles (10 µm to 500 nm, 10 to 100 times thinner than a human hair) in a thin layer without using solvents. This is a hugely important first step towards developing a new generation of sensors and electronics for a wide range of applications.

“Common methods based on crystallising solutions are ...

Ancient DNA reveals Down syndrome in past human societies

2024-02-20

By analysing ancient DNA, an international team of researchers have uncovered cases of chromosomal disorders, including what could be the first case of Edwards syndrome ever identified from prehistoric remains.

The team identified six cases of Down syndrome and one case of Edwards syndrome in human populations that were living in Spain, Bulgaria, Finland, and Greece from as long ago as 4,500 years before today.

The research indicated that these individuals were buried with care, and often with special grave goods, showing that they were appreciated as members of their ancient societies.

The global collaborative study, led by first author Dr ...

Smiling is the secret to seeing happiness, new research reveals

2024-02-20

Smiling for just a split second makes people more likely to see happiness in expressionless faces, new University of Essex research has revealed.

The study led by Dr Sebastian Korb, from the Department of Psychology, shows that even a brief weak grin makes faces appear more joyful.

The pioneering experiment used electrical stimulation to spark smiles and was inspired by photographs made famous by Charles Darwin.

A painless current manipulated muscles momentarily into action – ...

Antil studying efficient algorithms for optimization problems with PDE constraints

2024-02-20

Harbir Antil, Professor, Mathematical Sciences; Director, Center for Mathematics and Artificial Intelligence (CMAI), received funding for the project: “Efficient Algorithms for Optimization Problems with PDE Constraints.”

Antil and his collaborators are examining generic optimization problems constrained by partial differential equations (PDEs) with or without uncertainty. In case of uncertainty, a risk-averse optimization framework will be developed. Decomposition and Compression techniques will be utilized to overcome the high computational costs. Several applications in various disciplines such ...

Age-related changes in fibroblast cells promote pancreatic cancer growth and spread

2024-02-20

Older people may be at greater risk of developing pancreatic cancer and have poorer prognoses because of age-related changes in cells in the pancreas called fibroblasts, according to research led by investigators from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

The study, published online Feb. 8 in Cancer Research, provides clues as to why pancreatic cancer is more common and aggressive in older people. It may also help scientists develop ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] Salk scientists discover new target for reversible, non-hormonal male birth controlOral administration of HDAC inhibitor blocked sperm production and fertility in mice without affecting libido