(Press-News.org) March 1, 2024, Port St. Lucie, Fla: Cleveland Clinic researchers have discovered a key mechanism used by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), to induce cancer. The research points to effective new treatment options for KSHV-associated cancers, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and HHV8-associated multicentric Castleman disease.

“Our findings have significant implications: viruses cause between 10% to 20% of cancers worldwide, a number that is constantly increasing as new discoveries are made. Treating virus-induced cancers with standard cancer therapies can help shrink tumors that are already there, but it doesn’t fix the underlying problem of the virus,” said Jun Zhao, Ph.D., of Cleveland Clinic Florida Research & Innovation Center. “Understanding how pathogens transform a healthy cell into a cancer cell uncovers exploitable vulnerabilities and allows us to make and repurpose existing drugs that can effectively treat virus-associated malignancies.”

The Nature Communications study, led by Dr. Zhao, reveals that KSHV manipulates two human enzymes called CDK6 and CAD to reshape the way human cells produce new nucleotides - the building blocks of DNA and RNA - and process glucose. The changes to how infected cells grow and how KSHV persists put cells at a much higher risk of forming tumors and play a crucial role in causing cancer.

The team showed the virus activates a specific pathway driving cell metabolism and proliferation. Inhibiting this process with existing FDA-approved breast cancer drugs reduced KSHV replication, blocked lymphoma progression and shrunk existing tumors in preclinical models.

Like other herpesviruses, KSHV often has no symptoms initially and remains in the body after primary infection. The virus stays dormant, suppressed by the immune system. However, KSHV can reactivate when immunity is weakened – as in older people, those with HIV/AIDS, and transplant recipients. In these high-risk groups, the now active virus can trigger aggressive cancers.

KSHV-induced cancers are fast-acting, aggressive and difficult to treat. An estimated 10% of people in North America and Northern Europe have KSHV, but this ranges throughout the globe. More than 50% of individuals in parts of Northen Africa are estimated to have the virus. Experts estimate these rates are higher, as KSHV often goes undiagnosed because of lack of symptoms. These findings have implications that reach past KSHV; researchers can apply knowledge about KSHV to other cancer-associated viruses that might use the same process to cause cancer.

To understand the cells’ metabolic processes to uncover the virus’s vulnerabilities, Dr. Zhao collaborated with Michaela Gack, Ph.D., Scientific Director of the Florida Research & Innovation Center.

Rapidly replicating cancer cells reprogram metabolism to fuel growth. Meanwhile, most viruses cannot produce energy or necessary molecules on their own, so they rely on human cells to do the work for them. The team found that the virus takes over the host protein CDK6 and CAD, causing the infected cells to produce extra metabolites, which allows faster replication of the virus and an uncontrolled proliferation of the cells.

The research team treated pre-clinical models with a CDK6-blocking drug, Palbociclib, an FDA-approved breast cancer medication, as well as a compound targeting CAD. They saw significant decreases in tumor size and increases in cancer survival rates: most tumors virtually disappeared after about a month of treatment, and remaining tumors shrank around 80%. Survival increased to 100% for selected lymphoma cell lines.

Dr. Zhao and his team are working to better understand the connections among KSHV, CDK6/CAD pathway, and cancer formation. With the knowledge they obtain, they plan to implement and refine their experimental drug combinations for clinical trials.

“Cellular metabolism could be hijacked by both viruses and cancers for pathogenesis,” said Dr. Zhao. “By investigating these metabolic rewiring mechanisms, we aim to find the Achilles’ heel of cancer-causing viruses and non-viral cancers. I’m excited to see what the future of this work holds.”

END

Cleveland Clinic researchers uncover how virus causes cancer, point to potential treatment

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates a specific pathway to drive viral persistent infection and cell growth, paving the way for tumors to form

2024-03-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

SLU professor studies link between adversity, psychiatric and cognitive decline

2024-03-01

Saint Louis University associate professor of health management and policy in the College for Public Health and Social Justice, SangNam Ahn, Ph.D., recently published a paper in Journal of Clinical Psychology that examines the relationship between childhood adversity, and psychiatric decline as well as adult adversity and psychiatric and cognitive decline. His team discovered that just one instance of adversity in childhood can increase cases of mental illness later in life, and adverse events in adults can lead to a greater chance of both mental ...

Warwick to benefit from £2.5 million funding into “phenomenal” metamaterials

2024-03-01

A £2.5m grant will enable a new network driving research into metamaterials, headed up by a researcher from the University of Warwick.

Metamaterials have phenomenal potential. They are artificial 3D structures comprised of at least two different materials. This combination and the structure give metamaterials properties beyond those of the materials used to make them. These properties may be electromagnetic, acoustic, magnetic, mechanical/structural, thermal, or chemical.

Metamaterials could transform our economy in a digital age, helping to address society’s challenges by contributing to manufacturing in areas of sustainability, health care, ...

More schooling is linked to slowed aging and increased longevity

2024-03-01

Participants in the Framingham Heart Study who achieved higher levels of education tended to age more slowly and went on to live longer lives as compared to those who did not achieve upward educational mobility, according to a new study at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and The Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center. Upward educational mobility was significantly associated with a slower pace of aging and lower risk of death. The results are published online in JAMA Network Open.

The Framingham Heart Study is an ongoing observational study first initiated in 1948 that currently spans three generations.

The Columbia analysis is ...

Trends in recurring and chronic food insecurity among US families with older adults

2024-03-01

About The Study: The results of this study highlight how rates of recurring and chronic food insecurity among families with older adults rose substantially over the past 20 years. Monitoring national trends in food insecurity among older adults has direct programmatic and policy implications.

Authors: Cindy W. Leung, Sc.D., M.P.H., of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.5463)

Editor’s ...

Self-reported everyday functioning after COVID-19 infection

2024-03-01

About The Study: The findings of this study of 372 veterans suggest that the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on everyday function may occur via multiple pathways regardless of whether or not they had a documented infection with COVID-19. Future work with larger samples is needed to validate the estimated associations.

Authors: Theodore J. Iwashyna, M.D., Ph.D., of Ann Arbor VA in Ann Arbor, Michigan, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.0869)

Editor’s ...

The surprisingly complex inner workings of an endocrine tumor

2024-03-01

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) find that the cells that make up aldosterone-producing adenomas become more transcriptionally active and express higher levels of genes linked to hormone production over intratumoral differentiation.

Tokyo, Japan – There is strength in teamwork, and it turns out that this applies to tumors, too. Researchers from Japan have reported that different types of cells within a single benign tumor may work together to promote the tumor’s growth.

In a study published this ...

Safety assessments for older drivers would benefit from introducing spatial orientation tests

2024-03-01

Older drivers who have worse spatial orientation ability experience greater difficulty when making turns across oncoming traffic, according to new research from the University of East Anglia (UEA).

Spatial orientation skills are the combination of skills that enable us to mentally determine our position, or the position of our vehicle and other vehicles, relative to the environment.

Lead author Sol Morrissey, a PhD researcher at UEA’s Norwich Medical School, said: “Driving safety is typically reduced in older adults due to changes that take place during ...

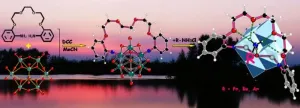

New type of metallacrown ether, polyoxometalatocrown ether, opens research opportunities

2024-03-01

Crown ethers were discovered in 1967. They were then modified by adding a metal-containing unit creating metallacrown ethers. These metallacrown ethers have been the subject of intensive research. Depending on the molecular makeup of the metallacrown ethers and their resultant architecture, the properties and therefore the uses of the metallacrowns can change. They have many different uses currently, and ongoing studies continue to expand their application. Just a few of these include magnetic refrigeration, imaging agents—specifically as potential contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging—and single-molecular ...

A protective human monoclonal antibody targeting a conserved site of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants

2024-03-01

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has caused serious damage to public health and the global economy, and one strategy to combat COVID-19 has been the development of broadly neutralizing antibodies for prophylactic and therapeutic use. The most emergency-use authorized (EUA) therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, are more likely to lose their neutralizing activities as the viral epitopes (e.g. the receptor-binding domain, RBD) within spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 they target are more prone to mutate. By contrast, the S2 subunit of spike protein, has a much lower frequency of mutation than ...

Scientists reveal how our cells’ leaky batteries are making us sick

2024-03-01

Researchers have discovered how “leaky” mitochondria – the powerhouses of our cells – can drive harmful inflammation responsible for diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Scientists may be able to leverage the findings to develop better treatments for those diseases, improve our ability to fight off viruses and even slow aging.

The new discovery reveals how genetic material can escape from our cellular batteries, known as mitochondria, and prompt the body to launch a damaging immune response. By developing therapies to target this process, doctors may one day be able to stop the harmful inflammation ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

[Press-News.org] Cleveland Clinic researchers uncover how virus causes cancer, point to potential treatmentKaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates a specific pathway to drive viral persistent infection and cell growth, paving the way for tumors to form