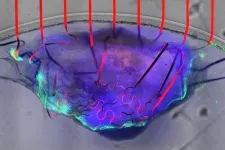

(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. – A team of engineers led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst and including colleagues from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) recently announced in the journal Nature Communications that they had successfully built a tissue-like bioelectronic mesh system integrated with an array of atom-thin graphene sensors that can simultaneously measure both the electrical signal and the physical movement of cells in lab-grown human cardiac tissue. In a research first, this tissue-like mesh can grow along with the cardiac cells, allowing researchers to observe how the heart’s mechanical and electrical functions change during the developmental process. The new device is a boon for those studying cardiac disease as well as those studying the potentially toxic side-effects of many common drug therapies.

Cardiac disease is the leading cause of human morbidity and mortality across the world. The heart is also very sensitive to therapeutic drugs, and the pharmaceutical industry spends millions of dollars in testing to make sure that its products are safe. However, ways to effectively monitor living cardiac tissue are extremely limited.

In part, this is because it is very risky to implant sensors in a living heart, but also because the heart is a complex kind of muscle with more than one thing that needs monitoring. “Cardiac tissue is very special,” says Jun Yao, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering in UMass Amherst’s College of Engineering and the paper’s senior author. “It has a mechanical activity—the contractions and relaxations that pump blood through our body—coupled to an electrical signal that controls that activity.”

But today’s sensors can typically only measure one characteristic at a time, and a two-sensor device that could measure both charge and movement would be so bulky as to impede the cardiac tissue’s function. Until now, there was no single sensor capable of measuring the heart’s dual properties without interfering with its functioning.

The new device is built of two critical components, explains lead author Hongyan Gao, who is pursuing his Ph.D. in electrical engineering at UMass Amherst. The first is a three-dimensional cardiac microtissue (CMT), grown in a lab from human stem cells under the guidance of co-author Yubing Sun, associate professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at UMass Amherst. CMT has become the preferred model for in vitro testing because it is the closest analog yet to a full-size, living human heart. However, because CMT is grown in a test tube, it has to mature, a process that takes time and can be easily disrupted by a clumsy sensor.

The second critical component involves graphene—a pure-carbon substance only one atom thick. Graphene has a few surprising quirks to its nature that make it perfect for a cardiac sensor. Graphene is electrically conductive, and so it can sense the electrical charges shooting through cardiac tissue. It is also piezoresistive, which means that as it is stretched—say, by the beating of a heart—its electrical resistance increases. And because graphene is impossibly thin, it can register even the tiniest flutter of muscle contraction or relaxation and can do so without impeding the heart’s function, all through the maturation process. Co-author Jing Kong, professor of electrical engineering at MIT, and her group supplied this critical graphene material.

“Although there have already been many applications for graphene, it is wonderful to see that it can be used in this critical need, which takes advantage of graphene’s different characteristics,” says Kong.

Gao, Yao and their colleagues then embedded a series of graphene sensors in a soft, stretchable porous mesh scaffold they developed that has close structural and mechanical properties to human tissue and which can be applied non-invasively to cardiac tissue.

“No one has ever done this before,” says Gao. “Graphene can survive in a biological environment without degrading for a very long time and not lose its conductivity, so we can monitor the CMT across its entire maturation process.”

“This is crucial for a number of reasons,” adds Yao. “Our sensor can give real-time feedback to scientists and drug researchers, and it can do so in a cost-effective way. We take pride in using the insights of electrical engineering to help build tools that can be useful to a wide range of researchers.”

In the future, Gao says, he hopes to be able to adapt his sensor to grander scales, even to in vivo monitoring, which would provide the best-possible data to help solve cardiac disease.

This research was supported by the Army Research Office, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Semiconductor Research Corporation, and the Link Foundation, as well as the Institute for Applied Life Sciences at UMass Amherst.

Contacts: Jun Yao, juny@umass.edu

Daegan Miller, drmiller@umass.edu

END

UMass Amherst engineers create bioelectronic mesh capable of growing with cardiac tissues for comprehensive heart monitoring

In a boon for medical researchers, new tool is the first that can measure both mechanical movement and electrical signal in vitro using a single sensor

2024-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers take major step toward developing next-generation solar cells

2024-03-21

The solar energy world is ready for a revolution. Scientists are racing to develop a new type of solar cell using materials that can convert electricity more efficiently than today’s panels.

In a new paper published February 26 in the journal Nature Energy, a University of Colorado Boulder researcher and his international collaborators unveiled an innovative method to manufacture the new solar cells, known as perovskite cells, an achievement critical for the commercialization of what ...

CUNY ISPH to launch next phase of community-based cohort study to track short- and long-term effects of multiple respiratory viruses

2024-03-21

The City University of New York (CUNY) Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health (ISPH) and the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy (CUNY SPH), in collaboration with Pfizer, are initiating a critical two-year prospective epidemiologic study in the spring of 2024 to track acute respiratory infections across the United States.

Project PROTECTS (Prospective Respiratory Outcomes from Tracking and Evaluating Community-based TeSting) builds on the CHASING COVID Cohort Study, which has monitored SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and ...

47th Annual UNC Lineberger Scientific Symposium: “Pancreatic Cancer: From Discovery to the Clinic”

2024-03-21

UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center is hosting its 47th annual scientific symposium, “Pancreatic Cancer: From Discovery to the Clinic,” on May 21-22 at the Friday Center for Continuing Education in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

The symposium is free and will feature 15 talks on the latest in pancreatic cancer basic, translational and clinical research by faculty at the University of North Carolina, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, University of Michigan ...

A new path to drug diversity

2024-03-21

Many important medicines, such as antibiotics and anticancer drugs, are derived from natural products from Bacteria. The enzyme complexes that produce these active ingredients have a modular design that makes them ideal tools for synthetic biology. By exploring protein evolution, a team led by Helge Bode from the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Marburg, Germany, has found new "fusion sites" that enable faster and more targeted drug development.

Industry often follows the assembly line principle: components are systematically assembled into complex products, with different production lines yielding different products. However, not humans are the ...

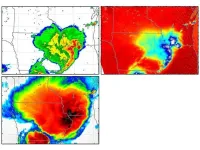

Satellite data assimilation improves forecasts of severe weather

2024-03-21

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — In 2020, a line of severe thunderstorms unleashed powerful winds that caused billions in damages across the Midwest United States. A technique developed by Penn State scientists that incorporates satellite data could improve forecasts — including where the most powerful winds will occur — for similar severe weather events.

The researchers reported in the journal Geophysical Research Letters that adding microwave data collected by low-Earth-orbiting satellites to existing computer weather forecast models produced more accurate forecasts of surface gusts in a case study of the 2020 Midwest ...

Morality among low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer survivors in the U.S.

2024-03-21

A new study has shown that overall and cause-specific mortality rates in individuals in the U.S. with low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) are low. The study is published in the peer-reviewed journal Thyroid®, the official journal of the American Thyroid Association® (ATA®). Click here to read the article now.

Cari Kitahara, PhD, from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and coauthors identified 51,854 individuals diagnosed with first primary DTC at low risk ...

Most detailed atlas to date of human blood stem cells could guide future leukemia care

2024-03-21

Thanks to an unusual application of game theory and machine learning technology, a large team of scientists led by experts at Cincinnati Children’s has published the world’s most detailed “atlas” of the many types of stem cells and early progenitors involved in producing human blood from diverse donors.

The team has identified more than 80 distinct subsets of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) – early-stage cells that kick off production of mature red cells, white cells ...

Novel method to measure root depth may lead to more resilient crops

2024-03-21

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — As climate change worsens global drought conditions, hindering crop production, the search for ways to capture and store atmospheric carbon causing the phenomenon has intensified. Penn State researchers have developed a new high-tech tool that could spur changes in how crops withstand drought, acquire nitrogen and store carbon deeper in soil.

In findings published in the January issue of Crop Science, they describe a process in which the depth of plant roots can be accurately estimated by scanning leaves with ...

Scientists develop catalyst designed to make ammonia production more sustainable

2024-03-21

Ammonia is one of the most widely produced chemicals in the world, and is used in a great many manufacturing and service industries. The conventional production technology is the Haber-Bosch process, which combines nitrogen gas (N2) and hydrogen gas (H2) in a reactor in the presence of a catalyst. This process requires high levels of temperature and pressure, resulting in substantial power consumption. Indeed, ammonia production is estimated to consume 1%-2% of the world’s electricity and to account for about 3% of global carbon emissions.

In pursuit of more sustainable alternatives, researchers affiliated with the Center for Development of Functional Materials (CDMF) ...

Forest, stream habitats keep energy exchanges in balance, global team finds

2024-03-21

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Forests and streams are separate but linked ecosystems, existing side by side, with energy and nutrients crossing their porous borders and flowing back and forth between them. For example, leaves fall from trees, enter streams, decay and feed aquatic insects. Those insects emerge from the waters and are eaten by birds and bats. An international team led by Penn State researchers has now found that these ecosystems appear to keep the energy exchanges in balance — a finding that the scientists called surprising.

Scientists ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

How many times will we fall passionately in love? New Kinsey Institute study offers first-ever answer

Bridging eye disease care with addiction services

Study finds declining perception of safety of COVID-19, flu, and MMR vaccines

The genetics of anxiety: Landmark study highlights risk and resilience

How UCLA scientists helped reimagine a forgotten battery design from Thomas Edison

Dementia Care Aware collaborates with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to advance age-friendly health systems

Growth of spreading pancreatic cancer fueled by 'under-appreciated' epigenetic changes

Lehigh University professor Israel E. Wachs elected to National Academy of Engineering

Brain stimulation can nudge people to behave less selfishly

Shorter treatment regimens are safe options for preventing active tuberculosis

How food shortages reprogram the immune system’s response to infection

The wild physics that keeps your body’s electrical system flowing smoothly

From lab bench to bedside – research in mice leads to answers for undiagnosed human neurodevelopmental conditions

More banks mean higher costs for borrowers

Mohebbi, Manic, & Aslani receive funding for study of scalable AI-driven cybersecurity for small & medium critical manufacturing

Media coverage of Asian American Olympians functioned as 'loyalty test'

University of South Alabama Research named Top 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025

Genotype-specific response to 144-week entecavir therapy for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B with a particular focus on histological improvement

[Press-News.org] UMass Amherst engineers create bioelectronic mesh capable of growing with cardiac tissues for comprehensive heart monitoringIn a boon for medical researchers, new tool is the first that can measure both mechanical movement and electrical signal in vitro using a single sensor