(Press-News.org) Researchers have shown that inedible species of butterfly that mimic each others’ colour patterns have also evolved similar flight behaviours to warn predators and avoid being eaten.

It is well known that many inedible species of butterfly have evolved near identical colour patterns, which act as warning signals to predators so the butterflies avoid being eaten.

Researchers have now shown that these butterflies have not only evolved similar colour patterns, but that they have also evolved similar flight behaviours, which together make a more effective warning signal to predators.

Using high-speed video footage to record the flight of wild butterflies in South America, researchers at the University of York measured the wing beat frequency and wing angles of 351 butterflies, representing 38 species each belonging to one of 10 distinct colour pattern mimicry groups.

Using this dataset they investigated how the flight patterns of butterflies are related to factors such as habitat, wing shape, temperature and which colour pattern mimicry group the butterfly belongs to see which elements most heavily affected flight behaviour.

Although the species habitat and wing shape were expected to have the greatest influence on flight behaviour, the researchers found that in fact the biggest determinant of flight behaviour was the colour pattern mimicry group a butterfly belonged to.

This means that distantly-related butterflies belonging to the same colour pattern mimicry group have more similar flight behaviour than closely-related species that display different warning coloration. To a predator, the butterflies would not only look the same through their colour patterns, but would also move in the same way.

Edd Page, PhD student from the Department of Biology at the University of York and one of the lead authors of the study, said: “From an evolutionary perspective it makes sense to share the colour pattern between species, to reduce the individual cost of educating predators to the fact that they don’t taste nice!

“Once a predator has tasted one, the visual clues on others indicate that they too are also inedible, but flight patterns are more complex and are influenced by several other factors such as the air temperature and the habitat the species fly in.

“We wanted to see whether flight corresponded to colour - could predators be driving the mimicry of flight as well as colour patterns? We were surprised to find just how strong and widespread the behavioural mimicry is.”

The team looked specifically at a tribe of butterflies called the Heliconiini, which have around 100 species and subspecies distributed around the Neotropics, each belonging to one of several distinct colour pattern mimicry groups.

They also investigated a few species from the ithomiine butterfly tribe, which split from the Heliconiini about 70 million years ago, yet some of whom have very similar ‘Tiger’ colour patterns.

Edd said: “Sharing flight behaviour across multiple species seems to reinforce this ‘don’t eat me’ message. It is fascinating that this behaviour has evolved between distant relatives over a long period of time, but we can also see flight behaviour diverging between differently patterned populations within a species over a relatively short period of time too.

Professor Kanchon Dasmahapatra, from the University of York’s Department of Biology, said: “The extent of flight mimicry in this group of butterflies is amazing. It is a great example of how evolution shapes behaviour, with selection from predators driving subtle changes which enhance the survival of individuals.

“The challenge and interest now is to identify the genes causing these changes, which will tell us how such behavioural mimicry evolves.”

The article is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

END

Butterflies mimic each other’s flight behaviour to avoid predators

2024-02-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

What math tells us about social dilemmas

2024-02-26

Human coexistence depends on cooperation. Individuals have different motivations and reasons to collaborate, resulting in social dilemmas, such as the well-known prisoner's dilemma. Scientists from the Chatterjee group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) now present a new mathematical principle that helps to understand the cooperation of individuals with different characteristics. The results, published in PNAS, can be applied to economics or behavioral studies.

A group of neighbors shares a driveway. Following a heavy snowstorm, the entire driveway is covered in snow, requiring clearance for daily activities. ...

Protecting fish doesn’t have to mean neglecting people, study concludes

2024-02-26

BEAUFORT, N.C. –With fish stocks declining globally, more than 190 countries recently made a commitment to protect about a third of the world’s oceans within “Marine Protected Areas,” or MPAs by the year 2030. But these designated areas of the ocean where fishing is either regulated or outright banned can come at a huge cost to some coastal communities, according to a new analysis.

To help prepare for the expansion of MPAs, an international team of researchers from Duke University, Florida State ...

What will it take for China to reach carbon neutrality by 2060?

2024-02-26

To become carbon neutral by 2060, as mandated by President Xi Jinping, China will have to build eight to 10 times more wind and solar power installations than existed in 2022. Reaching carbon neutrality will also require major construction of transmission lines.

China land use policies will also have to be more coordinated and focused on a nation-wide scale rather than be left to ad hoc decisions by local governments. That’s because 80% of solar power and 55% of wind power will have to be built within 100 miles of major population centers.

These are the conclusions of a new study from ...

A new theoretical development clarifies water's electronic structure

2024-02-26

There is no doubt that water is significant. Without it, life would never have begun, let alone continue today – not to mention its role in the environment itself, with oceans covering over 70% of Earth.

But despite its ubiquity, liquid water features some electronic intricacies that have long puzzled scientists in chemistry, physics, and technology. For example, the electron affinity, i.e. the energy stabilization undergone by a free electron when captured by water, has remained poorly characterized from an experimental ...

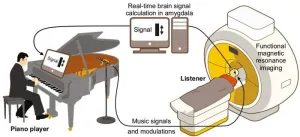

Live music emotionally moves us more than streamed music

2024-02-26

How does listening to live music affect the emotional center of our brain? A study carried out at the University of Zurich has found that live performances trigger a stronger emotional response than listening to music from a device. Concerts connect performers with their audience, which may also have to with evolutionary factors.

Music can have a strong effect on our emotions. Studies have shown that listening to recorded music stimulates emotional and imaginative processes in our brain. But what happens when we listen to music in a live setting, for example at a music festival, at the opera or a folk concert? ...

Detroit research team to develop novel strategies to identify genetic contributions to cancer risk and overcome barriers to genetic testing for African Americans

2024-02-26

DETROIT – A team of researchers from Wayne State University and the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute has received a five-year, $9.6 million grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health for the study “Genetic Variation in Cancer Risk and Outcomes in African Americans.” This is a Program Project Grant that includes three large studies. The team will work to improve the identification and clinical management of hereditary and multiple primary cancers in African Americans, a population that is currently underrepresented in genetic research.

According to Ann Schwartz, Ph.D., principal investigator of the project, professor and ...

Vaping can increase susceptibility to infection by SARS-CoV-2

2024-02-26

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Vapers are susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that spreads COVID-19 and continues to infect people around the world, a University of California, Riverside, study has found.

The liquid used in electronic cigarettes, called e-liquid, typically contains nicotine, propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and flavor chemicals. The researchers found propylene glycol/vegetable glycerin alone or along with nicotine enhanced COVID-19 infection through different mechanisms.

Study results appear in the American Journal of Physiology.

The researchers ...

Dissecting the roles for excitatory and inhibitory neurons in STXBP1 encephalopathy

2024-02-26

A recent study from Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital has discovered inhibitory and excitatory neurons play distinct roles in the pathogenesis of STXBP1 encephalopathy, one of the top five causes of pediatric epilepsies and among the most frequent causes of neurodevelopmental disorders. This early-onset disorder is caused by spontaneous mutations in the syntaxin-binding protein 1 (STXBP1) gene. While STXBP1 gene variants impair both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, this study led by Dr. Mingshan Xue, associate professor at Baylor and principal investigator at the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (Duncan ...

Boston College biologist awarded $2.5-million NIH grant to explore the role of viral insulins and potential applications to cancers

2024-02-26

Chestnut Hill, Mass (2/26/2024) – Boston College Assistant Professor of Biology Emrah Altindis has been awarded a five-year, $2.5-million grant from the National Institutes of Health to study viral insulins and mechanisms related to IGF-1 receptor protein inhibition and its potential applications in cancer treatment.

Altindis said he and the researchers in his lab will use the grant to learn more about how to use specific viral insulins – particularly insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) – to inhibit IGF-1 receptor action, which is increased in a range ...

New clinical practice guideline provides evidence-based recommendations for immunotherapy for inhalant allergy

2024-02-26

ALEXANDRIA, VA —The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation published the Clinical Practice Guideline: Immunotherapy for Inhalant Allergy today in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. This clinical practice guideline identifies quality improvement opportunities and provides clinicians trustworthy, evidence-based recommendations on the management of inhalant allergies with immunotherapy, supporting them to provide enhanced care to patients aged 5 years and older who are experiencing symptoms from inhalant allergies.

“More ...