(Press-News.org) Researchers at the University of Toronto have found naturally occurring compounds in the gut that can be harnessed to reduce inflammation and other symptoms of digestive issues. This can be achieved by binding the compounds to an important, but poorly understood, nuclear receptor.

The gut microbiome hosts bacteria that produce compounds as by-products of feeding on our digestive remnants. The compounds can bind to nuclear receptors, which help transcribe DNA to produce proteins and non-coding RNA segments.

By identifying which microbial by-products can be leveraged to regulate receptors, researchers hope to tap into their potential to treat disease.

“We conducted an unbiased screen of small molecules across the human gut microbiome,” said Jiabao Liu, first author on the study and research associate at U of T’s Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research. “We found that these molecules act similarly to artificial compounds that are currently being used to regulate the constitutive androstane receptor, otherwise known as CAR. This makes them viable candidates for drug development.”

The study was recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

CAR plays a critical role in regulating the breakdown, uptake and removal of foreign substances in the liver, including drugs. It is also involved in intestinal inflammation.

“One of the challenges with studying CAR is that there isn’t a useful compound that binds to both the human and mouse versions of the receptor – the latter being necessary for research and disease modeling prior to testing on people,” said Henry Krause, principal investigator on the study and professor of molecular genetics at the Donnelly Centre and the Temerty Faculty of Medicine. “Prior efforts focused on developing molecules with strong binding and activation capability. This has resulted in synthetic regulators that over-activate the receptor, which can lead to unintended outcomes. The natural compounds that we discovered don’t cause this issue.”

Two of the compounds found in the metabolite screen were diindolylmethane (DIM) and diindolylethane (DIE). While DIM has been previously identified from sampling the human gut, DIE has not. This study is the first time DIE has been detected in the human microbiome.

The two compounds regulated CAR in both the human and mouse liver. They were also found to match the effectiveness of an artificial human CAR regulator called CITCO.

A promising finding for future research on CAR regulation was that neither compound produced side effects, like liver enlargement, in mice. This means that DIM and DIE can be used to study CAR function and regulation in mice, where the findings can be applied to humans.

“This receptor plays a role in diabetes, fatty liver disease and small intestine ulcerative colitis,” said Liu. “We could potentially treat all of these issues with the two natural compounds we found that already exist in the human gut.”

This research was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, the American Cancer Society, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the New Frontiers in Research Fund.

END

U of T researchers discover compounds produced by gut bacteria that can treat inflammation

2024-05-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Aligned peptide ‘noodles’ could enable lab-grown biological tissues

2024-05-03

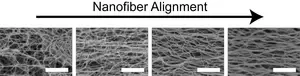

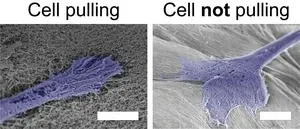

HOUSTON – (May 3, 2024) – A team of chemists and bioengineers at Rice University and the University of Houston have achieved a significant milestone in their work to create a biomaterial that can be used to grow biological tissues outside the human body. The development of a novel fabrication process to create aligned nanofiber hydrogels could offer new possibilities for tissue regeneration after injury and provide a way to test therapeutic drug candidates without the use of animals.

The research team, led by Jeffrey Hartgerink, professor of chemistry and bioengineering, has developed peptide-based hydrogels that mimic the aligned structure of muscle and ...

Law fails victims of financial abuse from their partner, research warns

2024-05-03

Victims of financial abuse from their partner in England and Wales are being failed by an “inadequate” legal response, new research warns.

Coerced debt causes considerable harm. People often live with the effects of being forced to give money or take out loans or credit cards long after the abusive relationship has ended.

Using the law to tackle it is more complex than other forms of abuse because to be free of the harmful effects of the abuse people’s contractual liability for the debt may need to be set aside. The law often favours lenders, who have little obligation to ensure that transactions are free from coercion.

New research recommends ...

Mental health first-aid training may enhance mental health support in prison settings

2024-05-03

According to Rutgers Health researchers, training correctional officers in Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) for adults, a 7.5-hour national education program from the National Council of Mental Wellbeing, may help provide them with the necessary skills to effectively identify signs and symptoms of mental distress and advocate for incarcerated individuals facing mental health crises.

Led by Pamela Valera, an assistant professor in the Department of Urban-Global Public Health at Rutgers School of Public Health, ...

Tweaking isotopes sheds light on promising approach to engineer semiconductors

2024-05-03

Research led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory has demonstrated that small changes in the isotopic content of thin semiconductor materials can influence their optical and electronic properties, possibly opening the way to new and advanced designs with the semiconductors.

Partly because of semiconductors, electronic devices and systems become more advanced and sophisticated every day. That’s why for decades researchers have studied ways to improve semiconductor compounds to influence how they carry electrical current. One approach is to use isotopes to ...

How E. coli get the power to cause urinary tract infections

2024-05-03

Through a quirk of anatomy, women are especially prone to urinary tract infections, with almost half dealing with one at some point in their lives.

Scientists have been trying to figure out for decades how bacteria gain a foothold in otherwise healthy people, examining everything from how the microbes move inside and stick to the inside of the bladder to how they deploy their toxins to produce uncomfortable and often painful symptoms.

Research published in PNAS examines how the bacteria Escherichia coli, or E. coli—responsible for most UTIs—is able to use host nutrients to reproduce at an extraordinarily rapid pace during ...

Quantifying U.S. health impacts from gas stoves

2024-05-03

Households with gas or propane stoves regularly breathe unhealthy levels of nitrogen dioxide, a study of air pollution in U.S. homes found.

“I didn’t expect to see pollutant concentrations breach health benchmarks in bedrooms within an hour of gas stove use, and stay there for hours after the stove is turned off,” said Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability Professor Rob Jackson, senior author of the May 3 study in Science Advances. Pollution from gas and propane stoves isn’t just an issue for cooks or people in the kitchen, ...

Physics confirms that the enemy of your enemy is, indeed, your friend

2024-05-03

Most people have heard the famous phrase “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

Now, Northwestern University researchers have used statistical physics to confirm the theory that underlies this famous axiom.

The study will be published on May 3 in the journal Science Advances.

In the 1940s, Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider introduced social balance theory, which explains how humans innately strive to find harmony in their social circles. According to the theory, four rules — an enemy of an enemy is a friend, a friend of a ...

Stony coral tissue loss disease is shifting the ecological balance of Caribbean reefs

2024-05-03

The outbreak of a deadly disease called stony coral tissue loss disease is destroying susceptible species of coral in the Caribbean while helping other, “weedier” organisms thrive — at least for now — according to a new study published today in Science Advances.

Researchers say the drastic change in the region’s population of corals is sure to disrupt the delicate balance of the ecosystem and threaten marine biodiversity and coastal economies.

“Some fast-growing organisms, like algae, ...

Newly discovered mechanism of T-cell control can interfere with cancer immunotherapies

2024-05-03

Activated T cells that carry a certain marker protein on their surface are controlled by natural killer (NK) cells, another cell type of the immune system. In this way, the body presumably curbs destructive immune reactions. Researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the University Medical Center Mannheim (UMM) now discovered that NK cells can impair the effect of cancer therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in this way. They could also be responsible for the rapid decline of therapeutic CAR-T cells. Interventions in this mechanism could ...

Wistar scientists discover new immunosuppressive mechanism in brain cancer

2024-05-03

PHILADELPHIA — (May 3, 2024) — The Wistar Institute assistant professor Filippo Veglia, Ph.D., and team, have discovered a key mechanism of how glioblastoma — a serious and often fatal brain cancer — suppresses the immune system so that the tumor can grow unimpeded by the body’s defenses. The lab’s discovery was published in the paper, “Glucose-driven histone lactylation promotes the immunosuppressive activity of monocyte-derived macrophages in glioblastoma,” in the journal Immunity.

“Our study shows that the cellular mechanisms of cancer’s self-preservation, when sufficiently understood, can be used against the disease very effectively,” ...