(Press-News.org) The researchers conducted a study over four days, including overnight stays, with 18 subjects at :envihab, the DLR medical research centre in Cologne. At a simulated altitude of 2500 meters above sea level, the influence of hypoxia (oxygen deficiency) on various hemodynamic and metabolic parameters was investigated. The central venous pressure via a catheter and the blood flow in the lungs using real-time magnetic resonance imaging were evaluated. The results showed that neither the pulmonarypressure nor the blood flow changed significantly. All patients able to tolerate a longer stay at altitude of 24 to 30 hours without complications.

Oxygenation levels stable even during sleep

Additionally the research team analyzed the oxygen saturation values during sleep. ‘The breathing pattern during sleep at altitude can be fundamentally different,’ explains Dr Nicole Müller, head of the study and senior physician at the Department of Paediatric Cardiology at the UKB. ‘Even in healthy people, breathing is altered with short pauses. It was therefore exciting for us to observe if and how the high altitude exposure affects patients with Fontan physiology during sleep.’ Fortunately, the analyses showed that oxygen saturation is also sufficient during sleep and that the decrease is comparable to that of healthy people.

‘These are great results,’ says Dr Müller. ‘I think that this offers many patients with Fontan circulation new perspectives. Previously, there was only data on how short-term hypoxia affects their cardiovascular system - but data on prolonged hypoxia, including overnight stays, has been lacking until now. Many of those affected have therefore never dared to spend a longer period at ambient hypoxia, such as an overnight stay in the mountains or a long-haul flight to Australia. Our study now shows that, under certain conditions, there is no health risk.’ The findings may provide guidance for physicians caring for individuals with Fontan circulation considering long-duration airplane travel or shorter stays at high altitude.

‘DLR's :envihab at the Cologne site offers unique opportunities for patient-oriented research,’ says Prof Dr Jens Tank, Head of the Cardiovascular Aerospace Medicine Department at DLR. ‘The invasive pressure measurement in the Fontan circulation and the examination with real-time MRI cannot be realized at altitude under real conditions. In the :envihab, we were able to examine the Fontan patients over several days and nights under very comfortable conditions and safely expose them to an oxygen-reduced atmosphere. We very much hope that we will be able to conduct further exciting studies together in the future.’

‘This is a great development for medicine and contributes to better quality of life for all patients with congenital heart defects,’ adds Sylvia Paul, CEO of the Children's Heart Foundation. ‘We are delighted to be able to support the joint study by the UKB, the DLR and the German Sport University Cologne and thus contribute to giving Fontan patients a better quality of life.’

Funding: The study is supported by the KinderHerz Foundation, which is funded by donations. For further information see here: www.stiftung-kinderherz.de/was-wir-tun/unsere-foerderprojekte/hoehenanpassung-bei-fontan-patienten-bonn

END

Simulated High-altitude exposure for 24-hours is well tolerated by adolescents and adults with single-ventricle physiology after Fontan-palliation

Joint HYPOFON study by University Hospital Bonn, the Institute of Aerospace Medicine (DLR, Cologne) and the German Sport University Cologne shows that the circulation remains stable

2024-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists find ancient, endangered lamprey fish in Queensland, 1400 km north of its previous known range

2024-05-08

The Australian brook lamprey (Mordacia praecox) is part of a group of primitive jawless fish. It’s up to 15 cm long, with rows of sharp teeth. Surprisingly, it doesn’t use these teeth to suck blood like most lamprey species – it’s non-parasitic.

As larvae, the Australian brook lamprey lives buried in the bottom of streams for around three years, filter-feeding. Its adult phase is about one year long, in which it doesn’t feed at all. Prior to this study – funded in part by the Australian Government through the National Environmental Science Program’s (NESP) Resilient Landscapes Hub – the species was widely believed to only live in a few streams ...

New $3.7m climate crop lab will create food for ‘tomorrow’s atmosphere today’

2024-05-08

A unique $3.7m plant lab will put researchers on the frontline in the fight against climate change and create crops for “tomorrow’s atmosphere today”.

The new flagship facility at the University of Essex will allow scientists to adapt plants for a hotter drier planet as food security is increasingly threatened.

It boasts a cutting-edge commercially standard vertical farm, an indoor field that replicates real environments anywhere in the globe, and suites that imitate a warming world – with researchers able to raise CO2 concentration and temperature levels at will.

Computer ...

New air-breathing spacecraft to provide better Earth observation and quicker communications

2024-05-08

Scientists at the University of Surrey are developing a new way to power low-orbit spacecraft using – literally – thin air.

Surrey Space Centre aims to enable extremely low-altitude spacecraft orbits in the upper atmosphere, thanks to funding from the UK Space Agency.

This new spacecraft concept could offer new capabilities in Earth observation, climate monitoring and satellite communications.

Dr Andrea Lucca Fabris, principal investigator from Surrey Space Centre and an electric propulsion specialist, said:

“There are benefits to flying in very low altitude orbits, like being able to operate Earth observation at much ...

Exploring the asteroid apophis with small satellites

2024-05-08

The author of a disaster novel couldn't have dreamed it up any better: On a Friday, the thirteenth of all days, the potentially dangerous asteroid (99942) Apophis will come extremely close to humanity. On 13 April 2029, there will only be around 30,000 kilometres between the cosmic rock and Earth. It will then be possible to see Apophis with the naked eye as a point of light in the evening sky, even from Würzburg.

What makes the asteroid so dangerous: its average diameter is an impressive 340 metres. If it were to hit the Earth, the ...

Research warns of hazardous health risks from flavored vapes

2024-05-08

Research warns of hazardous health risks from flavoured vapes

Research predicts the potential formation of 127 acutely toxic chemicals in flavoured vapes

Findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive regulation of vaping products

Wednesday, 8 May 2024: New research has uncovered the potentially harmful substances that are produced when e-liquids in vaping devices are heated for inhalation. The study, published in Scientific Reports, highlights the urgent need for public health policies concerning flavoured vapes.

The research team at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin, used artificial ...

FAU researchers receive $1M in FDOH grants to fight Alzheimer’s disease

2024-05-08

Three Florida Atlantic University researchers at the forefront of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research have each received a $350,000 grant from the Florida Department of Health’s “Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program.”

The Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program was established to improve the health of Floridians by stimulating research into the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, care management and cure of AD.

Florida has the second highest incidence of AD in the nation with 580,000 people ages 65 and ...

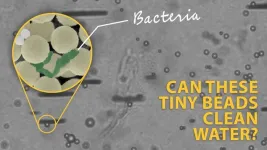

Swarms of miniature robots clean up microplastics and microbes, simultaneously (video)

2024-05-08

When old food packaging, discarded children’s toys and other mismanaged plastic waste break down into microplastics, they become even harder to clean up from oceans and waterways. These tiny bits of plastic also attract bacteria, including those that cause disease. In a study in ACS Nano, researchers describe swarms of microscale robots (microrobots) that captured bits of plastic and bacteria from water. Afterward, the bots were decontaminated and reused. Watch a video of them swarming.

The size ...

Where wildlife is welcome

2024-05-08

How do city residents feel about animals in their immediate surroundings? A recent study by the Technical University of Munich (TUM), the University of Jena and the Vienna University of Technology shows how different the acceptance of various wild animals in urban areas is. Important factors are the places where the animals are found and their level of popularity - squirrels and ladybugs come out on top here. The results have important implications for urban planning and nature conservation.

The relationship between city inhabitants and urban animals is complex, ...

THC lingers in breastmilk with no clear peak point

2024-05-08

PULLMAN, Wash. – When breastfeeding mothers in a recent study used cannabis, its psychoactive component THC showed up in the milk they produced. The Washington State University-led research also found that, unlike alcohol, when THC was detected in milk there was no consistent time when its concentration peaked and started to decline.

Importantly, the researchers discovered that the amount of THC they detected in milk was low – they estimated that infants received an average of 0.07 mg of THC per day. For comparison, a common low-dose edible contains 2 mg of THC. The research team stressed that it is unknown whether this amount has any impact ...

An AI leap into chemical synthesis

2024-05-08

Chemistry, with its intricate processes and vast potential for innovation, has always been a challenge for automation. Traditional computational tools, despite their advanced capabilities, often remain underutilized due to their complexity and the specialized knowledge required to operate them.

Now, researchers with the group of Philippe Schwaller at EPFL, have developed ChemCrow, an AI that integrates 18 expertly designed tools, enabling it to navigate and perform tasks within chemical research with unprecedented efficiency. “You might wonder why a crow?” asks Schwaller. “Because ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The RESIL-Card tool launches across Europe to strengthen cardiovascular care preparedness against crises

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

[Press-News.org] Simulated High-altitude exposure for 24-hours is well tolerated by adolescents and adults with single-ventricle physiology after Fontan-palliationJoint HYPOFON study by University Hospital Bonn, the Institute of Aerospace Medicine (DLR, Cologne) and the German Sport University Cologne shows that the circulation remains stable