(Press-News.org) When you walk into your kitchen in the morning, you easily orient yourself. To make coffee, you approach a specific location. Maybe you step into the pantry to grab a quick breakfast and then head to your car to drive to your workplace.

How these apparently simple tasks happen is of major interest to neuroscientists at Baylor College of Medicine, Stanford University and collaborating institutions. Their work, published in the journal Science, has significantly improved our understanding of how this occurs by revealing a mechanism at the brain cell level that mediates how an animal moves about in the environment.

“It’s been known that animals and people can find their way in the environment thanks to the hippocampus, a brain region that forms a representation, a sort of a map of the environment that lets us know where we are,” said co-first author Dr. Barna Dudok, assistant professor of neurology and a McNair Scholar at Baylor. Dudok also is co-corresponding author of this work.

Numerous brain cells or neurons in the hippocampus work together to create the map of a particular environment, say the kitchen in your home. Scientists know that each of these neurons, called place cells, becomes activated only in a specific place in the environment. For instance, the location of the coffee pot activates one place cell, and the pantry activates another.

“Place cells help a person know where he or she is,” Dudok said. “When a person walks through a particular area of the environment, specific place cells are activated and others will activate when the person moves to a different area. In the current study, we worked with mice and showed what happens at the neuronal level when an animal is orienting itself in the environment. Specifically, we demonstrate a role for the molecular messengers called endocannabinoids in the activity of place cells.”

When place cells in the hippocampus become activated, they release endocannabinoids, which are lipids, fat-like molecules that mediate communication between one neuron and the next.

“Until now, all the details of how endocannabinoids work have been described in brain slices. In this study, we had for the first time the methods to record these signals at high resolution in a living animal,” Dudok said.

The researchers used a molecular tool that turns endocannabinoid signals into fluorescence and a microscope to image the brain of a mouse as it was running on a treadmill.

“It was very rewarding to me when I analyzed those images and realized that there are endocannabinoid signals that I can detect that change when a mouse moves in the environment,” Dudok said. “I have been studying this pathway for a long time and it always was something we can pick up on brain slices. To actually see it happening in the brain of an active animal was very exciting.”

Surprisingly, activated single place cells release endocannabinoids and the signals go away in a matter of seconds. “Before, people suspected that this would be a slow signal that spreads to various cells, but it seems that it is a fast signal that is very specific to individual cells and contributes to its ability to encode information about the animal’s location,” Dudok said.

Supporting the importance of endocannabinoid signaling in animal orientation, the researchers found that disrupting the mechanism by eliminating the endocannabinoid receptor in neurons also disrupted the circuit in the hippocampus that helps the animal know its location, and consequently the hippocampus forms a less accurate map.

This work also has implications for human neurological disorders. “Our group and others showed earlier that epileptic seizures trigger the release of endocannabinoids. We would like to understand if this contributes to memory problems of people with epilepsy,” Dudok said. “This could lead to ways to prevent or revert the reorganization of the endocannabinoid signaling pathway in epilepsy and potentially improve cognitive comorbidities in this condition.”

Co-first author Linlin Z. Fan, Jordan S. Farrell, Shreya Malhotra, Jesslyn Homidan, Doo Kyung Kim, Celestine Wenardy, Charu Ramakrishnan, Yulong Li, Karl Deisseroth and Ivan Soltesz also contributed to this work. The authors are affiliated with one or more of the following institutions: Baylor College of Medicine, Stanford University, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Peking University and Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health. Dudok is a McNair Scholar supported by the McNair Medical Institute at The Robert and Janice McNair Foundation.

###

END

Researchers reveal mechanism of how the brain forms a map of the environment

2024-02-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Improving energy security with policies focused on demand-side solutions

2024-02-29

Governments typically rely on policies focused on energy supply to enhance energy security, ignoring demand-side options. Current indicators and indexes that measure energy security focus mostly on energy supply. This aligns with the International Energy Agency’s view, which defines energy security only in terms of security of supply. However, this approach does not fully capture the extent of vulnerability for states, businesses, and individuals during an energy crisis.

“Energy security assessments also need to reflect how vulnerable countries, firms, and households are to energy ...

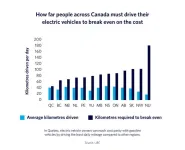

Driving an electric car is cheaper in some parts of Canada than others

2024-02-29

Electric vehicles are a critical part of Canada’s climate strategy, but a new University of British Columbia study highlights how it’s cheaper in some regions than others to drive electric—making it more challenging for certain households to make the switch.

Location, location, location

The researchers analyzed how far people need to drive their electric car to break even on the cost, factoring in the impacts of tax rebates and tax rates, charging costs, typical distance households travel in a region, and electricity ...

Emergency atmospheric geoengineering wouldn’t save the oceans

2024-02-29

WASHINGTON — Climate change is heating the oceans, altering currents and circulation patterns responsible for regulating climate on a global scale. If temperatures dropped, some of that damage could theoretically be undone. But employing “emergency” atmospheric geoengineering later this century in the face of continuous high carbon emissions would not be able to reverse changes to ocean currents, a new study finds. This would critically curtail the intervention’s potential effectiveness ...

New model of key brain tumor feature could help scientists understand how to develop new treatments

2024-02-29

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — Researchers at the University of Michigan Health Rogel Cancer Center are exploiting a unique biological feature of glioblastoma to gain a better understanding of how this puzzling brain cancer develops and how to target new treatments against it.

The team, led by senior author Pedro Lowenstein, M.D., Ph.D., Richard Schneider Collegiate Professor of Neurosurgery at Michigan Medicine, had previously identified oncostreams as a key feature in glioblastoma development and in more aggressive disease. These highly active, elongated, spindle-like cells ...

Study: Mutations in hereditary Alzheimer’s disease damage neurons without ‘usual suspect’ amyloid plaques

2024-02-29

LAWRENCE — A University of Kansas study of rare gene mutations that cause hereditary Alzheimer's disease shows these mutations disrupt production of a small sticky protein called amyloid.

Plaques composed of amyloid are notoriously found in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease and have long been considered responsible for the inexorable loss of neurons and cognitive decline. Using a model species of worm called C. elegans that’s often used in labs to study diseases at the molecular level, the research team came to the surprising conclusion that the stalled process of amyloid production — not the amyloid itself — can trigger loss of critical ...

Rice lab finds better way to handle hard-to-recycle material

2024-02-29

HOUSTON – (Feb. 29, 2024) – Glass fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP), a strong and durable composite material, is widely used in everything from aircraft parts to windmill blades. Yet the very qualities that make it robust enough to be used in so many different applications make it difficult to dispose of ⎯ consequently, most GFRP waste is buried in a landfill once it reaches its end of life.

According to a study published in Nature Sustainability, Rice University researchers and collaborators have developed a new, energy-efficient upcycling method to transform glass fiber-reinforced plastic ...

Ice shell thickness reveals water temperature on ocean worlds

2024-02-29

ITHACA, N.Y. – Cornell University astrobiologists have devised a novel way to determine ocean temperatures of distant worlds based on the thickness of their ice shells, effectively conducting oceanography from space.

Available data showing ice thickness variation already allows a prediction for the upper ocean of Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, and a NASA mission’s planned orbital survey of Europa’s ice shell should do the same for the much larger Jovian moon, enhancing the mission’s findings about whether it could support ...

Garrett Isaac Neubauer Center for Cardiovascular Innovation launches at Columbia

2024-02-29

NEW YORK, NY (February 29, 2024)--Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) today announced the launch of a new center for pediatric cardiovascular innovation, made possible through a visionary gift by Lawrence Neubauer. The mission of the new center is to improve outcomes for patients through groundbreaking research and care and to define the next cures for and future practice in congenital heart disease (CHD)—here and across the world.

In recognition of the transformative generosity of Lawrence Neubauer, the center will be named the Garrett Isaac Neubauer Center for Cardiovascular ...

MSU co-authored study: 10 insights to reduce vaccine hesitancy on social media

2024-02-29

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Effective population level vaccination campaigns are fundamental to public health. Countercampaigns, which are as old as the first vaccines, can disrupt uptake and threaten public health globally.

Even before March 2020, vaccine hesitancy was directly linked to misinformation — false, inaccurate information promoted as factual — on social media. Once COVID-19 reached pandemic status, social media was acknowledged as the epicenter of information leading to vaccine hesitancy, which the World Health Organization, ...

New study: Deforestation exacerbates risk of malaria for most vulnerable children

2024-02-29

Malaria kills more than 600,000 people each year worldwide, and two thirds are children under age five in sub-Saharan Africa. Scientists have found a treatment that could prevent thousands of these deaths: trees. New research conducted at the University of Vermont (UVM) and published today in the journal GeoHealth suggests forests can provide natural protection against disease transmission, particularly for the most vulnerable children.

Malaria spreads through the bite of Anopheles mosquitoes. While malaria is a disease long associated with lower socioeconomic status, the UVM study links deforestation with higher risk of the disease, particularly for ...