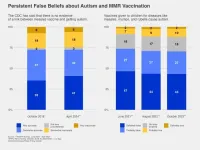

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has said there is no evidence linking the measles vaccine and getting autism. But 24% of U.S. adults do not accept that – they say that statement is somewhat or very inaccurate – and another 3% are not sure, according to the survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania. About three-quarters of those surveyed say that statement is somewhat or very accurate.

The findings are consistent with those in an APPC survey administered by NORC in October 2018, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. The two surveys indicate that a sizable and consistent number of Americans either believe the false connection or do not know what is correct. The false link was asserted by Andrew Wakefield in a 1998 Lancet paper that was subsequently retracted.

“The persistent false belief that the MMR vaccine causes autism continues to be problematic, especially in light of the recent increase in measles cases,” said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center. “Our studies on vaccination consistently show that the belief that the MMR vaccine causes autism is associated not simply with reluctance to take the measles vaccine but with vaccine hesitancy in general.”

The new survey findings are also consistent with APPC surveys in 2021-2023 which did not mention the CDC’s guidance. In these surveys, 9% to 12% thought it was probably or definitely true that vaccines given to children for diseases like measles, mumps, and rubella cause autism, while 17% to 18% were not sure whether that is true or false.

In the latest survey, conducted from April 18-24, 2024, the Annenberg Public Policy Center questioned over 1,500 empaneled U.S. adults about their knowledge of how one can contract measles, its symptoms, and whether medical professionals recommend that pregnant people take the measles vaccine if they have not already done so. See the survey topline.

The growth in measles cases The CDC reports that measles activity is increasing globally as well as in the United States. In 2024, as of May 30 there have been 146 U.S. measles cases in 21 jurisdictions, including 11 outbreaks of three or more related cases. From January 1, 2020, through March 28, 2024, the CDC was notified of 338 confirmed cases, of which nearly a third (97, or 29%) occurred just during the first quarter of 2024, which represents a 17-fold increase over the mean number of cases reported in the first quarters of 2020-2023. The median patient age was 3 years old. The vast majority of cases occurred in patients who were either unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown.

The percentage of kindergartners with MMR vaccine coverage against measles dropped in the United States during the pandemic, according to the CDC. “Measles Outbreaks Grow Amid Declining Vaccination Rates,” noted a JAMA Network headline in November 2023.

Measles knowledge How Measles Spread A majority of survey respondents know how measles can and cannot be spread. Nearly 6 in 10 correctly say that measles can be spread through coughing and sneezing (59%) and by touching a contaminated surface followed by touching one’s nose, mouth, or eyes (59%). Measles cannot be spread through unprotected sexual contact with an infected person, but over a fifth of those surveyed (22%) think this is a way to catch the virus.

Measles Incubation Period Very few of those surveyed know how long a person infected with measles can spread the virus before developing the signature measles rash. Just over 1 in 10 (12%) correctly estimate that a person can spread the infection for four days before developing a rash, while 12% estimate that the period is one week. The majority of panelists (55%) report not being sure.

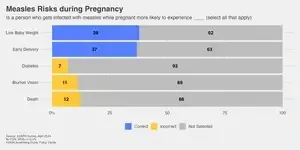

Measles complications for pregnant people The survey asked respondents to select whether a series of possible complications were associated with having measles while pregnant. Less than 4 in 10 people correctly (in blue below) identified two complications associated with contracting measles while pregnant – delivering a low-birth-weight baby (38%) and early delivery (37%). A fairly small number of people incorrectly (in yellow below) indicate that diabetes (7%), blurred vision (11%), and death (12%) are more likely to occur if you have measles while pregnant. They are not.

Measles vaccination (MMR) while pregnant Most people (57%) are not sure whether pregnant individuals should get vaccinated against measles if they have not already been vaccinated against it. Almost one-third (32%) incorrectly think that medical professionals recommend that pregnant people take the vaccine. Only 12% know that medical professionals do not recommend this vaccine for pregnant individuals. This is because the measles vaccine uses a live, weakened (i.e., attenuated) form of the virus. The CDC notes: “Even though MMR is a safe and effective vaccine, there is a theoretical risk to the baby. This is because it is a live vaccine, meaning it contains a weakened version of the living viruses.”

The CDC recommends the MMR vaccine be given a month or more before someone becomes pregnant, if that person was not vaccinated against measles, mumps, and rubella as a child.

APPC’s ASAPH survey The survey data come from the 19th wave of a nationally representative panel of 1,522 U.S. adults, first empaneled in April 2021, conducted for the Annenberg Public Policy Center by SSRS, an independent market research company. This wave of the Annenberg Science and Public Health Knowledge (ASAPH) survey was fielded April 18-24, 2024, and has a margin of sampling error (MOE) of ± 3.5 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. All figures are rounded to the nearest whole number and may not add to 100%. Combined subcategories may not add to totals in the topline and text due to rounding.

Download the topline and methodology statement.

The policy center has been tracking the American public’s knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors regarding vaccination, Covid-19, flu, maternal health, climate change, and other consequential health issues through this survey panel for over three years. In addition to Jamieson, the APPC team behind this survey includes Shawn Patterson, who analyzed the data; Patrick E. Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Health and Risk Communication Institute, who developed the questions; and Ken Winneg, managing director of survey research, who supervised the fielding of the survey.

The 2018 survey data comes from the first wave of the Annenberg Public Policy Center's Resistance to Vaccines Longitudinal Survey (RVLS), a panel of 3,005 U.S. adults, conducted by NORC, an independent research company. This wave was fielded between September 21, 2018, and October 6, 2018, and has a margin of sampling error of ± 2.6 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

###

The Annenberg Public Policy Center was established in 1993 to educate the public and policy makers about communication’s role in advancing public understanding of political, science, and health issues at the local, state, and federal levels.

END