(Press-News.org) An invasive fungus that colonizes the skin of hibernating bats with deadly consequences is a stealthy invader that uses multiple strategies to slip into the small mammals' skin cells and quietly manipulate them to aid its own survival. The fungus, which causes the disease white-nose syndrome, has devastated several North American species over the last 18 years.

Scientists have learned much about the fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, since it was first documented in a New York cave in 2006, including where it thrives, its distribution, and clinical features. But exactly how the fungus initiates its infection has remained a "black box — a big mystery," says Bruce Klein, a professor of pediatrics, medicine and medical microbiology and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

That dearth of understanding has made it challenging to develop countermeasures to treat or prevent infections.

Now, Klein and Marcos Isidoro-Ayza, a PhD candidate at Klein's lab, have for the first time been able to study in detail how the fungus gains entry and covertly hijacks cells called keratinocytes at the surface of bats' skin.

The feat is detailed in the July 12, 2024, issue of Science.

The researchers found that P. destructans uses infected cells as a refuge and prevents the cells from dying, which in turn thwarts the bats' immune system and allows the microbial invader to continue growing and slip into more cells.

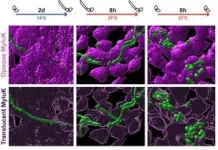

To do so, Klein and Isidoro-Ayza created the first-ever keratinocyte cell line from the skin of a little brown bat. Further, they successfully mimicked the conditions of hibernation, which are marked by wide body temperature fluctuations that accompany periods of torpor — when the animals’ metabolism slows and body temperature drops — and arousal.

This is crucial to understanding P. destructans infections because the cold-loving fungus gains its foothold during the chilly conditions of torpor and is able to persist during arousal, when the bats’ body temperature increases.

Klein and Isidoro-Ayza have already identified how the fungus gains its stealth entry into cells: by co-opting a protein on their surface called epidermal growth factor receptor, or EGFR. Mutations in the same receptor in human cells drive certain lung cancers and these cancers are treated with an existing drug called gefitinib, opening the possibility it could be used to treat or prevent white-nose syndrome.

"Remarkably, when we inhibited the receptor with this drug, we stopped the infection," says Isidoro-Ayza. "This is an FDA-approved drug that could potentially be used in the future for the treatment of susceptible bat species."

While EGFR's precise role in infection is not yet completely clear, Klein and Isidoro-Ayza have learned much about how the fungus works.

Its initial entry occurs during torpor, when bats' immune systems are dormant and their body temperature is in an ideal range for P. destructans to germinate and grow. During torpor, the fungus penetrates bats' skin cells with its hyphae — slender filaments through which it grows and gathers nutrients — without breaking the cells' membranes. Doing so would trigger the cells' death and expose the fungus to the bats’ immune system.

Klein and Isidoro-Ayza also found that the fungus employs multiple strategies that allow it to continue its invasion during periods of arousal, despite the bats' higher body temperatures and reactivated immune system.

First, during arousal periods, the fungus manipulates the cells so they engulf the fungus in a process known as endocytosis, rather than the fungus using its hyphae to penetrate the cell.

Second, they found that the fungus spores — microscopic particles by which it reproduces — are coated in a layer of melanin that protects them from the cells' strategies for killing invading microbes.

"That allows the spore to survive that period of arousal, and when the bat goes back into torpor, the spores inside of its cells start germinating again and keep colonizing the skin," explains Isidoro-Ayza, who is a student in the UW–Madison School of Veterinary Medicine’s comparative biomedical sciences graduate program.

P. destructans' final infection strategy is to block apoptosis, also known as programmed cell death, which is a defense mechanism cells use to expose pathogens so immune cells can root them out and destroy them.

"By not killing the cells, the fungus can linger in the tissue and go into deeper layers of the skin," says Isidoro-Ayza.

With this new knowledge in hand, the researchers are hopeful that treatments and a potential vaccine are closer to becoming reality.

These findings are just one product of a collaboration between Klein and Isidoro-Ayza and scientists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center in Madison. The effort received $2 million in funding from the National Science Foundation and Paul G. Allen Family Foundation in 2023 to search for better insight into how P. destructans causes infection and develop treatment and prevention strategies against white-nose syndrome.

The research is valuable not only for the conservation of bats, which provide a number of benefits including as pollinators and insect predators, but because fungal pathogens are a growing problem for many species.

"There are fungal diseases causing epidemics and pandemics in different types of organisms, including plants, invertebrate animals, amphibians, reptiles and bats," says Isidoro-Ayza. So, any mechanism that we discover or better understand in this disease could have implications for the conservation of other species too."

This research was supported by funding from The U.S. Geological Survey (G20AC00050), the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (13190304), the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (MSN247980), the National Science Foundation (2301729), La Caixa Foundation fellowship (ID 100010434) under agreement LCF/BQ/AA17/11610020, National Institutes of Health (T32OD010423) and the Morris Animal Foundation (D23ZO-461).

# # #

--Will Cushman, wcushman@wisc.edu, 608-286-1986

END

According to current understanding, menstrual cramps only happen in cycles in which an egg is released, or an ovulatory cycle. But new research from the University of British Columbia (UBC) is challenging this notion.

The findings, published in the Journal of Pain Research, reveal that some women not only experience cramps when no egg is released, but that cramps can be more severe and last longer during these anovulatory cycles.

“I was surprised to see significant cramps in menstrual cycles with or without ovulation, which challenges current thinking” said co-author, Dr. Paul Yong, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UBC and Canada Research ...

Racial disparities in dementia are due to social determinants of health, with genetic ancestry playing no role, according to a new study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The study, which was based on a long-running population-based survey in four Latin American countries, helps explain why people of predominantly Native American or African ancestry have a higher prevalence of dementia: Study participants were more likely to experience social contexts and health conditions that raised their risk of cognitive decline, such as lower education levels, rural residency and high blood pressure. Once such factors ...

HOUSTON – (July 11, 2024) – Implantable technologies have significantly improved our ability to study and even modulate the activity of neurons in the brain, but neurons in the spinal cord are harder to study in action.

“If we understood exactly how neurons in the spinal cord process sensation and control movement, we could develop better treatments for spinal cord disease and injury,” said Yu Wu, a research scientist who is part of a team of Rice University neuroengineers working on a solution to this problem.

“We developed a tiny sensor, spinalNET, that records the electrical activity of spinal neurons as the subject performs normal ...

Image

The flow of water within a muscle fiber may dictate how quickly muscle can contract, according to a University of Michigan study.

Nearly all animals use muscle to move, and it's been known for a long time that muscle, like all other cells, is composed of about 70% water. But researchers don't know what sets the range and upper limits of muscle performance. Previous research into how muscle works focused only on how it worked on a molecular level rather than how muscle fibers are shaped, that they are three-dimensional ...

Nearly one in 10 people who get COVID while pregnant will go on to develop long COVID, a report publishing July 11th in Obstetrics & Gynecology has found.

“It was surprising to me that the prevalence was that high,” says Torri Metz, MD, vice chair of research of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Utah Health, who co-led the nationwide study. “This is something that does continue to affect otherwise reasonably healthy and young populations.”

Intersecting risks

Prior research had shown that COVID affects pregnant people in uniquely ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — The rabbit hole contains madness, according to author Lewis Carroll. Online, that madness manifests in the form of increasingly extreme content, often without users realizing it. A new study by Penn State researchers suggests that giving users control over the interface feature of autoplay can help them realize that they are going down a rabbit hole.

The work — which the researchers said has implications for responsibly designing online content viewing platforms and algorithms, as well as helping users better ...

VIDEO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6j4zjqI21Gs

Faculty in UCF’s College of Sciences and College of Engineering and Computer Science are preparing incoming students to keep pace with the emerging multidisciplinary field of artificial intelligence.

A team of five faculty, led by UCF’s Center for Research in Computer Vision (CRCV), recently received a U.S. National Science Foundation grant totaling nearly $2.5 million over five years to serve as resources to uplift bright yet low-income or struggling ...

One of the intriguing abilities of the human mind is daydreaming, where the mind wanders off into spontaneous thoughts, fantasies and scenarios, often without conscious effort, allowing creativity and reflection to flow freely.

In a new study published in Frontiers of Human Neuroscience, University of Arizona researchers used low-intensity ultrasound technology to noninvasively alter a brain region associated with activities such as daydreaming, recalling memories and envisioning the future. They found that the technique can ultimately enhance mindfulness, marking a major advancement in the field ...

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Gravitational Waves, ripples in space-time predicted by Einstein almost a century ago, were detected for the first time in 2015. A new study led by Yanou Cui, an associate professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Riverside, reports that very simple forms of matter could create detectable gravitational wave backgrounds soon after the Big Bang.

“This mechanism of creating detectable gravitational wave backgrounds may shed light on ...

Employers and recruiting firms frequently infuse job postings with words and phrases like “ambitious,” “thinks outside the box,” “communicates persuasively” and “thinks strategically.”

However, according to a forthcoming Management Science study, such keywords signify “rule-bender” (versus “rule-follower”) language and heavily draw narcissistic applicants who are more likely to engage in unethical or fraudulent behavior–significantly ...