(Press-News.org) A new study conducted by researchers at Tampere University and Tampere University Hospital revealed how aberrant epigenetic regulation contributes to the development of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid (AT/RT) tumours, which are aggressive brain tumours that mainly affect young children. There is an urgent need for more research in this area as current treatment options are ineffective against these highly malignant tumours.

Most tumours take a long time to develop as harmful mutations gradually accumulate in cells’ DNA over time. AT/RT tumours are a rare exception, because the inactivation of one gene gives rise to this highly aggressive form of brain cancer.

AT/RT tumours are rare central nervous system embryonic tumours that predominantly affect infants and young children. On average, 73 people are diagnosed with AT/RT in the USA each year. However, AT/RT is the most common central nervous system tumour in children under one years old and accounts for 40-50% of diagnoses in this age group. The prognosis for AT/RT patients is grim, with a postoperative median survival of only 11-24 months.

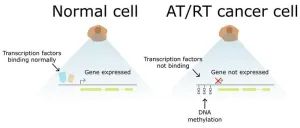

The collaborative study conducted by Tampere University and Tampere University Hospital examined how aberrant DNA methylation distorts cellular developmental trajectories and thereby contributes to the formation of AT/RT. DNA methylation is a process whereby methyl groups are added to the DNA strand. DNA methylation is one of the mechanisms that cells use to control gene expression, and methylation patterns change during normal brain development.

The new study showed that DNA methylation interferes with the activity of multiple regulators, which under normal circumstances regulate the differentiation and maturation of central nervous system cells during brain development. Disrupted cell differentiation promotes the abnormal, uncontrolled proliferation of cells that eventually form a tumour.

The study also found several genes that regulate cell differentiation or inhibit tumour development and are silenced in AT/RT together with increased DNA methylation. The findings will pave the way for a more detailed understanding of the epigenetic dysregulation mechanisms in AT/RT pathogenesis and enable researchers to identify which genes contribute to the malignant progression of the tumour.

“These results will provide deeper insights into the development of AT/RTs and their malignancy. In the future, the results will help to accelerate the discovery of new treatments for this aggressive brain tumour,” says Docent Kirsi Rautajoki from Tampere University.

At Tampere University, the research was mainly carried out by the research groups led by Kirsi Rautajoki and Professor Matti Nykter. The key partners from Tampere University Hospital included paediatrician, LM Kristiina Nordfors, neurosurgeon and Docent Joonas Haapasalo and neuropathologist and Docent Hannu Haapasalo.

END

New study sheds light on the mechanisms underlying the development of malignant pediatric brain tumors

2024-04-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Evolution's recipe book: How ‘copy paste’ errors cooked up the animal kingdom

2024-04-15

700 million years ago, a remarkable creature emerged for the first time. Though it may not have been much to look at by today’s standards, the animal had a front and a back, a top and a bottom. This was a groundbreaking adaptation at the time, and one which laid down the basic body plan which most complex animals, including humans, would eventually inherit.

The inconspicuous animal resided in the ancient seas of Earth, likely crawling along the seafloor. This was the last common ancestor of bilaterians, ...

Switch to green wastewater infrastructure could reduce emissions and provide huge savings according to new research

2024-04-15

Embargo: This journal article is under embargo until April 15 at 10 a.m. BST/London (5 a.m. EDT/3 a.m. MDT). Media may conduct interviews around the findings in advance of that date, but the information may not be published, broadcast, or posted online until after the release window. Journalists are permitted to show papers to independent specialists under embargo conditions, solely for the purpose of commenting on the work described

University researchers have shown that a transition to green wastewater-treatment approaches in the U.S. that leverages the potential of carbon-financing could save a staggering $15.6 billion and just under 30 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions ...

Specific nasal cells protect against COVID-19 in children

2024-04-15

Important differences in how the nasal cells of young and elderly people respond to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, could explain why children typically experience milder COVID-19 symptoms, finds a new study led by researchers at UCL and the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The study, published in Nature Microbiology, focused on the early effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the cells first targeted by the viruses, the human nasal epithelial cells (NECs).

These cells were donated from healthy participants from Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), University College London Hospital (UCLH) and the Royal ...

Tropical forests can't recover naturally without fruit eating birds

2024-04-15

New research from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich illustrates a critical barrier to natural regeneration of tropical forests. Their models – from ground-based data gathered in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - show that when wild tropical birds move freely across forest landscapes, they can increase the carbon storage of regenerating tropical forests by up to 38 percent.

Birds seed carbon potential

Fruit eating birds such as the Red-Legged Honeycreeper, Palm Tanager, or the Rufous-Bellied Thrush play a vital role in forest ecosystems by consuming, excreting, and ...

Newly sequenced genome reveals coffee’s prehistoric origin story — and its future under climate change

2024-04-15

BUFFALO, N.Y. — The key to growing coffee plants that can better resist climate change in the decades to come may lie in the ancient past.

Researchers co-led by the University at Buffalo have created what they say is the highest quality reference genome to date of the world’s most popular coffee species, Arabica, unearthing secrets about its lineage that span millennia and continents.

Their findings, published today in Nature Genetics, suggest that Coffea arabica developed more than 600,000 years ago in the forests of Ethiopia ...

Human muscle map reveals how we try to fight effects of ageing

2024-04-15

How muscle changes with ageing, and tries to fight its effects, is now better understood at the cellular and molecular level with the first comprehensive atlas of ageing muscles in humans.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and their collaborators at Sun Yat-sen University, China applied single-cell technologies and advanced imaging to analyse human skeletal muscle samples from 17 individuals across the adult lifespan. By comparing the results, they shed new light on the many complex processes underlying age-related muscle changes.

The atlas, published ...

Study shows key role of physical activity and body mass in lung function growth in childhood

2024-04-15

A new study led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a centre supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation, sheds light on the growth of lung function in children. The results show that increased levels of physical activity and a higher body mass index (BMI) play a key role in the recovery of early deficits. These findings, published in the journal Thorax, have important implications for clinical practice, research and public health policy, providing new insights into how to improve respiratory health from childhood to adulthood.

The study analysed data from the ...

Security vulnerability in browser interface allows computer access via graphics card

2024-04-15

Modern websites place ever greater demands on the computing power of computers. For this reason, web browsers have also had access to the computing capacities of the graphics card (Graphics Processing Unit or GPU) in addition to the CPU of a computer for a number of years. The scripting language JavaScript can utilise the resources of the GPU via programming interfaces such as WebGL and the new WebGPU standard. However, this harbours risks. Using a website with malicious JavaScript, researchers from the Institute of Applied Information Processing and Communications at Graz University of Technology (TU Graz) were able to spy on information about data, keystrokes and encryption ...

Physical activity reduces stress-related brain activity to lower cardiovascular disease risk

2024-04-15

Key Takeaways

Results from a new study indicate that physical activity may help protect against cardiovascular disease in part by reducing stress-related brain activity

This effect in the brain may help to explain why study participants with depression (a stress-related condition) experienced the greatest cardiovascular benefits from physical activity.

BOSTON – New research indicates that physical activity lowers cardiovascular disease risk in part by reducing stress-related signaling in the brain.

In the study, which was led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare ...

Inaugural International COSPAR Planetary Protection Week: Set to inspire global collaboration in London

2024-04-15

With an increasing number of space missions targeting various celestial bodies, including Mars, Europa, and the Moon, the importance of maintaining the integrity of these environments while protecting our own biosphere has never been greater. The ICPPW will serve as a platform for promoting international collaboration and knowledge exchange on best practice in planetary protection.

The event will feature a range of sessions, meetings, as well as panel discussions, covering key topics such as the current and ...