(Press-News.org) New UCSF study shows that suppressing a protein turns ordinary fat into a calorie burner and may explain why drug trials attempting the feat haven’t been successful.

Researchers at UC San Francisco have figured out how to turn ordinary white fat cells, which store calories, into beige fat cells that burn calories to maintain body temperature.

The discovery could open the door to developing a new class of weight-loss drugs and may explain why clinical trials of related therapies have not been successful.

Until now, researchers believed creating beige fat might require starting from stem cells. The new study published July 1 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, showed that ordinary white fat cells can be converted into beige fat simply by limiting production of a protein.

“A lot of people thought this wasn’t feasible,” said Brian Feldman, MD, PhD, the Walter L. Miller, MD Distinguished Professor in Pediatric Endocrinology and senior author of the study. “We showed not only that this approach works to turn these white fat cells into beige ones, but also that the bar to doing so isn’t as high as we’d thought.”

A fat transformation

Many mammals have three “shades” of fat cells: white, brown and beige. White fat serves as energy reserves for the body, while brown fat cells burn energy to release heat, which helps maintain body temperature.

Beige fat cells combine these characteristics. They burn energy, and unlike brown fat cells, which grow in clusters, beige fat cells are embedded throughout white fat deposits.

Humans and many other mammals are born with brown fat deposits that help them maintain body temperature after birth. But, while a human baby’s brown fat disappears in the first year of life, beige fat persists.

Humans can naturally turn white fat cells into beige ones in response to diet or a cold environment. Scientists tried to mimic this by coaxing stem cells into becoming mature beige fat cells.

But stem cells are rare, and Feldman wanted to find a switch he could flip to turn white fat cells directly into beige ones.

“For most of us, white fat cells are not rare and we’re happy to part with some of them,” he said.

Of mice and humans

Feldman knew from his earlier experiments that a protein called KLF-15 plays a role in metabolism and the function of fat cells.

With postdoctoral scholar Liang Li, PhD, Feldman decided to investigate how the protein functioned in mice, which retain brown fat throughout their lives. They found that KLF-15 was much less abundant in white fat cells than in brown or beige fat cells.

When they then bred mice with white fat cells that lacked KLF-15, the mice converted them from white to beige. Not only could the fat cells switch from one form into another, but without the protein, the default setting appeared to be beige.

The researchers then looked at how KLF-15 exerts this influence. They cultured human fat cells and found that the protein controls the abundance of a receptor called Adrb1, which helps maintain energy balance.

Scientists knew that stimulating a related receptor, Adrb3, caused mice to lose weight. But human trials of drugs that act on this receptor have had disappointing results.

A different drug targeting the Adrb1 receptor in humans is more likely to work, according to Feldman, and it could have significant advantages over the new, injectable weight-loss drugs that are aimed at suppressing appetite and blood sugar.

Feldman's approach might avoid side effects like nausea because its activity would be limited to fat deposits, rather than affecting the brain. And the effects would be long lasting, because fat cells are relatively long-lived.

“We’re certainly not at the finish line, but we’re close enough that you can clearly see how these discoveries could have a big impact on treating obesity,” he said.

Authors: Liang Li is also an author of this study.

Funding: This work was funded by NIH grant R01DK132404.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

###

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

END

Scientists turn white fat cells into calorie-burning beige fat

2024-07-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How politicizing migration harms health

2024-07-01

Politicians around the world are increasingly mobilizing anti-immigrant sentiment to garner support and votes—a trend that is especially evident as the US presidential election approaches.

While political rhetoric that stereotypes and scapegoats immigrants is well-documented, less attention has been given to the impact of these sentiments on immigrants themselves. In an article published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and in a recently published book, Migration Stigma (MIT Press), scholars identify “migration ...

Excess US deaths attributable to high all-cause mortality rates among youths

2024-07-01

About The Study: The mortality gap between the U.S. and comparison countries widened in the last decade. Each year, nearly 20,000 deaths among youths ages 0 to 19 years would not have occurred had U.S. youths experienced the median mortality rates of 16 comparison countries. More than half of these deaths involved infants, reflecting disproportionately high U.S. infant mortality rates.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Steven H. Woolf, M.D., M.P.H., email steven.woolf@vcuhealth.org.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.1869)

Editor’s ...

COVID-19 vaccination in the first trimester and major structural birth defects among live births

2024-07-01

About The Study: Among live-born infants, first-trimester mRNA COVID-19 vaccine exposure was not associated with an increased risk for selected major structural birth defects in this multisite cohort study.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Elyse O. Kharbanda, M.D., M.P.H., email elyse.o.kharbanda@healthpartners.com.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.1917)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional ...

Dehumanizing rhetoric on immigration harms public health

2024-07-01

With Donald Trump and other right-wing politicians increasingly using dehumanizing rhetoric to stigmatize immigrants coming to our nation's borders, doctors and other health officials should prepare for the resulting health consequences.

Such is the message of a “Viewpoint” article co-authored by UC Riverside professor Bruce Link and published Monday, July 1, in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Link and his co-authors quote Trump as saying, “No, they’re not humans. They’re not humans. They’re ...

A prosthesis driven by the nervous system helps people with amputation walk naturally

2024-07-01

State-of-the-art prosthetic limbs can help people with amputations achieve a natural walking gait, but they don’t give the user full neural control over the limb. Instead, they rely on robotic sensors and controllers that move the limb using predefined gait algorithms.

Using a new type of surgical intervention and neuroprosthetic interface, MIT researchers, in collaboration with colleagues from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, have shown that a natural walking gait is achievable using a prosthetic leg fully driven by the body’s own nervous system. ...

Novel blood test helps improve cancer treatments

2024-07-01

The earlier a cancer is detected, the better the chances that treatment will be effective. This applies to almost all types of cancer. Another crucial element in successfully treating patients is to individually assess the benefits and risks of individual forms of therapy and to regularly monitor treatment success. To do this, oncologists have a range of methods at their disposal, most notably imaging technology and invasive measures such as tissue biopsies, punctures and endoscopic procedures.

Analyzing gene fragments in the bloodstream

Researchers ...

Research-driven Korea University College of Medicine promotes joint research with global scholars

2024-07-01

Korea University's College of Medicine (Dean Pyun, Sung Bom) hosted the 1st Research Nexus Program in order to enhance international research network cooperation and vitalize global joint research.

This program shares the latest research trends and aims to invigorate international joint research by opening a seminar inviting top global scholars to promote international research performances.

The 1st program held an invitation seminar of Prof. Jeffrey D. Macklis, the "global authority in the field of neurogenesis" (Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University).

Prof. Macklis ...

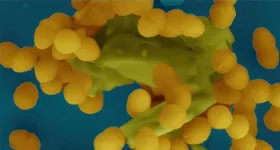

Degradation of cell wall key in the spread of resistance

2024-07-01

A study at Umeå University, Sweden, provides new clues in the understanding of how antibiotic resistance spreads. The study shows how an enzyme breaks down the bacteria's protective outer layer, the cell wall, and thus facilitates the transfer of genes for resistance to antibiotics.

"You could say that we are adding a piece of the puzzle to the understanding of how antibiotic resistance spreads between bacteria," says Ronnie Berntsson, Associate Professor at Umeå University and one of the authors behind the study.

The Umeå researchers have studied Enterococcus faecalis, which is a bacterium that often ...

The evidence is mounting: humans were responsible for the extinction of large mammals

2024-07-01

The debate has raged for decades: Was it humans or climate change that led to the extinction of many species of large mammals, birds, and reptiles that have disappeared from Earth over the past 50,000 years?

By "large," we mean animals that weighed at least 45 kilograms – known as megafauna. At least 161 species of mammals were driven to extinction during this period. This number is based on the remains found so far.

The largest of them were hit the hardest – land-dwelling herbivores weighing over a ton, the megaherbivores. Fifty thousand years ago, there were 57 species of megaherbivores. Today, only 11 remain. These remaining ...

Common respiratory infections may have protected children from COVID-19, study suggests

2024-07-01

Analyzing nasal swabs taken during the pandemic, researchers at Yale School of Medicine suggest that the frequent presence of other viruses and bacteria may have helped to protect children from the worst effects of COVID-19 by boosting their immune systems. Their results will be published July 1 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM).

Children are generally more susceptible than adults to respiratory infections such as the common cold, and yet, for unknown reasons, the SARS-CoV-2 virus tends to cause less severe ...