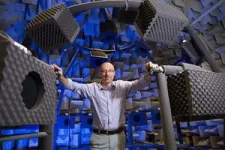

(Press-News.org) Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more adaptable and efficient hearing devices ranging from hearing aids to smartphones.

In the 1940s, an engineering model was developed to explain how humans can locate a sound source based on differences of just a few tens of millionths of a second in when the sound reaches each ear.

This model worked on the theory that we must have a set of specialised detectors whose only function was to determine where a sound was coming from, with location in space represented by a dedicated neuron.

Its assumptions have been guiding and influencing research – and the design of audio technologies – ever since.

But a new research paper published in Current Biology by Macquarie University Hearing researchers has finally revealed that the idea of a neural network dedicated to spatial hearing does not hold.

Lead author, Macquarie University Distinguished Professor of Hearing, David McAlpine, has spent the past 25 years proving that one animal after another was actually using a much sparser neural network, with neurons on both sides of the brain performing this function in addition to others.

Showing this in action in humans was more difficult.

Now through the combination of a specialised hearing test, advanced brain imaging, and comparisons with the brains of other mammals including rhesus monkeys, he and his team have shown for the first time that humans also use these simpler networks.

“We like to think that our brains must be far more advanced than other animals in every way, but that is just hubris,” Professor McAlpine says.

“We’ve been able to show that gerbils are like guinea pigs, guinea pigs are like rhesus monkeys, and rhesus monkeys are like humans in this regard.

“A sparse, energy efficient form of neural circuitry performs this function – our gerbil brain, if you like.”

The research team also proved that the same neural network separates speech from background sounds – a finding that is significant for the design of both hearing devices and the electronic assistants in our phones.

All types of machine hearing struggles with the challenge of hearing in noise, known as the ‘cocktail party problem’. It makes it difficult for people with hearing devices to pick out one voice in a crowded space, and for our smart devices to understand when we talk to them.

Professor McAlpine says his team’s latest findings suggest that rather than focusing on the large language models (LLMs) that are currently used, we should be taking a far simpler approach.

“LLMs are brilliant at predicting the next word in a sentence, but they’re trying to do too much,” he says.

“Being able to locate the source of a sound is the important thing here, and to do that, we don’t need a ‘deep mind’ language brain. Other animals can do it, and they don’t have language.

“When we are listening, our brains don’t keep tracking sound the whole time, which the large language processors are trying to do.

“Instead, we, and other animals, use our ‘shallow brain’ to pick out very small snippets of sound, including speech, and use these snippets to tag the location and maybe even the identity of the source.

“We don’t have to reconstruct a high-fidelity signal to do this, but instead understand how our brain represents that signal neurally, well before it reaches a language centre in the cortex.

“This shows us that a machine doesn’t have to be trained for language like a human brain to be able to listen effectively.

“We only need that gerbil brain.”

The next step for the team is to identify the minimum amount of information that can be conveyed in a sound but still get the maximum amount of spatial listening.

“The neural representation of an auditory spatial cue in the primate cortex”, by Dr Jaime Undurraga, Dr Robert Luke, Dr Lindsey Van Yper, Dr Jessica Monaghan, and Distinguished Professor David McAlpine, is published in the May edition of Current Biology: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.05.034

END

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

2024-05-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

It flickers, then it tips – study identifies early warning signals for the end of the African humid period

2024-05-07

The transition from the African Humid Period (AHP) to dry conditions in North Africa is the clearest example of climate tipping points in recent geological history. They occur when small perturbations trigger a large, non-linear response in the system and shift the climate to a different future state, usually with dramatic consequences for the biosphere. That was also the case in North Africa, where the grasslands, forests, and lakes favored by humans disappeared, causing them to retreat to areas like the mountains, oases, and the Nile Delta. This ...

Aquatic weed among ‘world’s worst’ expands in Northeastern US

2024-05-07

WESTMINSTER, Colorado – 7 May 2024 – An article in the latest issue of Invasive Plant Science and Management provides new insights on a northern hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) subspecies (lithuanica) and its establishment outside the Connecticut River. Considered among the “world’s worst” aquatic weeds, northern hydrilla hinders recreational activities by forming dense canopies. If unchecked, it has the potential to displace native species and host a bacterium that produces ...

Emergency department packed to the gills? Someday, AI may help

2024-05-07

UCSF-led study finds artificial intelligence is as good as a physician at prioritizing which patients need to be seen first.

Emergency departments nationwide are overcrowded and overtaxed, but a new study suggests artificial intelligence (AI) could one day help prioritize which patients need treatment most urgently.

Using anonymized records of 251,000 adult emergency department (ED) visits, researchers at UC San Francisco evaluated how well an AI model was able to extract symptoms from patients’ ...

Asthma education is key to reducing deaths worldwide, say respiratory health associations

2024-05-07

NEW YORK, NY - May 7, 2024 – On World Asthma Day 2024 the message is clear: "Asthma Education Empowers." The Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS), of which the American Thoracic Society is a founding member, stresses the crucial role of education in empowering people with asthma to manage their condition effectively and to know when to seek medical assistance.

FIRS also urges health care professionals to enhance their awareness of the preventable morbidity and mortality from asthma and of the published evidence on effective asthma management, so they are equipped to provide reliable information and optimal treatment for their patients.

Asthma ...

60% of women with disabilities view cannabis as a ‘harmless’ drug

2024-05-07

A growing number of states and territories in the United States have legalized medical and recreational cannabis use. As such, recreational cannabis has been associated with a lower perception of risk of harm in the general U.S. population.

However, in women of childbearing age, evidence has shown that cannabis use may increase the risk of adverse reproductive and perinatal health outcomes. Furthermore, research on the perception of risk from using cannabis among vulnerable populations such as those with disabilities is lacking.

Using data from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, researchers from Florida ...

Years after his death, late scientist's work could yield new cancer treatments

2024-05-07

Some of the final work of a late University of Virginia School of Medicine scientist has opened the door for life-saving new treatments for solid cancer tumors, including breast cancer, lung cancer and melanoma.

Prior to his sudden death in 2016, John Herr, PhD, had been collaborating with UVA Cancer Center’s Craig L. Slingluff Jr., MD, to investigate the possibility that a discovery from Herr’s lab could help treat cancer.

Eight years of research has borne that idea out: Herr’s research into the SAS1B protein could lead to “broad and profound” new treatments ...

SwRI evaluates reliability of pressure relief valves for liquid natural gas tanks in train derailment scenarios

2024-05-07

SAN ANTONIO — May 7, 2024 —Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) has helped determine the viability of pressure relief valves for liquid natural gas tanks in the event of a train derailment for the Federal Rail Administration (FRA). The report from the FRA shows that a study conducted by SwRI demonstrates that the pressure relief valves work as designed to prevent overpressurization and explosion if a derailment occurs.

“The pressure relief valves on tanks that transport liquid ...

Study: You’re breathing potential carcinogens inside your car

2024-05-07

The air inside all personal vehicles is polluted with harmful flame retardants—including those known or suspected to cause cancer—according to a new peer-reviewed study published in Environmental Science & Technology. Car manufacturers add these chemicals to seat foam and other materials to meet an outdated federal flammability standard with no proven fire-safety benefit.

“Our research found that interior materials release harmful chemicals into the cabin air of our cars,” said lead author Rebecca ...

Using AI to predict GPA from college application essays

2024-05-07

Jonah Berger and Olivier Toubia used natural language processing to understand what drives academic success. The authors analyzed over 20,000 college application essays from a large public university that attracts students from a range of racial, cultural, and economic backgrounds and found that the semantic volume of the writing, or how much ground an application essay covered predicted college performance, as measured by grade point average. Essays that covered more semantic ground predicted higher grades. Similarly, essays with smaller conceptual jumps between successive parts of ...

Few tenure-track jobs for engineering PhDs

2024-05-07

A study finds that most engineering PhD graduates will never secure a tenure-track faculty position. Over the past 50 years, the number of full-time faculty positions in US universities has steadily declined while production of science and engineering PhD graduates has nearly doubled. Siddhartha Roy and colleagues analyzed data on PhD graduates and tenure-track and tenured faculty members across all engineering disciplines from 2006–2021. The average annual likelihood of securing a tenure-track faculty position in engineering during this 16-year period was 12.4%. The likelihood of securing a tenure-track faculty position was 18.5% in ...