(Press-News.org) Barcelona, 2 May 2024 - Discovered in the 1970s, circadian clocks are essential for the regulation of biological time in most cells in the human body. These internal mechanisms adjust biological processes to a 24-hour cycle, allowing the synchronisation of cellular functions with daily variations in the environment. Circadian rhythms, which are coordinated by a central clock in the brain that communicates with clocks in different peripheral tissues, influence many functions, from our sleep patterns to our ability to metabolise food.

A team led by Dr. Salvador Aznar Benitah, an ICREA researcher at IRB Barcelona, and Dr. Pura Muñoz-Cánoves, an ICREA researcher in the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences at the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), has described how the synchronisation between the central clock and peripheral clocks in muscle and skin plays a key role in ensuring the correct function of these tissues, as well as preventing degenerative processes associated with ageing.

The results of this work have been published in two articles in high-impact journals. In this regard, the research on the synchronisation between the central and peripheral clocks appears in Science, while the work on the coordination between the central clock and skin peripheral clock has been released in Cell Stem Cell. Both studies reveal the common mechanisms that underscore the importance of this coordination to uphold the optimal functionality of muscle and skin.

The work also describes the remarkable degree of autonomy of the peripheral clocks, which can maintain 24-h cycles and manage approximately 15% of circadian functions in the absence of the central clock.

“It is fascinating to see how synchronisation between the brain and peripheral circadian clocks plays a critical role in skin and muscle health, while peripheral clocks alone are autonomous in carrying out the most basic tissue functions,” says Dr. Aznar Benitah, head of the Stem Cell and Cancer laboratory at IRB Barcelona.

“Our study reveals that minimal interaction between only two tissue clocks (one central and the other peripheral) is needed to maintain optimal functioning of tissues like muscles and skin and to avoid their deterioration and ageing. Now, the next step is to identify the signalling factors involved in this interaction, with potential therapeutic applications in mind,” explains Dr. Muñoz-Cánoves, a UPF Professor who is now a Principal Investigator at Altos Labs (San Diego, US).

Coordination with the muscle peripheral clock maintains muscle function and prevents premature ageing

The study published in Science on the communication between the brain and muscle confirmed that the coordination between the central and peripheral clocks is crucial for maintaining daily muscle function and preventing the premature ageing of this tissue. Restoration of the circadian rhythm reduces the loss of muscle mass and strength, thereby improving deteriorated motor functions in experimental mouse models.

The results of the study have also demonstrated that time-restricted feeding (TRF), which involves eating only in the active phase of the day, can partially replace the central clock and enhance the autonomy of the muscle clock. More relevant still is that this restoration of the circadian rhythm through TRF can mitigate muscle loss, the deterioration of metabolic and motor functions, and the loss of muscle strength in aged mice.

These findings have significant implications for the development of therapies for muscular ageing and the enhancement of physical performance in older age. Drs. Arun Kumar and Mireia Vaca Dempere, both from the UPF, are the first authors of this study, which has also received contributions from Drs. Eusebio Perdiguero and Antonio Serrano, previously at the UPF and now at Altos Labs.

The peripheral clock of the skin integrates and modulates brain signals

In the study published in Cell Stem Cell, the team has demonstrated that the skin circadian clock is pivotal in coordinating the daily physiology of this tissue. By integrating brain signals, and sometimes by modifying them, this coordination ensures the correct functioning of the skin.

A surprising discovery was that, in the absence of the peripheral clock, the central body clock maintains the circadian rhythm of the skin but it works in the opposite way as usual (that is to say, on an opposite schedule). For example, the researchers observed that DNA replication, if regulated only by the central clock, would occur during the daytime, when skin is exposed to ultraviolet light, which would increase the risk of accumulating mutations. This phenomenon highlights the importance of the peripheral clock, which not only receives signals from the central clock—which coordinates the rhythms of the entire organism—but also adapts these signals to the specific needs of the tissue in which they are (in the case of skin stem cells, DNA replication peaks after exposure to ultraviolet light during the day).

Dr. Thomas Mortimer, a postdoctoral fellow at IRB Barcelona, and Dr. Patrick-Simon Welz, from the Hospital del Mar Research Institute, have headed this project, together with Drs. Aznar Benitah and Muñoz-Cánoves.

The results of the two studies stem from international collaboration with researchers from the University of California and the University of Texas Health in San Antonio (both in the US), the University of Lübeck in Alemania, the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, the Humanitas University in Italy, and Altos Labs San Diego Institute of Science in the US. The project was supported by funding from the European Research Council, the EU H2020 programme, the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the Government of Catalonia, the Lilliane Bettencourt Foundation, "la Caixa" Foundation, the Marató de TV3 Foundation, the BBVA Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Related articles:

The epidermal circadian clock integrates and subverts brain signals to guarantee skin homeostasis

Thomas Mortimer*, Valentina M. Zinna, Muge Atalay, Carmelo Laudanna, Oleg Deryagin, Guillem Posas, Jacob G. Smith, Elisa García-Lara, Mireia Vaca-Dempere, Leonardo Vinícius Monteiro de Assis, Isabel Heyde, Kevin B. Koronowski, Paul Petrus, Carolina M. Greco, Stephen Forrow, Henrik Oster, Paolo Sassone-Corsi, Patrick-Simon Welz*, Pura Muñoz-Cánoves*, Salvador Aznar Benitah*

Cell Stem Cell (2024) DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2024.04.013

Brain-muscle communication prevents muscle aging by maintaining daily physiology

Arun Kumar*, Mireia Vaca-Dempere*, Thomas Mortimer, Oleg Deryagin, Jacob G. Smith, Paul Petrus, Kevin B. Koronowski, Carolina M. Greco, Jessica Segalés, Eva Andrés, Vera Lukesova, Valentina M. Zinna, Patrick-Simon Welz, Antonio L. Serrano‡, Eusebio Perdiguero‡, Paolo Sassone-Corsi, Salvador Aznar Benitah*, Pura Muñoz-Cánoves*

Science (2023) DOI: 10.1126/science.adj8533

END

Synchronization between the central circadian clock and the circadian clocks of tissues preserves their functioning and prevents ageing

2024-05-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Physicists arrange atoms in extremely close proximity

2024-05-02

Proximity is key for many quantum phenomena, as interactions between atoms are stronger when the particles are close. In many quantum simulators, scientists arrange atoms as close together as possible to explore exotic states of matter and build new quantum materials.

They typically do this by cooling the atoms to a stand-still, then using laser light to position the particles as close as 500 nanometers apart — a limit that is set by the wavelength of light. Now, MIT physicists have developed a technique that allows them to arrange atoms in much closer proximity, down to a mere 50 nanometers. For context, a red blood cell ...

Scientists track ‘doubling’ in origin of cancer cells

2024-05-02

Working with human breast and lung cells, Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists say they have charted a molecular pathway that can lure cells down a hazardous path of duplicating their genome too many times, a hallmark of cancer cells.

The findings, published May 3 in Science, reveal what goes wrong when a group of molecules and enzymes trigger and regulate what’s known as the “cell cycle,” the repetitive process of making new cells out of the cells’ genetic material.

The findings could be used to develop therapies that interrupt snags in the cell cycle, ...

Human activity is causing toxic thallium to enter the Baltic sea, according to new study

2024-05-02

Woods Hole, Mass. (May 2, 2024) -- Human activities account for a substantial amount - anywhere from 20% to more than 60% - of toxic thallium that has entered the Baltic Sea over the past 80 years, according to new research by scientists affiliated with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and other institutions.

Currently, the amount of thallium (element symbol TI), which is considered the most toxic metal for mammals, remains low in Baltic seawater. However, the research suggests that the amount of thallium could increase due to further anthropogenic, or human induced, activities, or due to natural or human re-oxygenation of the Baltic that could make the sea ...

NREL proof of concept shows path to easier recycling of solar modules

2024-05-02

The use of femtosecond lasers to form glass-to-glass welds for solar modules would make the panels easier to recycle, according to a proof-of-concept study conducted by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL).

The welds would eliminate the need for plastic polymer sheets that are now laminated into solar modules but make recycling more difficult. At the end of their useful lifespan, the modules made with the laser welds can be shattered. The glass and metal wires running through the solar cells can be easily recycled and the silicon ...

NREL invites robots to help make wind turbine blades

2024-05-02

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) have successfully leveraged robotic assistance in the manufacture of wind turbine blades, allowing for the elimination of difficult working conditions for humans and the potential to improve the consistency of the product.

Although robots have been used by the wind energy industry to paint and polish blades, automation has not been widely adopted. Research at the laboratory demonstrates the ability of a robot to trim, grind, and sand blades. Those necessary steps occur after the two sides of the blade are made using a mold ...

Scent sells – but the right picture titillates both eyes and nose, research finds

2024-05-02

Scented products with relevant images on their packaging and branding, such as flowers or fruit, are more attractive to potential customers and score better in produce evaluations, new research confirms.

And such images, the researchers conclude, are particularly effective if manufacturers and marketers choose pictures that are more likely to stimulate a stronger sense of the imagined smell – for example, cut rather than whole lemons. This, they say, suggests that as well as seducing our eyes, the images are stimulating our sense of smell.

The study, published online in the International Journal of Research in Marketing, could provide manufacturers and marketers ...

Low intensity light to fight the effects of chronic stress

2024-05-02

Some neurological disorders can be improved through photobiomodulation, a non-invasive technique based on the application of low-intensity light to stimulate altered functions in specific regions of the body. Now, a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders reveals how photobiomodulation applied to the brain-gut axis is effective in recovering some cognitive alterations and sequelae caused by chronic stress. The study opens up new perspectives for applying the technique in future therapies for the treatment of neurological diseases in patients.

The article, based on the study of laboratory animal models, ...

Wildfires in wet African forests have doubled in recent decades

2024-05-02

American Geophysical Union

Press Release 24-19

2 May 2024

For Immediate Release

This press release is available online at: https://news.agu.org/press-release/africa-forest-fires-doubled-drying

Wildfires in wet African forests have doubled in recent decades

Climate change and human activities like deforestation are causing more fires in central and west Africa’s wet, tropical forests, according to the first-ever comprehensive survey there. The fires have long been overlooked.

AGU press contact:

Rebecca Dzombak, news@agu.org (UTC-4 hours)

Contact information ...

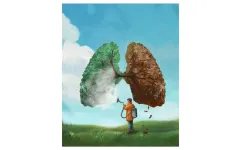

Dietary changes may treat pulmonary hypertension

2024-05-02

Blood vessels in the lungs aren’t like the others in the body. This difference becomes clear in pulmonary hypertension, in which only the lungs’ blood vessels stiffen progressively, leading to chronic lung disease, heart failure and death. The underlying reasons for this organ-specific vessel stiffening remained a mystery until University of Pittsburgh researcher Stephen Chan and colleagues made a surprising discovery about these blood vessel cells in patients with pulmonary hypertension—they’re hungry.

Chan, Vitalant Chair in Vascular Medicine and Professor of Medicine in the Division ...

UTA scientists test for quantum nature of gravity

2024-05-02

Einstein’s theory of general relativity explains that gravity is caused by a curvature of the directions of space and time. The most familiar manifestation of this is the Earth’s gravity, which keeps us on the ground and explains why balls fall to the floor and individuals have weight when stepping on a scale.

In the field of high-energy physics, on the other hand, scientists study tiny invisible objects that obey the laws of quantum mechanics—characterized by random fluctuations that create ...