(Press-News.org) Oil and gas operations across the United States are emitting more than 6 million tons per year of methane, the main component of natural gas and the most abundant greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide, according to Stanford-led research published March 13 in Nature.

These emissions, which result from both intentional vents and unintentional leaks, amount to $1 billion in lost commercial value for energy producers. The annual cost rises to $10 billion when researchers account for harm to the economy and human well-being caused by adding this amount of heat-trapping methane to Earth’s atmosphere.

The new emission and cost estimates are roughly three times the level predicted by the U.S. government. The results are based on approximately 1 million aerial measurements of U.S. wells, pipelines, storage, and transmission facilities in six of the nation’s most productive regions, including the Permian and Forth Worth in Texas and New Mexico; California’s San Joaquin basin; Colorado’s Denver-Julesburg basin; Pennsylvania’s section of the Appalachian basin; and Utah’s Uinta basin. In all, the infrastructure surveyed in this study accounts for 52% of U.S. onshore oil production and 29% of gas production.

Troubling trends

Emissions in three of the six regions were well above expected values. The New Mexico portion of the Permian Basin was by far the highest emitter, with nearly 10% of total methane volume produced in 2019 going straight to the atmosphere. Surveys of some other regions, however, revealed emission rates well below U.S. EPA Greenhouse Gas Inventory estimates based on national averages, suggesting that good practices can reduce emissions.

“Costs aside, the main message here is that some regions show emissions at rates well above those the government itself uses to estimate methane losses,” said senior study author Adam Brandt, an associate professor of Energy Science & Engineering at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “We hope this will spur government methane inventories toward greater incorporation of remote sensing data at the heart of those estimates.”

Methane breaks down faster than carbon dioxide, but it is about 80 times more powerful than CO2 when it comes to trapping heat during its first 20 years in our atmosphere. In that time frame, climate damage from the 6 million tons of annual methane emissions found in this study is roughly equivalent to a full year of carbon emissions from all fossil fuel use in Mexico.

Because methane can trap so much heat in the short term, accurate assessments of methane leaks are key to predicting the impacts of climate change that will be felt in our lifetime and verifying emissions reductions at a time when the U.S. and more than 100 other countries have pledged to cut emissions 30% below 2020 levels by 2030.

Eyes in the sky

By showing that leaks cost industry more than a billion dollars a year, the researchers hope to gain producers’ attention and motivate them to voluntarily stop emissions at their own facilities as a cost-saving measure. Additionally, the researchers say total costs from methane leaks and vents in the six-region study area are likely much higher, as the survey covered less than half of the facilities in the area.

The authors found fewer than two percent of emitters are responsible for 50 to 80% of emissions in all surveyed regions except for Colorado’s Denver-Julesburg basin and Utah’s Uinta basin. In terms of types of production facilities most likely to leak, the study noted that midstream infrastructure was responsible for about half of total emissions, which is higher than previous estimates. Midstream infrastructure includes gathering and transmission pipelines, compressor stations, and gas processing plants that shuttle gas from the wells to cities and towns.

“Solving the methane challenge is not quite as easy as simply finding and fixing a handful of leakers, as these stark numbers might suggest, but it does mean that efforts concentrated on relatively few operations could have considerable benefits,” said lead study author, Evan Sherwin, a research scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who worked on the research as a postdoctoral scholar in Brandt’s lab at Stanford.

Measurement matters

The research combined direct aerial measurements with an emissions simulation tool developed in Brandt’s group at Stanford by study co-author Jeffrey Rutherford, PhD ’22, to estimate the emissions that would be too small for the aircraft to reliably detect. The companies Kairos Aerospace and Carbon Mapper provided two different but complementary approaches to measuring methane emissions from specific facilities via airplane-borne sensors.

Total estimated leaked emissions range from just less than one percent to as much as 9.6% of total volume, with an average of 3% across the surveyed regions. The federal government estimates that methane emissions from oil and gas facilities nationwide average roughly 1% of gas production. Sherwin noted that in the surveyed regions of Pennsylvania and Colorado, the team’s estimates were on par with or lower than estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“Climate change mitigation starts with better tracking of emissions, of course, but also accurate tracking of reduction efforts going forward,” Brandt said. “The method introduced here offers a path to combining measurements at several scales to greatly improve inventories that should lead us to much better tracking of those important reductions critical to national mitigation commitments.”

NOTE: Brandt and team have made their code available for download. Carbon Mapper data can be downloaded from the organization’s website. Anonymized data are also available, in certain cases, by request from Kairos Aerospace.

Brandt is also faculty director of the Stanford Natural Gas Initiative and a senior fellow at the Stanford Precourt Institute for Energy. Rutherford is now employed at Highwood Emissions Management. Additional Stanford co-authors include Energy Science & Engineering PhD students Zhan Zhang and Yuanlei (Yulia) Chen. Other coauthors are affiliated with Kairos Aerospace, Carbon Mapper, University of Arizona, and NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

This study was funded by the Stanford Natural Gas Initiative, NASA’s Carbon Monitoring System and Advanced Information System Technology programs, Carbon Mapper, RMI, the Environmental Defense Fund, the California Air Resources Board, the University of Arizona, the U.S. Climate Alliance, Arizona State University’s Global Airborne Observatory, and the Mark Martinez and Joey Irwin Memorial Public Projects Fund with the support of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Portions of this research were carried out under a contract with NASA.

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

END

Methane emissions from U.S. oil and gas operations cost the nation $10 billion per year

2024-03-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Explaining a supernova's 'string of pearls'

2024-03-13

Images

Physicists often turn to the Rayleigh-Taylor instability to explain why fluid structures form in plasmas, but that may not be the full story when it comes to the ring of hydrogen clumps around supernova 1987A, research from the University of Michigan suggests.

In a study published in Physical Review Letters, the team argues that the Crow instability does a better job of explaining the "string of pearls" encircling the remnant of the star, shedding light on a longstanding astrophysical mystery.

"The fascinating ...

Marine heat waves disrupt the ocean food web in the northeast Pacific Ocean

2024-03-13

NEWPORT, Ore. – Marine heat waves in the northeast Pacific Ocean create ongoing and complex disruptions of the ocean food web that may benefit some species but threaten the future of many others, a new study has shown.

The study, just published in the journal Nature Communications, is the first of its kind to examine the impacts of marine heat waves on the entire ocean ecosystem in the northern California Current, the span of waters along the West Coast from Washington to Northern California.

The researchers found that the biggest beneficiary of marine heat waves is gelatinous zooplankton – predominantly ...

The 11th World Congress on Microbiota Medicine critically evaluates probiotic supplementation strategies

2024-03-13

The International Society of Microbiota (ISM) announces its 11th World Congress, "Targeting Microbiota 2024", scheduled for October 14-15 at the Corinthia Palace in Malta. This event is set to highlight the latest research and developments in microbiotal medicine, emphasizing its impact on human health and its potential in shaping future medical treatment approaches.

Detailed Workshop: Probiotic Prescribing Practices dedicated to Medical Professionals

The congress will feature a critical workshop on October 15, titled “Probiotic Prescribing Practices: Empowering Medical Doctors for Improved Patient Health.” ...

Engineering Biology Research Consortium releases roadmap to mitigate, present and adapt to climate change

2024-03-13

Engineering Biology for Climate & Sustainability is the fifth technical roadmap developed by the Engineering Biology Research Consortium (EBRC) and represents the first dedicated to innovations and opportunities towards overcoming a significant global challenge. The roadmap targets and challenges are aligned and were drawn from existing climate and sustainability literature, particularly those focused on long-term impacts and opportunities, including reports from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The roadmap consists of six themes ...

Strengthening the partnership between humans and AI: the case of translators

2024-03-13

ChatGPT and its ability to hold conversations and produce written content have been the focus of a lot of attention in the last year in the field of technology and artificial intelligence. However, AI has been around for some time, helping us in all sorts of everyday tasks, from navigation systems to social network algorithms, not to mention machine translation. Ever since neural machine translation (NMT) systems began to be used on a widespread basis a few years ago, AI has seen exponential growth in its uptake in the translation industry. This has led to new challenges in the relationship between human and machine translators.

Today, the post-editing ...

Milk to the rescue for diabetics? Cow produces human insulin in milk

2024-03-13

An unassuming brown bovine from the south of Brazil has made history as the first transgenic cow capable of producing human insulin in her milk. The advancement, led by researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the Universidade de São Paulo, could herald a new era in insulin production, one day eliminating drug scarcity and high costs for people living with diabetes.

“Mother Nature designed the mammary gland as a factory to make protein really, really efficiently. We can take advantage ...

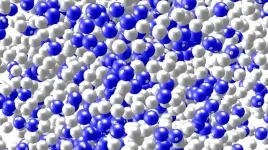

Molecular simulations of ammonia mixtures support search for renewable fuels

2024-03-13

Ammonia (NH3) is an important molecule with many applications. The end product of the famed Haber–Bosch process, it is commonly synthesized to capture nitrogen for fertilizers, and is used for refrigeration, in cleaning products, and in the production of pharmaceuticals. Recently, this modest molecule has also attracted interest as a potential resource for addressing one of today’s most pressing challenges — the need for reliable and abundant renewable fuels.

Ammonia is stable and safe ...

First recognition of self in the mirror is spurred by touch

2024-03-13

Most babies begin recognizing themselves in mirrors when they are about a year and half old. This kind of self-recognition is an important developmental milestone, and now scientists at The University of Texas at Austin have discovered a key driver for it: experiences of touch.

Their new study found babies who were prompted to touch their own faces developed self-recognition earlier than those who did not. The research was published this month in the journal Current Biology.

“This suggests that babies pulling ...

Dartmouth engineering team discovers new high-performance solar cell material

2024-03-13

A Dartmouth Engineering-led study published in Joule reported the discovery of an entirely new high-performance material for solar absorbers—the central part of a solar cell that turns light into electricity—that is stable and earth-abundant. The researchers used a unique high-throughput computational screening method to accelerate the discovery process and were able to quickly evaluate approximately 40,000 known candidate materials.

"This is the first example in the field of photovoltaics where a new material has been found through this type ...

Advancing toward wearable stretchable electronics

2024-03-13

Small wearable or implantable electronics could help monitor our health, diagnose diseases, and provide opportunities for improved, autonomous treatments. But to do this without aggravating or damaging the cells around them, these electronics will need to not only bend and stretch with our tissues as they move, but also be soft enough that they will not scratch and damage tissues.

Researchers at Stanford have been working on skin-like, stretchable electronic devices for over a decade. In a paper published ...