(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA—What happens when measles virus meets a human cell? The viral machinery unfolds in just the right way to reveal key pieces that let it fuse itself into the host cell membrane.

Once the fusion process is complete, the host cell is a goner. It belongs to the virus now.

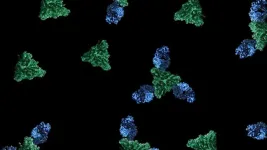

Scientists in the La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) Center for Vaccine Innovation are working to develop new measles vaccines and therapeutics that stop this fusion process. The researchers recently harnessed an imaging technique called cryo-electron microscopy to show—in unprecedented detail—how a powerful antibody can neutralize the virus before it completes the fusion process.

"What’s exciting about this study is that we’ve captured snapshots of the fusion process in action," explains LJI Professor, President and CEO Erica Ollmann Saphire, Ph.D., who co-led the Science study with Matteo Porotto, Ph.D., Professor of Viral Molecular Pathogenesis (in Pediatrics) at Columbia University. “The series of images is like a flip book where we see snapshots along the way of the fusion protein unfolding, but then we see the antibody locking it together before it can complete the last stage in the fusion process. We think other antibodies against other viruses will do the same thing but have not been imaged like this before.”

Indeed this work may prove important beyond measles. Measles virus is just one member of the larger paramyxovirus family, which also includes the deadly Nipah virus. Nipah virus is known for being less contagious but causing a much higher mortality rate than measles.

"What we learn about the fusion process can be medically relevant for Nipah, parainfluenza viruses, and Hendra virus," says study first author and LJI Postdoctoral Researcher Dawid Zyla, Ph.D. "These are all viruses with pandemic potential."

The urgent need for measles treatments

Measles is a highly contagious, airborne disease that tends to strike children the hardest. Despite extensive vaccine efforts, the virus remains a major health threat. According to the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, measles caused around 136,000 deaths globally in 2022, with recent outbreaks in over a dozen U.S. states. The victims were mostly children under age five who were unvaccinated or undervaccinated.

"Measles causes more childhood deaths than any other vaccine-preventable disease, and it's also one of the most infectious viruses known," says Saphire.

It's not just young children at risk, explains Zyla. "The current vaccine works well, but it cannot be taken by pregnant people or people with compromised immune systems," Zyla says.

There is no specific treatment for measles, so researchers are looking for antibodies to use as an emergency treatment to prevent severe disease.

To better understand how the measles virus fuses with cells, the LJI team turned to an antibody called mAb 77. Researchers have found that mAb 77 targets the measles fusion glycoprotein, the piece of viral machinery measles uses to enter human cells via a specialized process called fusion.

Could mAb 77 work as a therapeutic antibody against measles? To find out, the LJI scientists investigated exactly how the antibody combats the virus.

Membrane fusion, interrupted

The LJI team needed to engineer a version of the measles fusion glycoprotein—a harmless fragment of the virus—stable enough to image with a cryo-electron microscope. To do this, Zyla worked closely with scientists in Porotto's laboratory at Columbia University.

Porotto's group had uncovered some strange mutations in a measles variant that attacked peoples’ central nervous systems. This mutated variant had some weak points in its fusion glycoprotein structure. To compensate, the virus had evolved special stabilizing mutations. "The virus has to mutate to go into the brain, but then it needs these stabilizing mutations to compensate," says Porotto.

Thanks to these discoveries at Columbia, Zyla had a handy blueprint for engineering a fusion glycoprotein with these same stabilizing mutations. This new fusion glycoprotein could be mass produced in cell culture, and it was sturdy enough for structural investigations.

"We got extremely good yields for the glycoprotein, which also enabled us to do structural biology and biochemical and biophysical studies," says Zyla.

Next, the researchers started capturing images with the help of the LJI Cryoelectron Microscopy Core. The new images showed the fusion glycoprotein together "in complex" with mAb 77.

The researchers found mAb 77 arrests the virus in the middle of the fusion process—when fusion glycoprotein is already part way done "folding" into the right conformation to complete membrane fusion. At last, the researchers could see exactly how mAb 77 locks together pieces of the fusion glycoprotein to prevent viral infection.

"It was striking to see what this intermediate step in the fusion process actually looks like," says Zyla.

Next steps for stopping measles

Now that they know how mAb 77 works, the researchers hope the antibody could be used as part of a treatment cocktail to protect people against measles or to treat people with active measles infection.

In a follow-up experiment, the researchers showed that mAb 77 provided significant protection against measles in cotton rat models of measles virus infection. Cotton rats pretreated with mAb 77 prior to measles virus exposure showed either no infection or reduced signs of infection in their lung tissue.

Going forward, Saphire and Zyla are interested in studying different antibodies against measles. "We'd like to stop fusion at different points in the process and investigate other therapeutic opportunities," Zyla says.

Zyla also plans to continue working closely with measles researchers at Columbia University. "The combination of structural biology expertise from LJI and cell biology and virology expertise from Columbia was key to pushing this project forward," says Zyla.

Additional authors of the study, "A neutralizing antibody prevents post-fusion transition of measles virus fusion protein," include Roberta Della Marca, Gele Niemeyer, Gillian Zipursky, Kyle Stearns, Cameron Leedale, Elizabeth B. Sobolik, Heather M. Callaway, Chitra Hariharan, Weiwei Peng, Diptiben Parekh, Tara C. Marcink, Ruben Diaz Avalos, Branka Horvat, Cyrille Mathieu, Joost Snijder, Alexander L. Greninger, Kathryn M. Hastie, Stefan Niewiesk, and Anne Moscona.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NS105699, NS091263, and AI176833), Swiss National Science Foundation Postdoc Mobility fellowships (P2EZP3_195680 and P500PB_210992), the Measles Virus Biobank, the Dutch Research Council NWO Gravitation 2013 BOO, Institute for Chemical Immunology (ICI 024.002.009), and institutional funds of La Jolla Institute for Immunology (EOS)

END

A promising weapon against measles

Researchers at LJI and Columbia University uncover exactly how a neutralizing antibody blocks measles virus infection

2024-06-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The most obese children with dengue are more than twice as likely as others to be hospitalized with dengue, according to study of 4,782 10- to 18-year-olds in Sri Lanka

2024-06-27

The most obese children with dengue are more than twice as likely as others to be hospitalized with dengue, according to study of 4,782 10- to 18-year-olds in Sri Lanka.

####

Article URL: http://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0012248

Article Title: Is the rise in childhood obesity rates leading to an increase in hospitalizations due to dengue?

Author Countries: Sri Lanka, United Kingdom

Funding: This study has been supported by the World Health Organization Unity Studies (GNM and CJ), a global sero-epidemiological standardization initiative, with funding to the World Health Organization and the UK Medical Research Council (GSO). The World Health Organization ...

Prehistoric Pompeii discovered: Most pristine trilobite fossils ever found shake up scientific understanding of the long extinct group

2024-06-27

Researchers have described some of the best-preserved three-dimensional trilobite fossils ever discovered. The fossils, which are more than 500 million years old, were collected in the High Atlas of Morocco and are being referred to by scientists as “Pompeii” trilobites due to their remarkable preservation in ash.

The trilobites, from the Cambrian period, have been the subject of research by an international team of scientists, led by Prof Abderrazak El Albani, a geologist based at University of Poitiers and originally from Morocco. The team included Dr Greg Edgecombe, a palaeontologist ...

Scientists use computational modeling to guide a difficult chemical synthesis

2024-06-27

CAMBRIDGE, MA — Researchers from MIT and the University of Michigan have discovered a new way to drive chemical reactions that could generate a wide variety of compounds with desirable pharmaceutical properties.

These compounds, known as azetidines, are characterized by four-membered rings that include nitrogen. Azetidines have traditionally been much more difficult to synthesize than five-membered nitrogen-containing rings, which are found in many FDA-approved drugs.

The reaction that the researchers used to create azetidines is driven by a photocatalyst that excites the molecules from their ground energy state. Using computational models that they developed, the researchers ...

The worm has turned: DIY lab platform evaluates new molecules in minutes

2024-06-27

Plants are powerhouses of molecular manufacturing. Over the eons, they have evolved to produce a plethora of small molecules — some are beneficial and valuable to humans, others can be deadly. For years, a good way for scientists looking for new medicines to distinguish beneficial plant-derived molecules from harmful ones has been through a scientific sniff test — dab a bit of the molecule at one end of a petri dish and drop tiny nematode worms (C. elegans) at the other, then wait to see if the chemically sensitive worms move toward or away from the compound in question, a process known as chemotaxis.

This “artisanal” ...

Under pressure: How comb jellies have adapted to life at the bottom of the ocean

2024-06-27

The bottom of the ocean is not hospitable: there is no light; the temperature is freezing cold; and the pressure of all the water above will literally crush you. The animals that live at this depth have developed biophysical adaptations that allow them to survive in these harsh conditions. What are these adaptations and how did they develop?

University of California San Diego Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Itay Budin teamed up with researchers from around the country to study the cell membranes of ctenophores (“comb jellies”) and found they had unique lipid structures that allow them to live under intense pressure. Their work appears in Science.

Adapting ...

A CHARMed collaboration created a potent therapy candidate for fatal prion diseases

2024-06-27

EMBARGOED UNTIL 27-Jun-2024 14:00 ET

Drug development is typically slow: the pipeline from basic research discoveries that provide the basis for a new drug to clinical trials to production of a widely available medicine can take decades. But decades can feel impossibly far off to someone who currently has a fatal disease. Broad Institute Senior Group Leader Sonia Vallabh is acutely aware of that race against time, because the topic of her research is a neurodegenerative and ultimately fatal disease–fatal familial insomnia, a type of prion disease–that she will almost certainly develop as she ages. Vallabh and her husband, Eric Minikel, switched careers ...

Researchers find flexible solution for separating gases

2024-06-27

For a broad range of industries, separating gases is an important part of both process and product—from separating nitrogen and oxygen from air for medical purposes to separating carbon dioxide from other gases in the process of carbon capture or removing impurities from natural gas.

Separating gases, however, can be both energy-intensive and expensive. “For example, when separating oxygen and nitrogen, you need to cool the air to very low temperatures until they liquefy. Then, by slowly increasing the temperature, the gases will evaporate at different points, allowing one to become a gas again and separate out,” explains Wei Zhang, a University of Colorado Boulder professor ...

Pacific cod can’t rely on coastal safe havens for protection during marine heat waves, OSU study finds

2024-06-27

During recent periods of unusually warm water in the Gulf of Alaska, young Pacific cod in near shore safe havens where they typically spend their adolescence did not experience the protective effects those areas typically provide, a new Oregon State University study found.

Instead, during marine heat waves in 2014-16 and 2019, young cod in these near shore “nurseries” around Kodiak Island in Alaska experienced significant changes in their abundance, growth rates and diet, with researchers estimating that only the largest 15-25% of the island’s cod population survived the summer. Even after the high temperatures subsided, the ...

Bird flu stays stable on milking equipment for at least one hour

2024-06-27

Bird flu, or H5N1 virus, in unpasteurized milk is stable on metal and rubber components of commercial milking equipment for at least one hour, increasing its potential to infect people and other animals, report researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Emory University in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The study underscores the heightened risk of bird flu exposure for dairy farm workers and signals the need for wider adoption of personal protective equipment, including face shields, masks and eye protection.

“Dairy cows have to be milked even if they are sick, and it has not been clear for how long the virus contained in residual milk from the ...

Printed sensors in soil could help farmers improve crop yields and save money

2024-06-27

MADISON — University of Wisconsin–Madison engineers have developed low-cost sensors that allow for real-time, continuous monitoring of nitrate in soil types that are common in Wisconsin. These printed electrochemical sensors could enable farmers to make better informed nutrient management decisions and reap economic benefits.

“Our sensors could give farmers a greater understanding of the nutrient profile of their soil and how much nitrate is available for the plants, helping them to make more precise decisions on how much fertilizer they really need,” says Joseph Andrews, an assistant professor of mechanical ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

Rediscovered music may never sound the same twice, according to new Surrey study

Ochsner Baton Rouge expands specialty physicians and providers at area clinics and O’Neal hospital

New strategies aim at HIV’s last strongholds

Ambitious climate policy ensures reduction of CO2 emissions

Frontiers in Science Deep Dive webinar series: How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

UMaine researcher develops model to protect freshwater fish worldwide from extinction

Illinois and UChicago physicists develop a new method to measure the expansion rate of the universe

Pathway to residency program helps kids and the pediatrician shortage

How the color of a theater affects sound perception

Ensuring smartphones have not been tampered with

Overdiagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer

Association of dual eligibility and medicare type with quality of postacute care after stroke

Shine a light, build a crystal

AI-powered platform accelerates discovery of new mRNA delivery materials

Quantum effect could power the next generation of battery-free devices

New research finds heart health benefits in combining mango and avocado daily

New research finds peanut butter consumption builds muscle power in older adults

Study identifies aging-associated mitochondrial circular RNAs

The brain’s primitive ‘fear center’ is actually a sophisticated mediator

Brain Healthy Campus Collaborative announces winner of first-ever Brain Health Prize

Tokyo Bay’s night lights reveal hidden boundaries between species

As worms and jellyfish wriggle, new AI tools track their neurons

[Press-News.org] A promising weapon against measlesResearchers at LJI and Columbia University uncover exactly how a neutralizing antibody blocks measles virus infection