The researchers will present their results today at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Spring 2024 is a hybrid meeting being held virtually and in person March 17-21; it features nearly 12,000 presentations on a range of science topics.

“With some animals, the coat looks different in summer and winter,” says Taylor Millett, who is carrying out the research. A snowshoe hare turns white in winter and brown in summer, for instance. “But in the animals we’re studying, we’ve found that it's not just the outer coloring of the hair that's changing. The inner microscopic details are also changing to allow these animals to continue surviving in their environment.”

Millett, an undergraduate student in the mechanical engineering program at Utah Tech University, is being mentored by Wendy Schatzberg, an associate chemistry professor, and Samuel Tobler, a physics professor. Cristina De La Vieja Medina is another undergraduate working on the project.

Schatzberg and Tobler teach undergraduate students to use a scanning electron microscope (SEM), which bombards a sample with electrons to produce an image that clearly reveals microscopic details. “Once the students learn how to use the SEM to investigate small particles, we give them the freedom to study other samples that interest them,” Schatzberg says. “Taylor decided to pick animal hair. I never was particularly interested in animal hair until she brought it to our attention, but it’s fascinating.”

Millett, who describes herself as outdoorsy, had heard that the hair of pronghorn antelope is hollow, but nobody knew much more about it than that. “So I decided to cut it open and use the SEM to see what was going on,” she recalls. For context, the dimensions of a pronghorn antelope’s hair range from 5 to 15 centimeters (less than six inches) in length, depending on its location on the animal. The average diameter of the antelope hair is 440 micrometers.

She then asked her mentors if she could do additional studies. She chose big game animals, because previous research at other institutions had focused on domesticated animals such as sheep or llamas. “Nobody had branched out to wild animals because it's harder to get their hair,” Millett says.

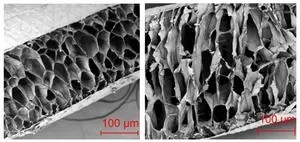

In addition to pronghorn antelope, she selected mule deer and Rocky Mountain elk — prey animals that can be found close to campus. She obtained winter and summer animal hair samples from a local wildlife taxidermist and from the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, which picks up animals that have been hit by cars. Millett and De La Vieja Medina sliced the hairs open, gold plated them to improve the SEM image resolution, and then examined and measured the spongy interior structures. These structures, consisting of a random collection of tiny hollow cavities, or air pockets, resemble messy honeycombs.

The students found that, in both summer and winter hairs, the air pockets near the perimeter of the hairs were much smaller than those in the core. In addition, winter hairs had larger air pockets than summer hairs in all three species. In mule deer, for example, winter air pockets had an average diameter of 26 micrometers, while summer air pockets averaged 13 micrometers in diameter. The core of the summer hair was, therefore, much more densely packed than the winter hair. “This is very intriguing, because those pockets create an insulative barrier that keeps the animals warm in winter,” Millett says.

To determine whether these findings apply to other animals, including predator species such as bears, mountain lions and bobcats, Millett is contacting zoos around the world for hair samples. The researchers also want to assess how geographic location and climate affect the results, Schatzberg notes. “Is it just our area that’s like this? And how much temperature difference between the seasons does it take? Sometimes up here we have a very large temperature difference between summer and winter,” she says. “So there are all these variables to examine.”

Millett is pondering how to apply the results. One potential application is synthetic insulation for houses and camping gear.

The research was funded by Utah Tech and the Utah NASA Space Grant Consortium.

Visit the ACS Spring 2024 program to learn more about this presentation, “Hollow hair and how its structure helps big game animals thermoregulate,” and more scientific presentations.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive news releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note to journalists: Please report that this research was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society. ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.

Follow us: X, formerly Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

Title

Hollow hair and how its structure helps big game animals thermoregulate

Abstract

This study delves into the intriguing world of hollow hair strands in animals, focusing on their role in thermoregulation, and the ability to maintain a stable body temperature in the face of fluctuating external conditions. While the Pronghorn antelope is widely known for having hollow hair strands among hunters and conservationists, little is known about their internal structure. Employing scanning electron microscopy (SEM), we explored the inner composition of these hollow hair strands and their contribution to thermoregulation.

Our investigation centered on several notable North American big game animals, including Mule deer, Rocky Mountain elk, and Pronghorn antelope, all of which exhibit a unique adaptation: the transition between summer and winter coats. Through SEM analysis, we measured and compared the winter and summer coats of these animals to gain insights into how they effectively regulate their body temperatures during the extremes of hot summers and cold winters. These seasonal changes manifest in alterations in fur and hair thickness and length.

Under the microscope, we unveiled the distinct topography of the inner structure of individual hair strands. Notably, our findings revealed that the inner hair structure contains larger hollow pockets in the winter coats of these animals. Our research thus sheds light on the role of these hollow structures in heat transfer and their pivotal contribution to the thermoregulation abilities of these remarkable creatures, expanding our understanding of their unique adaptations.

END