(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — By converting their data into sounds, scientists discovered how hydrogen bonds contribute to the lightning-fast gyrations that transform a string of amino acids into a functional, folded protein. Their report, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offers an unprecedented view of the sequence of hydrogen-bonding events that occur when a protein morphs from an unfolded to a folded state.

See video: Protein Sonification

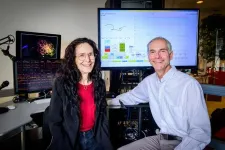

“A protein must fold properly to become an enzyme or signaling molecule or whatever its function may be — all the many things that proteins do in our bodies,” said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign chemistry professor Martin Gruebele, who led the new research with composer and software developer Carla Scaletti.

Misfolded proteins contribute to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, cystic fibrosis and other disorders. To better understand how this process goes awry, scientists must first determine how a string of amino acids shape-shifts into its final form in the watery environment of the cell. The actual transformations occur very fast, “somewhere between 70 nanoseconds and two microseconds,” Gruebele said.

Hydrogen bonds are relatively weak attractions that align atoms located on different amino acids in the protein. A folding protein will form a series of hydrogen bonds internally and with the water molecules that surround it. In the process, the protein wiggles into countless potential intermediate conformations, sometimes hitting a dead-end and backtracking until it stumbles onto a different path.

See video: Protein Sonification: Hairpin in a trap

The researchers wanted to map the time sequence of hydrogen bonds that occur as the protein folds. But their visualizations could not capture these complex events.

“There are literally tens of thousands of these interactions with water molecules during the short passage between the unfolded and folded state,” Gruebele said.

So the researchers turned to data sonification, a method for converting their molecular data into sounds so that they could “hear” the hydrogen bonds forming. To accomplish this, Scaletti wrote a software program that assigned each hydrogen bond a unique pitch. Molecular simulations generated the essential data, showing where and when two atoms were in the right position in space — and close enough to one another — to hydrogen bond. If the correct conditions for bonding occurred, the software program played a pitch corresponding to that bond. Altogether, the program tracked hundreds of thousands of individual hydrogen-bonding events in sequence.

See video: Using sound to explore hydrogen bond dynamics during protein folding

Numerous studies suggest that audio is processed roughly twice as fast as visual data in the human brain, and humans are better able to detect and remember subtle differences in a sequence of sounds than if the same sequence is represented visually, Scaletti said.

“In our auditory system, we’re really very attuned to small differences in frequency,” she said. “We use frequencies and combinations of frequencies to understand speech, for example.”

A protein spends most of its time in the folded state, so the researchers also came up with a “rarity” function to identify when the rare, fleeting moments of folding or unfolding took place.

The resulting sounds gave them insight into the process, revealing how some hydrogen bonds seem to speed up folding while others appear to slow it. They characterized these transitions, calling the fastest “highway,” the slowest “meander,” and the intermediate ones “ambiguous.”

Including the water molecules in the simulations and hydrogen-bonding analysis was essential to understanding the process, Gruebele said.

“Half of the energy from a protein-folding reaction comes from the water and not from the protein,” he said. “We really learned by doing sonification how water molecules settle into the right place on the protein and how they help the protein conformation change so that it finally becomes folded.”

While hydrogen bonds are not the only factor contributing to protein folding, these bonds often stabilize a transition from one folded state to another, Gruebele said. Other hydrogen bonds may temporarily impede proper folding. For example, a protein may get hung up in a repeating loop that involves one or more hydrogen bonds forming, breaking and forming again — until the protein eventually escapes from this cul de sac to continue its journey to its most stable folded state.

“Unlike the visualization, which looks like a total random mess, you actually hear patterns when you listen to this,” Gruebele said. “This is the stuff that was impossible to visualize but it’s easy to hear.”

The National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health and Symbolic Sound Corporation supported this research.

Gruebele also is a professor in the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology and an affiliate of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at the U. of I.

Editor’s note:

To reach Martin Gruebele, email mgruebel@illinois.edu.

To reach Carla Scaletti, email carla@symbolicsound.com.

The paper “Hydrogen bonding heterogeneity correlates with protein folding transition state passage time as revealed by data sonification” is available online or from pnasnews@nas.edu.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2319094121

END

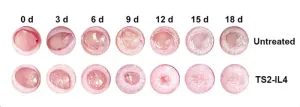

New York, NY [May 20, 2024]—Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have designed a regenerative medicine therapy to speed up diabetic wound repair. Using tiny fat particles loaded with genetic instructions to calm down inflammation, the treatment was shown to target problem-causing cells and reduce swelling and harmful molecules in mouse models of damaged skin.

Details on their findings were published in the May 20 online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Diabetic wounds, often resistant to conventional treatments, ...

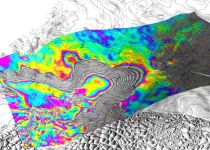

Irvine, Calif., May 20, 2024 — A team of glaciologists led by researchers at the University of California, Irvine used high-resolution satellite radar data to find evidence of the intrusion of warm, high-pressure seawater many kilometers beneath the grounded ice of West Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier.

In a study published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the UC Irvine-led team said that widespread contact between ocean water and the glacier – a process that is replicated throughout Antarctica and in Greenland – causes “vigorous melting” and may require a reassessment of ...

EMBARGOED UNTIL 15:00 EDT MONDAY, MAY 20, 2024

For the first time, there is visible evidence showing that warm seawater is pumping underneath Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier—ominously nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier.

An international team of scientists—including a researcher from the University of Waterloo—observed it using satellite imagery and warns that it could accelerate catastrophic sea level rise in 10 to 20 years.

The intrusion of seawater causes the ice to continuously lift off the land and settle back down again. Ice melts intensely when it first touches seawater, ...

Deposits of designated critical minerals needed to transition the world’s energy systems away from fossil fuels may, ironically enough, be co-located with coal deposits that have been mined to produce the fossil fuel most implicated in climate change.

Now, research led by the University of Utah has documented elevated concentrations of a key subset of critical minerals, known as rare earth elements, or REEs, in active mines rimming the Uinta coal belt of Colorado and Utah.

These findings open the possibility that these mines could see a secondary resource stream in the form of metals used in renewable energy and numerous other high-tech ...

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE: MONDAY, MAY 20, 2024, 3:00 PM ET

Key points:

Replacing an average diesel school bus from 2017 with an electric one may result in $84,200 in health and climate benefits—including fewer greenhouse gas emissions and reduced rates of mortality and childhood asthma—per individual bus.

Those benefits may increase to $247,600 per individual electric school bus replacing a diesel bus from 2005 or earlier in a large metropolitan area.

While the benefits of replacing diesel vehicles with electric ones are well known, this is the first study to specifically quantify the health and climate benefits of replacing diesel school buses with electric ...

Endoscopes are instruments that are used to look inside the body

Even with new developments cleaning them sufficiently has been a challenge

The University has entered a knowledge transfer partnership (KTP) with PFE Medical to improve the process by removing bacterial biofilm inside them.

Aston University experts are teaming up with a medical products company to improve the cleaning of endoscopes.

Endoscopes are long, thin instruments with a light and camera at one end that are used to look inside the body.

Cleaning them sufficiently has been a challenge and even with new developments they can ...

LA JOLLA, CA — The brain is often referred to as a “black box”—one that’s difficult to peer inside and determine what’s happening at any given moment. This is part of the reason why it’s difficult to understand the complex interplay of molecules, cells and genes that underly neurological disorders. But a new CRISPR screen method developed at Scripps Research has the potential to uncover new therapeutic targets and treatments for these conditions.

The method, outlined in a study published in Cell on May 20, 2024, provides a way to rapidly examine the brain cell types ...

Image

Artificial neural networks may soon be able to process time-dependent information, such as audio and video data, more efficiently. The first memristor with a 'relaxation time' that can be tuned is reported today in Nature Electronics, in a study led by the University of Michigan.

Memristors, electrical components that store information in their electrical resistance, could reduce AI's energy needs by about a factor of 90 compared to today's graphical processing units. Already, AI is projected to account for about half a percent of the world's total electricity ...

EMBARGOED UNTIL: 10:15 a.m. PT, Monday, May 20, 2024

PARC MODEL OF CARE ASSOCIATED WITH FEWER DEATHS AMONG VETERANS POST-ICU

Session: B18 – Bridging Gaps to Improve Long-Term Outcomes

The Post-Acute Recovery Center: A Telehealth Care Model to Improve Patient-Centered Outcomes for High-Risk Survivors of Critical Illness

Date and Time: Monday, May 20, 2024, 10:15 a.m. PT

Location: San Diego Convention Center, Room 32A-B (Upper Level)

ATS 2024, San Diego – Research presented at the ATS 2024 International Conference demonstrates that veterans who received ...

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Today, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced $6 million in funding for 12 awards across eight efforts to advance research in isotope enrichment, targetry, and separations. This funding is part of a key federal program that produces critical isotopes otherwise unavailable or in short supply in the U.S.

Isotopes, or variations of the same elements that have the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons, have unique properties that make them powerful in medical diagnostic and treatment applications. They are also essential for applications in quantum information science, nuclear power, national security, and more.

“These ...