(Press-News.org) The health benefits of exercise are well known but new research shows that the body’s response to exercise is more complex and far-reaching than previously thought. In a study on rats, a team of scientists from across the United States has found that physical activity causes many cellular and molecular changes in all 19 of the organs they studied in the animals.

Exercise lowers the risk of many diseases, but scientists still don’t fully understand how exercise changes the body on a molecular level. Most studies have focused on a single organ, sex, or time point, and only include one or two data types.

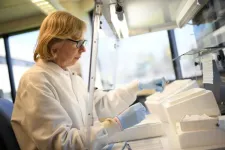

To take a more comprehensive look at the biology of exercise, scientists with the Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC) used an array of techniques in the lab to analyze molecular changes in rats as they were put through the paces of weeks of intense exercise. Their findings appear in Nature.

The team studied a range of tissues from the animals, such as the heart, brain, and lungs. They found that each of the organs they looked at changed with exercise, helping the body to regulate the immune system, respond to stress, and control pathways connected to inflammatory liver disease, heart disease, and tissue injury.

The data provide potential clues into many different human health conditions; for example, the researchers found a possible explanation for why the liver becomes less fatty during exercise, which could help in the development of new treatments for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

The team hopes that their findings could one day be used to tailor exercise to an individual’s health status or to develop treatments that mimic the effects of physical activity for people who are unable to exercise. They have already started studies on people to track the molecular effects of exercise.

Launched in 2016, MoTrPAC draws together scientists from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Stanford University, the National Institutes of Health, and other institutions to shed light on the biological processes that underlie the health benefits of exercise. The Broad project was originally conceived of by Steve Carr, senior director of Broad’s Proteomics Platform; Clary Clish, senior director of Broad’s Metabolomics Platform; Robert Gerszten, a senior associate member at the Broad and chief of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; and Christopher Newgard, a professor of nutrition at Duke University.

Co-first authors on the study include Pierre Jean-Beltran, a postdoctoral researcher in Carr’s group at Broad when the study began, as well as David Amar and Nicole Gay of Stanford. Courtney Dennis and Julian Avila, both researchers in Clish’s group, were also co-authors on the manuscript.

“It took a village of scientists with distinct scientific backgrounds to generate and integrate the massive amount of high quality data produced,” said Carr, a co-senior author of the study. “This is the first whole-organism map looking at the effects of training in multiple different organs. The resource produced will be enormously valuable, and has already produced many potentially novel biological insights for further exploration.”

The team has made all of the animal data available in an online public repository. Other scientists can use this site to download, for example, information about the proteins changing in abundance in the lungs of female rats after eight weeks of regular exercise on a treadmill, or the RNA response to exercise in all organs of male and female rats over time.

Whole-body analysis

Conducting such a large and detailed study required a lot of planning. “The amount of coordination that all of the labs involved in this study had to do was phenomenal,” said Clish.

In partnership with Sue Bodine at the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa, whose group collected tissue samples from animals after up to eight weeks of training, other members of the MoTrPAC team divided the samples up so that each lab — Carr’s team analyzing proteins, Clish’s studying metabolites, and others — would examine virtually identical samples.

“A lot of large-scale studies only focus on one or two data types,” said Natalie Clark, a computational scientist in Carr’s group. “But here we have a breadth of many different experiments on the same tissues, and that’s given us a global overview of how all of these different molecular layers contribute to exercise response.”

In all, the teams performed nearly 10,000 assays to make about 15 million measurements on blood and 18 solid tissues. They found that exercise impacted thousands of molecules, with the most extreme changes in the adrenal gland, which produces hormones that regulate many important processes such as immunity, metabolism, and blood pressure. The researchers uncovered sex differences in several organs, particularly related to the immune response over time. Most immune-signaling molecules unique to females showed changes in levels between one and two weeks of training, whereas those in males showed differences between four and eight weeks.

Some responses were consistent across sexes and organs. For example, the researchers found that heat-shock proteins, which are produced by cells in response to stress, were regulated in the same ways across different tissues. But other insights were tissue-specific. To their surprise, Carr’s team found an increase in acetylation of mitochondrial proteins involved in energy production, and in a phosphorylation signal that regulates energy storage, both in the liver that changed during exercise. These changes could help the liver become less fatty and less prone to disease with exercise, and could give researchers a target for future treatments of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

“Even though the liver is not directly involved in exercise, it still undergoes changes that could improve health. No one speculated that we’d see these acetylation and phosphorylation changes in the liver after exercise training,” said Jean-Beltran. “This highlights why we deploy all of these different molecular modalities — exercise is a very complex process, and this is just the tip of the iceberg.”

“Two or three generations of research associates matured on this consortium project and learned what it means to carefully design a study and process samples,” added Hasmik Keshishian, a senior group leader in Carr’s group and co-author of the study. “Now we are seeing the results of our work: biologically insightful findings that are yielding from the high quality data we and others have generated.That’s really fulfilling.”

Other MoTrPAC papers published today include deeper dives into the response of fat and mitochondria in different tissues to exercise. Additional MoTrPAC studies are underway to study the effects of exercise on young adult and older rats, and the short-term effects of 30-minute bouts of physical activity. The consortium has also begun human studies, and are recruiting about 1,500 individuals of diverse ages, sexes, ancestries, and activity levels for a clinical trial to study the effects of both endurance and resistance exercise in children and adults.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Paper cited:

MoTrPAC Study Group. Temporal dynamics of the multi-omic response to endurance exercise training. Nature. Online May 1, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06877-w.

About Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard was launched in 2004 to empower this generation of creative scientists to transform medicine. The Broad Institute seeks to describe the molecular components of life and their connections; discover the molecular basis of major human diseases; develop effective new approaches to diagnostics and therapeutics; and disseminate discoveries, tools, methods and data openly to the entire scientific community.

Founded by MIT, Harvard, Harvard-affiliated hospitals, and the visionary Los Angeles philanthropists Eli and Edythe L. Broad, the Broad Institute includes faculty, professional staff and students from throughout the MIT and Harvard biomedical research communities and beyond, with collaborations spanning over a hundred private and public institutions in more than 40 countries worldwide.

END

Scientists work out the effects of exercise at the cellular level

Prolonged physical activity in rats results in profound changes to RNA, proteins, and metabolites in nearly all tissues, providing clues to many human health conditions.

2024-05-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

CHOP researchers identify causal genetic variant linked to common childhood obesity

2024-05-01

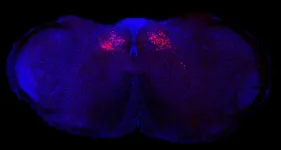

Philadelphia, May 1, 2024 – Researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have identified a causal genetic variant strongly associated with childhood obesity. The study provides new insight into the importance of the hypothalamus of the brain and its role in common childhood obesity and the target gene may serve as a druggable target for future therapeutic interventions. The findings were published today in the journal Cell Genomics.

Both environmental and genetic factors play critical roles in the increasing incidence of childhood ...

UVM scientists decode exercise's molecular impact

2024-05-01

BURLNGTON, Vt.—For the past eight years, researchers have been conducting a groundbreaking study supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund: The Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC). With nearly 2,600 volunteers, the study aims to examine the molecular effects of exercise on healthy adults and children, considering factors like age, race, and gender. The goal is to create comprehensive molecular maps of these changes and uncover why physical activity has significant health benefits.

“This ...

Differences in cardiovascular health at the intersection of race, ethnicity, and sexual identity

2024-05-01

About The Study: This cross-sectional study uses National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data to examine differences in cardiovascular health metrics at the intersection of race, ethnicity, and sexual identity.

Authors: Nicole Rosendale, M.D., of the University of California San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.9053)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...

Plant-based diets and disease progression in men with prostate cancer

2024-05-01

About The Study: Higher intake of plant foods after prostate cancer diagnosis was associated with lower risk of cancer progression, this study suggests.

Authors: Stacey A. Kenfield, Sc.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.9053)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

# # #

Embed this ...

Columbia scientists identify new brain circuit in mice that controls body’s inflammatory reactions

2024-05-01

NEW YORK, NY — The brain can direct the immune system to an unexpected degree, capable of detecting, ramping up and tamping down inflammation, shows a new study in mice from researchers at Columbia's Zuckerman Institute.

"The brain is the center of our thoughts, emotions, memories and feelings," said Hao Jin, PhD, a co-first author of the study published online today in Nature. "Thanks to great advances in circuit tracking and single-cell technology, we now know the brain does far more than that. It is monitoring the function of every system in the body."

Future ...

Nutrient research reveals pathway for treating brain disorders

2024-05-01

A University of Queensland researcher has found molecular doorways that could be used to help deliver drugs into the brain to treat neurological disorders.

Dr Rosemary Cater from UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience led a team which discovered that an essential nutrient called choline is transported into the brain by a protein called FLVCR2.

“Choline is a vitamin-like nutrient that is essential for many important functions in the body, particularly for brain development,” Dr Cater said.

“We need to consume 400-500 mg of choline ...

Nationwide, 6 stroke advocates selected to receive 2024 Stroke Hero Awards

2024-05-01

DALLAS, May 1, 2024 — Each year, approximately 800,000 people in the U.S. have a stroke.[1] Six local stroke heroes from across the country are being recognized by the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association, for their resiliency and dedication in the fight against stroke.

The American Stroke Association’s annual Stroke Hero Awards honors stroke survivors, health care professionals, advocates and caregivers. During May, American Stroke Month, the Association, ...

Sleep resets brain connections – but only for first few hours

2024-05-01

During sleep, the brain weakens the new connections between neurons that had been forged while awake – but only during the first half of a night’s sleep, according to a new study in fish by UCL scientists.

The researchers say their findings, published in Nature, provide insight into the role of sleep, but still leave an open question around what function the latter half of a night’s sleep serves.

The researchers say the study supports the Synaptic Homeostasis Hypothesis, a key theory on the purpose of sleep which proposes that sleeping acts as a reset for the brain.

Lead author Professor Jason Rihel (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology) said: “When we are awake, ...

Rock solid evidence: Angola geology reveals prehistoric split between South America and Africa

2024-05-01

DALLAS (SMU) – An SMU-led research team has found that ancient rocks and fossils from long-extinct marine reptiles in Angola clearly show a key part of Earth’s past – the splitting of South America and Africa and the subsequent formation of the South Atlantic Ocean.

With their easily visualized “jigsaw-puzzle fit,” it has long been known that the western coast of Africa and the eastern coast of South America once nestled together in the supercontinent Gondwana — which broke off from the larger landmass of Pangea.

The research team says the southern coast of Angola, where they dug up the samples, arguably provides the most complete ...

Life expectancy in two disadvantaged areas higher than expected

2024-05-01

Better than expected life expectancy in two disadvantaged areas in England is probably due to population change according to local residents and professionals.

In the UK, people from the most disadvantaged areas can expect to die nine years earlier compared with people from the least disadvantaged areas while people in the north of England have lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality and worse health and wellbeing compared with national averages.

The study, funded by the NIHR School for Public Health Research, was a collaboration between Lancaster University, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Surface treatment of wood may keep harmful bacteria at bay

Carsten Bönnemann, MD, joins St. Jude to expand research on pediatric catastrophic neurological disorders

Women use professional and social networks to push past the glass ceiling

Trial finds vitamin D supplements don’t reduce covid severity but could reduce long COVID risk

Personalized support program improves smoking cessation for cervical cancer survivors

Adverse childhood experiences and treatment-resistant depression

Psilocybin trends in states that decriminalized use

New data signals high demand in aesthetic surgery in southern, rural U.S. despite access issues

$3.4 million grant to improve weight-management programs

Higher burnout rates among physicians who treat sickle cell disease

Wetlands in Brazil’s Cerrado are carbon-storage powerhouses

Brain diseases: certain neurons are especially susceptible to ALS and FTD

Father’s tobacco use may raise children’s diabetes risk

Structured exercise programs may help combat “chemo brain” according to new study in JNCCN

The ‘croak’ conundrum: Parasites complicate love signals in frogs

Global trends in the integration of traditional and modern medicine: challenges and opportunities

Medicinal plants with anti-entamoeba histolytica activity: phytochemistry, efficacy, and clinical potential

What a releaf: Tomatoes, carrots and lettuce store pharmaceutical byproducts in their leaves

Evaluating the effects of hypnotics for insomnia in obstructive sleep apnea

A new reagent makes living brains transparent for deeper, non-invasive imaging

Smaller insects more likely to escape fish mouths

Failed experiment by Cambridge scientists leads to surprise drug development breakthrough

Salad packs a healthy punch to meet a growing Vitamin B12 need

Capsule technology opens new window into individual cells

We are not alone: Our Sun escaped together with stellar “twins” from galaxy center

Scientists find new way of measuring activity of cell editors that fuel cancer

Teens using AI meal plans could be eating too few calories — equivalent to skipping a meal

Inconsistent labeling and high doses found in delta-8 THC products: JSAD study

Bringing diabetes treatment into focus

Iowa-led research team names, describes new crocodile that hunted iconic Lucy’s species

[Press-News.org] Scientists work out the effects of exercise at the cellular levelProlonged physical activity in rats results in profound changes to RNA, proteins, and metabolites in nearly all tissues, providing clues to many human health conditions.